South Carolina Punished a Black Woman for Protesting. Her Supporters Demand Her Release.

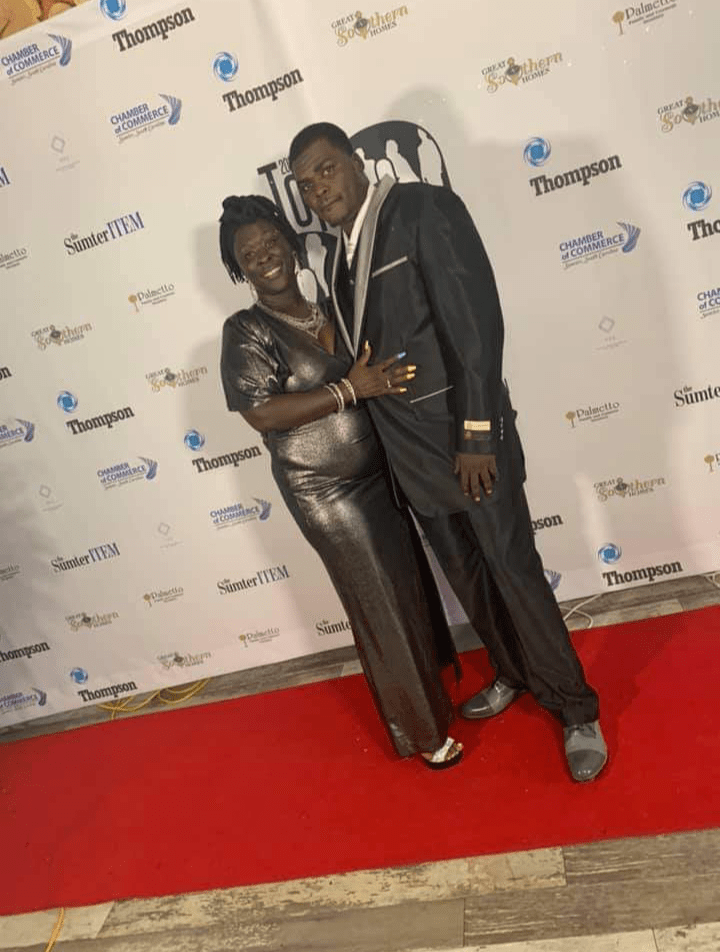

The moment Eric Kennedy laid eyes on Brittany Martin a decade ago, he knew she was the woman he wanted to share the rest of his life with. From the rich tones of her melanated skin to her unwavering pride for being a Black woman and mother, Kennedy’s admiration of Martin has been unconditional, even as he says she is wrongly serving four years in prison for talking back to police officers during a protest.

Their whirlwind romance included Kennedy becoming a father to Martin’s three living children and adding two more boys to their household in Waterloo, Iowa. A year before George Floyd was killed, Kennedy and Martin moved their budding family to Sumter, South Carolina, where Kennedy grew up.

By that time, Kennedy and Martin were fed up with the number of Black people killed by police – and Floyd’s murder heightened their commitment to justice. The couple turned their concerns about protecting and raising Black children into action. They launched Mixed Sistaz United, a grassroots organization that aims to unify and support the community by feeding the unhoused and hosting events such as voter registration drives and demonstrations in light of police violence in Sumter and around the country. Sumter County’s population of 104,000 is almost evenly divided between Black and white people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Martin, like thousands of protesters in the summer of 2020, took to the streets demanding more police accountability. With bullhorns, organizers shouted: “No justice, no peace” and “Black lives matter.” At the height of the demonstrations in Sumter and across the country, protesters were arrested. Martin was arrested on charges of instigating a riot and five counts of threatening the lives of those police officers on June 4 and released 27 days later. That same day, a warrant was issued for Martin’s arrest after a grand jury indicted her. She was released on bond.

Yet, as other arrested protesters’ cases were dismissed nationwide or not prosecuted at all, including Kennedy’s, Martin endured nearly two years of pre-trial litigation. Months before she was convicted and sentenced on May 16, 2022, for breaching the peace in a high and aggravated manner, she mourned the murder of her 18-year-old son.

As many of those wrongful arrests resulted in millions of dollars in lawsuit settlements to be divided, Martin remains in prison 22 months later. She tells Capital B on a call from Logan Correctional Facility in Lincoln, Illinois — a prison she was transported to without her family or attorney being notified — that she has experienced unthinkable atrocities while praying for an appellate court to exonerate her.

Martin’s case wasn’t the first breaching the peace at a high and aggravated manner conviction in South Carolina’s criminal justice history. Yet, it is another example of how prosecutors can play with legal terms and phrases within already existing statutes to prosecute the law.

Martin’s punishment has been viewed as a message to other Black people in the state to think twice before being strong and unapologetically Black while exercising their constitutional right to freedom of speech, advocates said. She may be the only known leader of protests during the civil unrest of 2020 — and perhaps in the state’s history — who was sent to prison without laying a finger on a police officer or damaging property.

As the holidays approached in November 2022, Martin gave birth to her sixth child in the waiting room of a South Carolina hospital while in the custody of the state’s Department of Corrections and without assistance from her doula.

“What I am asking for the public, from God’s people, is to help me survive this,” Martin said.

“Give that same energy that I was given when I was out there. The same love, candor and care … is what I need for my life to be saved so that I can come out and celebrate that moment with everyone, of my exoneration.”

She said she is expected to be released in March 2025.

Persecuted for being “unapologetically Black”?

Police said Martin was the mastermind behind a group of organizers who joined four consecutive days of protests that were already in progress, “to incite unrest, violence against law enforcement officers and destruction of public and private property,” WACH reported.

During Martin’s trial, the jurors viewed a nearly 14-minute reel of edited police body camera footage between May 31 and June 3, 2020. Capital B reviewed the footage as well. It does show Martin and several others joining what seems to be other peaceful protesters. And on June 3, 2020, the date stamped on the video, Martin does tell an officer that she is “the one holding the protest” that day.

Each group had a vastly different style of protesting, yet they were both nonviolent. Some protesters held signs, recited chants, and, on June 2, 2020, conducted a reception line of hugs from crying children and women of all ages for the police officers who were on duty overseeing the protests. Simultaneously, when Sumter police attempted to give Martin and seven members of her group a checklist of how they were to protest, some, including Martin, spewed harsh- and profanity-riddled sentences in exchange.

For Kennedy, 38, and Martin, 36, their side-eye toward law enforcement and the criminal justice system began long before 2020.

Kennedy said his uncle was wrongly convicted of rape and died in prison before DNA cleared his name. His father was thrown in jail for not paying child support, but was a consistent presence in his home. And Martin’s relative was killed in 2016 by Sumter police — the first of five people killed by law enforcement in the county, according to the Mapping Police Violence database.

However, Martin’s actions on June 3, 2020, were no different from other protesters who were reaching their boiling points with police-sanctioned violence.

As Martin’s group arrived at the Sumter Police Department, a high-ranking officer gave them instructions on where they could protest. Police said Martin “became upset” with the officer after he said “what you do from that point will dictate what we do,” according to an incident report and the police body camera footage.

Martin, who stands all of 5 feet, 3 inches tall, replied while pointing her index finger at the five Sumter police officers:

“You can’t tell us how to fucking protest.”

“Go call all our hitters now, you tell them get ready, everybody is strapped, everybody. Y’all better be ready, those vests ain’t gonna save you. Some of us gonna be hurt, but some of y’all going to be hurt. We are ready to die for this, we are tired of it. You better be ready to die for the blue; I am ready to die for the Black. I am dying for the Black. You better be ready to die for the blue.”

She was arrested on June 4, 2020.

“Ms. Martin is an unapologetically Black woman. You don’t have to agree with how she is to agree that she should have a right to free speech,” Sybil D. Rosado, Martin’s trial attorney, said.

A jury acquitted Martin of a laundry list of violent offenses that included instigating a riot and five counts of threatening the lives of those police officers. Instead, Martin was convicted of a charge that was added by the grand jury: breaching the peace in a high and aggravated manner.

With this felony conviction, Martin has been placed among thousands of other incarcerated Black women and girls, who have been ripped away from their families for excessive amounts of time.

“It boggles the mind and it’s frightening” that the law can be used against someone for speaking their mind during a protest, Rosado told Capital B.

As a college student, Rosado said she said worse to the police while protesting against apartheid in South Africa. Some of Rosado’s University of Florida classmates were arrested, but no one gained a criminal record or was sent to prison for four years, Rosado said.

An “egregious” conviction and allegations of bias

Martin’s arrest, conviction, and incarceration have sparked outrage from abolitionists and civil rights advocates.

The South Carolina chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union joined with Rosado and filed an appeal in April 2023 to get Martin’s “egregious” conviction thrown out, Meredith McPhail, Martin’s appellate attorney, said. The nonprofit organization typically handles civil rights cases but chose to take on Martin’s criminal appeal.

McPhail said that the crime Martin was convicted of is a common law crime, which means it is not written in statute but rather is established by legal precedent. Brittany and her legal team argue that breach of the peace of a high and aggravated nature is an unconstitutionally vague offense.

“Breaching the peace” and “high and aggravated manner” together does not specify what particular conduct violates peacefulness and to what degree.

“With this kind of vagueness in criminal laws, [it] leads to arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement. That is exactly what we’re seeing in Ms. Martin’s case,” McPhail said.

In the prosecutors’ response to Martin’s appeal, they revealed “exactly why Sumter County officials prosecuted Ms. Martin: because she was not ‘polite’ and because she ‘attempted to spread’ ideas they disagree with,” McPhail wrote in their final reply that was filed in October.

Read More: Recent Rise in Women and Girls Behind Bars Is Rooted in the War on Drugs

Andrea James, the founder of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls, said Martin’s conviction is another example of racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

“There’s so much in Brittany’s case that needs to be brought forward to the public’s attention. Unfortunately, the laundry list of degradations Brittany [experienced] … is what’s happening to women, Black women, in these prisons every day” and mirrors how Black women were treated during slavery, James said.

In 2010, James, along with other incarcerated Black women in a Danbury, Connecticut, federal prison, started the National Council. Five years ago, the organization set a goal to end the incarceration of women and girls by appealing to presidents, governors, and parole boards to grant clemency or commute the sentences of potentially hundreds based on their overall lived experiences and health.

James, along with the National Council’s local partners in Illinois, have pledged to support Martin and will include her name on posters for their 10th FreeHer March and Rally in Washington, D.C., next month.

Additionally, Black Lives Matter Grassroots launched an online campaign that demands South Carolina’s Gov. Henry McMaster immediately pardon Martin.

It is outrageous that “the violent, murderous behavior of white men who stormed the Capitol” didn’t receive similar treatment, James said.

“They did me so wrong”

Shortly after their newborn daughter, Blessing, was handed over to Kennedy, Martin said her life behind bars became increasingly dangerous.

From the moment she was sent to prison, she said she repeatedly pushed back against having her locs cut. The stress of the demands from prison guards complicated her pregnancy. As a result, she was hit with several infractions that added extra time to her sentence, deducted good-time credits and suspended her phone privileges for months, according to copies of Martin’s records that were provided to Capital B.

After recovering from childbirth, Martin’s interactions with prison guards about her refusal to cut off her natural hair turned violent. Martin’s fight about her hair was not based on vanity. A loc from her deceased son was blended into hers. Her desperation to hold onto her son’s memory would often turn into failed negotiations with prison officials to get placed into solitary confinement instead. She begged and pleaded until one day her hair was cut off while she was “chained down.”

A spokeswoman for the state’s Department of Corrections said Martin’s hair was in violation of its policy, despite the hairstyle’s religious and cultural significance. Martin is a Black Hebrew Israelite, Kennedy said.

“They did me so wrong,” Martin said.

After that ordeal, Rosado made a trip to the women’s prison in Columbia, South Carolina, to document what happened — but Martin was gone. Martin said after she was sexually assaulted and beaten by prison guards, she was secretly transferred nearly 900 miles away to the prison in Illinois.

“Any accusations Martin made while incarcerated were investigated. All were determined to be unfounded,” Chrysti Shain, director of communications for the state’s Department of Corrections, wrote in an email.

There is a notation without further details of “sexual misconduct” that occurred on July 21, 2023, according to Martin’s disciplinary sanctions records. The last recorded action in Martin’s detailed report was in September 2023. She cannot be found on Illinois’ online prison records.

This move was “part of the Interstate Corrections Compact, which is a national agreement between states to house inmates in the situation best suited for them to spend their time,” Shain wrote.

To James, this action by the prison officials is another form of legalized slavery.

It took nearly two weeks for Kennedy and Rosado to locate Martin. And as soon as she was found, Kennedy packed up the kids and moved to Illinois. Having their children nearby would give Martin some ease, he said.

“I bow in grace to the single mothers out there,” Kennedy told Capital B. “This has been a tough almost two years for me. I’m now a single father of five children with five different personalities.”

Kennedy and the children will have to wait a year to be reunited with their matriarch.

“We all miss her. She needs to be home with her family.”

This story has been updated.

The post South Carolina Punished a Black Woman for Protesting. Her Supporters Demand Her Release. appeared first on Capital B News.