My Son May Be Gone, But I'll Always Be a Caregiver

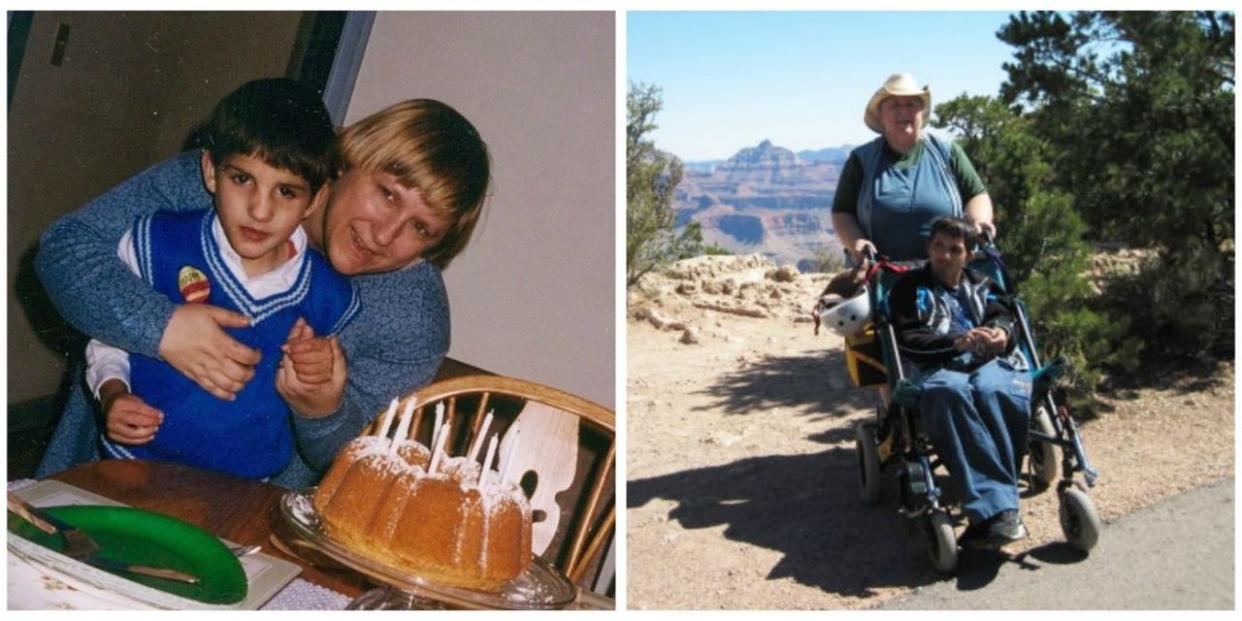

For 26 years, five months and one day I was the primary caregiver for my son Matthew, who was born with brain defects. He never functioned beyond the level of a toddler-he was nonverbal, couldn't walk well, and required help eating and drinking. Doctors told me that his mental capacity was very low, but during our short time together, my son taught me so much about myself and the world.

As an infant, Matthew seemed normal. But by 16 months old, I noticed he fell down far more than the other kids in his daycare, so my then-husband Ed and I took him to our pediatrician. To test Matthew's balance, the doctor went down to the far end of a 15-foot hallway and called Matthew to walk toward him. Matthew fell twice. The doctor suggested I schedule a CAT scan.

When the doctors told me what my son's limitations might be, I cried. Our future would be much different than what I'd imagined on the day he was born.

One night soon after that doctor's visit, Matthew had a seizure while my mother was babysitting him so I could attend a professional meeting. When I got to the emergency room an hour later he was still seizing.

Once he stabilized, the doctors transferred him to a larger hospital nearby. From the front seat of the ambulance, I wasn't sure if Matthew could see or hear me, but I started to sing some hymns that I sang regularly to him at bedtime. At one point Matthew stopped breathing briefly. As the ambulance crew gave him air through a mask, I kept singing. I like to think the songs comforted him.

After the seizure Matthew had the planned CAT scan, plus other imaging. As the doctors inspected his brain images, they found several major abnormalities. When the doctors told me what my son's limitations might be, I cried. Not that I loved Matthew any less, but our future would be much different than what I'd imagined on the day he was born.

In many ways, though, Matthew was a typical kid. He loved panda bears and all sorts of cookies. He enjoyed being around children his age, and he was also a terrible flirt. Sometimes therapists would have trouble getting him to concentrate because all he wanted to do was hold their hands and play with their brightly colored fingernails. Or Matthew would be totally distracted by trying to touch their dangling earrings.

He loved horseback riding, too. When he was five, he started going to therapeutic riding. He liked the horses' movement, going up and down, and the noises they made. His teacher said that his laughter was the sound of therapeutic riding. Anything involving movement or tactile stimulation was a joy for him.

Walking alongside Matthew as he developed and grew, I learned so much. For one thing, raising Matthew taught me a lot about trust. Every time we went down stairs holding hands, he would step off into space with his limited ability to balance, trusting me to keep him from falling.

Sitting with Matthew handling fallen leaves, pine cones, animal crackers, or the fur of his stuffed bear, I learned about the beauty and wonder hidden in every object. Once on a trip to the Grand Canyon, Matthew and I watched a group of condors soar over a ravine. Matthew was entranced. Then a flock of ravens appeared and started making raucous noises right in front of us, which sent him into a fit of laughter.

My son also convinced me of the joy that exists in music. We often went to our local community theater in Hershey, PA. Together we saw Little Shop of Horrors, The King and I, Into the Woods Junior, and The Best Christmas Pageant Ever. Matthew just loved all the dancing and jumping and singing. The week before Matthew died, we saw Fiddler on the Roof.

During church, we would face each other and hold hands. Then I would sing while we rocked back and forth in the aisle. Sunday to Sunday, Matthew would know when the singing was coming. How many teenage boys do you know who are thrilled to dance in the aisles with their mothers at church? Our pastor even thought that he was able to hum on the same pitch as the choir.

At school, because Matthew had a full-time aide, he could attend regular music classes, like middle school band and high school choir. He couldn't participate, but he loved observing. The other students claimed Matthew could tell if they made a mistake and would hum when they got it right. Together they experienced the power of music.

Having a child with special needs, I learned a lot about accessibility―like how to investigate buildings, bathrooms, playgrounds, and parking areas. Matthew is gone, yet I still find myself evaluating new places I visit.

Because of Matthew, I also gained knowledge of things like how to use a gastrostomy tube, how to help someone having a seizure, and what to call certain parts of the brain. At times, doctors or medics would assume I was a nurse because I knew their language. That doesn't just go away when the person goes away, either.

It's now been 4 years and 11 months since Matthew passed away. We had just come home from a trip to Boston. What follows I wrote the day of his funeral, in my pink paisley diary. I carried that book in my purse for a long time after my son's death. I still like to keep it where I know I can lay hands on it when I want to read through it.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

After the service in the church, the ushers turn Matthew so his coffin goes down the aisle feet first. I walk behind it singing "Abide with Me." Give the hymn all I've got. We sang this at the end of my father's funeral, too. I sang it to Matthew many times over the years-at bedtimes, in the car, in waiting rooms, in ERs, in ambulances. We follow to the exit.

"When other helpers fail and comforts flee; help of the helpless, oh, abide with me."

Marilyn, my sister, and I stand in the parlor-me singing, her holding me-as they go out and down the steps to the hearse. The room's acoustics are good, I notice. Marilyn says something about that hymn always making her cry. I reply that I sing instead of crying, which is mainly true.

"Swift to its close ebbs out life's little day; earth's joys grow dim; its glories pass away;"

If I concentrate on singing, it keeps the tears at bay and sometimes something else takes over and the music sings me. Kind of a singer's high. The funeral director comes back in and says they could hear me clearly outside. He seems impressed.

"Hold thou Thy cross before my closing eyes; shine through the gloom and point me to the skies;"

As I visualize saying goodbye to Matthew at the church, I realize that it's the first time he was out in public when he wasn't wearing diapers. He's dressed in regular boxer shorts and a normal undershirt, like any other young man his age leaving home. Not for college, not for the Armed Forces, not to marry, but to go to his true and eternal home with the God who brought him into being.

"Heav'n's morning breaks, and earth's vain shadows flee; in life, in death, O Lord, abide with me."

I'm no longer my son's caregiver, yet because of him I try to care more deeply about others. I've become more aware of the talents and needs of people with disabilities. After Matthew died, I worked for about a year and a half at a short term mental health facility that also served people who had a dual diagnosis of developmental delay and mental health problems.

When Matthew was young, I slowly made my peace with the things my son would never do, balanced against the things that he could do.

For part of my time there, I worked with two autistic young men as a direct caregiver, doing support tasks like those I had done for my son. Through that experience, I realized all over again what a blessing my Matthew was.

When Matthew was young, I slowly made my peace with the things my son would never do, balanced against the things that he could do. He could smile; he could laugh; he could make eye contact and reach for my face; he could hold my hand tightly to help himself get up when he fell; he could run. Matthew loved to run. Even though he fell down a lot, he got up and kept going.

Matthew's life was a gift, not a tragedy. Every day his life reminds me to touch the world, to sing with the world, to reach out for the world, to get up and keep running towards the world and not away from it.

You Might Also Like