Snow Science Storytellers: How Avalanche Forecasters Communicate Risk

On crisp winter mornings, the Utah Avalanche Center employee responsible for publishing daily public avalanche forecasts in the Salt Lake City, Utah, area arrives at an office near the international airport. There, they drink from the proverbial fire hose, translating raw data into digestible backcountry safety messaging. The task is weighty—failures to communicate where and when avalanches might occur could endanger hundreds, if not thousands, of backcountry skiers.

The UAC's director, Mark Staples, likens avalanche forecasting to storytelling: "This is an article that we're writing throughout the whole season, and we're just writing little chapters of it." To write each chapter—or individual forecast—any given avalanche forecaster has to know how the story started. Continuity is essential, as avalanche-producing instabilities in the snowpack can exist for weeks, months, or even an entire winter. Like a well-written antagonist, their threat always looms, forcing forecasters to build what Staples calls a "mental model" of the snowpack.

For forecasters, dialogue is a crucial element of this process. "The real secret sauce is just the informal ongoing communications," said Staples. UAC forecasters rely on each other throughout the season alongside outside sources of information, like ski resorts, weather data, and crowdsourced avalanche observations submitted by backcountry users. Time spent studying the snow's intricacies in person is vital, too. On average, a forecaster-conducted field day supports every two UAC avalanche forecasts. All the bits of knowledge forecasters accrue slot into their mental models.

"What [this] means is that when that forecaster walks into the office at 4 am, they're not just starting from scratch," Staples explained. "They have been watching the weather and the snowpack and avalanches and they've been discussing it with our other forecasters all season long."

Daily forecasting schedules sometimes differ from avalanche center to avalanche center. For instance, forecasts are published in the evening at Washington and Oregon's Northwest Avalanche Center. After conducting any necessary field snowpack observations, NWAC forecasters are responsible for writing, editing, and publishing two to three daily regional forecasts (NWAC positions its forecasters geographically to intimately know and write about two forecast zones—the third potential forecast might arise when another forecaster takes time off). Each forecast is about 500 words.

"When I come in from the field until I press publish, it's pretty game on," said Dallas Glass, NWAC's deputy director. "I mean, you're kind of just go, go, go, go, go." Once, Glass told an Associated Press reporter about NWAC's evening forecasting schedule. Her paraphrased response? "That's the nuttiest deadline I've ever heard."

Similar to journalism, avalanche forecasts are a one-way transfer of information, meaning there's considerable pressure on forecasters to get it right. After a forecast is published, there usually isn't a public question-and-answer session where backcountry skiers can ask for clarification on sections that don't make sense. "To some extent, figuring out the avalanche problem, the danger rating and those things—that becomes the easier part of the job," Glass said, noting that the writing skills associated with avalanche forecasting are often underappreciated. "It's the communication piece that's so challenging."

When publishing avalanche forecasts, avalanche centers must meet their users at varying levels of backcountry know-how. What's useful for an advanced backcountry skier may not be for a complete novice, and vice versa. Avalanche centers tackle this challenge with an "inverted triangle" approach, which presents another parallel between avalanche forecasting and journalism. Reporters and avalanche forecasters both avoid burying the lede.

In avalanche forecasts, the simplest information typically comes first—think a forecast zone shaded red to indicate danger on a digital map—followed by increasingly granular information like forecast discussions and specific avalanche problems. Most people understand a bright-red warning sign, but the implications of a wind-loaded, north-facing slope are more difficult to parse.

Ryan McGinnis/Getty Images

"Everyone should check the forecast," Staples said, stating that, with its forecasts, the UAC aims to meet the needs of diverse users, from "a scout group going on a snowshoe hike" to "someone who's spent 20 to 30 years in the backcountry."

Storied snow scientist and educator Bruce Tremper first became involved in avalanche forecasting and snow science several decades ago. He was surrounded by fellow experts, many of whom, in his opinion, struggled to convey snow safety messaging to the public. "Boy, he sure talked like a scientist," Tremper said, describing one of his colleagues. "You kind of needed to be a scientist to understand what he was telling you." (He clarified that said colleague was "amazing"—just too esoteric for the average backcountry skier.)

That gap—between the experts and the public—prompted Tremper to pursue avalanche safety communication efforts, which, he said, comprised "90%" of his career. During our conversation, he quoted fellow avalanche expert Dale Atkins: "We don't have a forecasting problem. We have a marketing problem."

Tremper wrote the best-selling Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain. The book is full of metaphors, stories, analogies, anecdotes, and handy graphics that, to me—and presumably a significant number of fellow skiers—illuminated the risks associated with avalanches in a way I'd never experienced. It's how I wish every textbook I've read were written. This, of course, was intended.

"The human brain was designed for emotional response and social interactions," said Tremper. "So that's the way you have to approach people; you have to tell them stories and to give them analogies and metaphors. You need to put it in terms that they can understand." Humans often struggle with numeracy—the ability to effectively use numbers, probabilities, and statistics in decision-making—forcing avalanche forecasters like Tremper to find better, more creative ways to communicate danger.

After working avalanche control stints at Bridger Bowl and Big Sky, Tremper became the director of the UAC in 1986 (Staples replaced Tremper in 2015). Back then, the UAC's public forecast system was a hotline. Backcountry skiers would call the phone number and hear a pre-recorded message describing that day's avalanche conditions. The UAC's recording machine only had a few available lines, so "people had to just sit at their phone and call over and over and over until they could finally get through," said Tremper. In what he believes was his second year as director, the UAC purchased a digital multi-line announcer, which eventually allowed the Center to increase its simultaneous caller capacity to roughly 20.

The internet changed everything. Avalanche centers, including the UAC, had the opportunity to publish forecasts with detailed, color-coded graphics as the internet evolved. Tremper noted that this development was "revolutionary." Suddenly, avalanche centers had a digital megaphone. During the 2022-2023 ski season, 4.3 million users visited the UAC's website—a far cry from the days of bottlenecked recording machines.

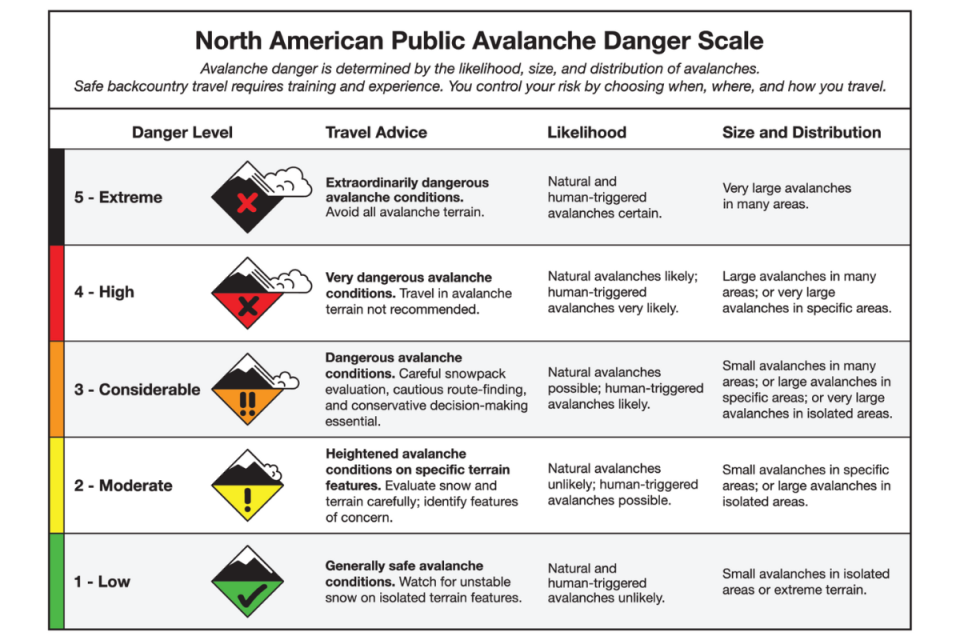

Most avalanche center websites in the U.S. feature interactive maps that shift colors based on the avalanche danger in a given zone, ranging from green to black. Avalanche center maps borrow these colors from a central element of avalanche forecasting: the North American Public Avalanche Danger Scale (NAPADS), which communicates daily avalanche danger with five levels across the U.S. and Canada.

Avalanche.org

Despite the name, the NAPADS, like the Statue of Liberty, is a European import. Starting in the 1970s, the U.S. relied on a four-level rating system for public avalanche danger. Meanwhile, European avalanche rating systems across the pond differed widely from country to country. Some had four levels—others had ten or more. "It was just a mess," said Tremper, explaining that you could cross a national boundary and confront a danger scale unlike the one you have at home.

The lack of consistency created confusion, which is the last thing you want as an avalanche forecaster. The Europeans alleviated this problem by developing a unified five-level scale in 1993. For the sake of international continuity, that scale came to North America in the mid-1990s. After an extended revision process that involved several avalanche scientists—including Tremper—the borrowed five-level North American scale became the NAPADS we know today. To finalize the NAPADS, the team drew on experts in risk communication and graphic design.

Years after its implementation, Tremper still thinks the NAPADS could be better. He takes particular issue with the use of the word "considerable," which describes the third level of avalanche danger (during the NAPADS infancy, the proposed word "considerable" generated controversy amongst other forecasters). Tremper views this word as imprecise, a thesis he tested by writing the five NAPADS avalanche danger levels on notecards—"low," "moderate," "considerable," "high," and "extreme"—before visiting a ski resort cafeterias and asking skiers to rank the five NAPADS categories in order of danger. The survey involved about 200 skiers.

"I could see that a quarter of the people were putting the word 'considerable' in the wrong place," he said, explaining how those he quizzed sometimes thought "considerable" designated lower avalanche danger than intended. "That's a big problem." Tremper conducted a follow-up survey—using only colors and numbers instead of words—and found that skiers almost always organized the NAPADS’ danger levels in the correct order: "The problem came with words, and only with the word 'considerable.'"

Tremper posits that the NAPADS, which underpins the modern public avalanche forecast system, isn't perfect, as do some contemporary researchers. Yet, yearly avalanche fatality numbers nationwide indicate that, overall, the forecasting project has made positive headway. "Way more people are in the backcountry than there used to be," said Staples, the UAC's current director. "But the number of people dying in avalanches—that number has been fairly flat."

A letter to the editor written by snow science experts and published in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine estimated that if avalanche fatalities had increased alongside growing backcountry usage, the U.S. could be seeing 200-plus avalanche fatalities each winter. That hasn't happened. This season, avalanches killed 16 backcountry users in the U.S.

Staples noted that avalanche centers and forecasters are only one part of the encouraging avalanche safety communications picture. He pointed to backcountry guides and avalanche educators—like the American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education—as valuable collaborators. The last piece of the puzzle? You. For every avalanche forecast that gets published, there needs to be a receptive backcountry traveler. "The bad news is that the enemy is us," wrote Tremper in Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain. "And that is the hardest enemy of all to conquer."

Related: Australian Ski Resort Fires Up Snowguns As Winter Approaches

Don't miss another headline from POWDER! Subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected with the latest happenings in the world of skiing.

We're always on the lookout for amusing, interesting and engaging ski-related videos to feature on our channels. Whether you're a professional or just an amateur, we want to see your best footage and help you share it with the world. Submit your video for a chance to be featured on POWDER and our social channels. Be sure to subscribe to our YouTube channel to watch high-quality ski videos.