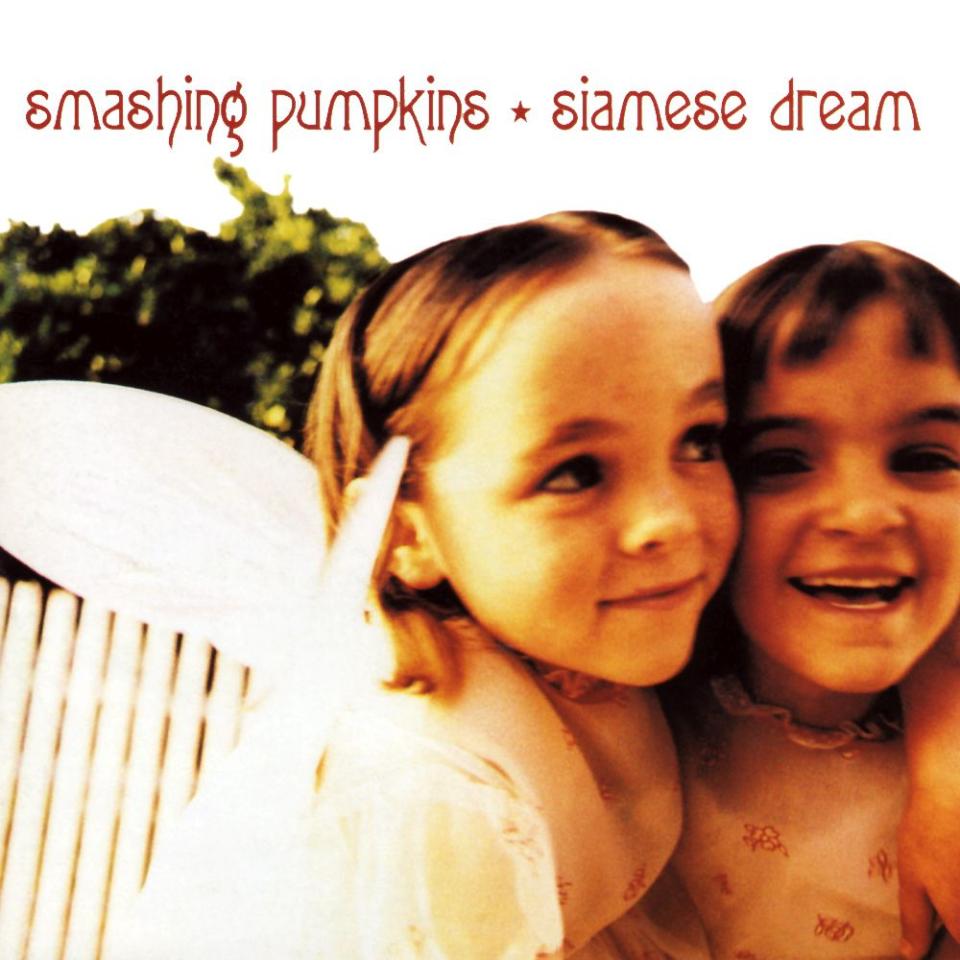

The Smashing Pumpkins’ Siamese Dream: The Album Chicago Loved by the Band It Hated

On July 9, 1988, Billy Corgan, James Iha, and a tragically nameless drum machine debuted as The Smashing Pumpkins during a Saturday night gig at a bar called Chicago 21 Club way out on the city’s Polish West Side.

Presumably, in the early morning hours of July, after the proto-Pumpkins finished up their set, someone in attendance sat at the bar, nursing a sweaty bottle of Okocim, and became the first person in Chicago to have this thought: “I liked the music well enough, but something about that frontman really chaps my ass.”

After three decades of mutual ambivalence, Chicago still can’t decide whether it loves The Smashing Pumpkins or hates Billy Corgan. The fight is ongoing. In August, the mostly reunited band (minus bassist D’arcy Wretzky, whose 2018 feud with Corgan was as personally ugly as it was musically regrettable) will play to a sold-out crowd at the United Center during the first of a two-day homecoming.

Then again, as recently as last year, Corgan made The Chicago Reader’s Worst of Chicago list, with critic Peter Margasak proudly declaring, “I’ve never liked any of his music” before knocking Corgan’s rightly knockable recent offenses and putting the onus of defense on Chicagoans themselves. “If you claim to love the band’s music, be honest: Without a nostalgic attachment to it, would you really be able to stomach Corgan’s whine on ‘Today’?”

Admittedly, an anniversary retrospective is perhaps not the place for answering questions of bias. However, I do think that the answer to the above question is, for a great many people in Chicago and elsewhere, “yes,” primarily because “Today” comes from the one truly unimpeachable album in Corgan’s bombastically uneven catalog: Siamese Dream, the record Billy Corgan wrote to shut Chicago up once and for all.

To fully appreciate the legacy of Siamese Dream, which came out 25 years ago this week, it helps to understand where The Smashing Pumpkins fit within the Chicago music scene of 1993. Actually, “fit” may be the wrong word here. By all accounts, the Pumpkins began as an anomaly and stayed that way. Sonically, they drew inspiration from the looming riffs of Black Sabbath and eyelinered radio goth of The Cure and Depeche Mode at a time when Chicago’s scenesters often rallied around the uncompromising antagonists of Touch and Go or the industrial heavies of Wax Trax. Temperamentally, they bore an even starker difference: they didn’t care about selling out.

As The A.V. Club’s Steve Hyden put it in a 2010 retrospective on Chicago’s early-’90s rock boom, “There was no clearer statement of disreputable intent (if not out-and-out shittiness) in the underground than wanton commerciality.” It also didn’t hurt, of course, that until the early ’90s, most Chicago bands weren’t commanding much attention from major-label A&R reps anyway. Unlike many bands who regarded radio viability as either an unfortunate necessity or a sign that your music was no longer worth listening to, The Smashing Pumpkins never shied away from their ambitions to write anthems aimed at the widest possible audience. That willingness to, as The Chicago Tribune’s Greg Kot put it, “play the game” and “deliver singles” made them (even more than other Class of ’93 major-label signees Liz Phair and Urge Overkill) desperately uncool among the alt kids in Chicago and beyond.

Smashing Pumpkins’ Classic Lineup: Billy Corgan, Jimmy Chamberlin, James Iha, and D’arcy Wretzky

Unsurprisingly to anyone familiar with him, the harshest criticism came from Steve Albini, the caustically uncompromising producer whose relationship with The Smashing Pumpkins soured after they skipped from Sub Pop to Caroline in advance of Gish. In an infamous 1994 letter aimed at Chicago Reader critic Bill Wyman and his perceived boosterism of Chicago’s major-label trio, Albini decried Corgan’s band as “frauds,” “bullshit,” and, perhaps most damningly, “REO Speedwagon” before telling Wyman to “clip your year-end column and put it away for 10 years [and see] if you don’t feel like an idiot when you reread it.”

Of course, Corgan gave back as good as he got and sometimes better. After Gish earned the band its initial national notice in 1991, Corgan often used interviews to diss the city and its perceived parochialism to anyone who would listen (in one particularly brutal 1992 interview with Nick Jones of the now-defunct UK music mag Spiral Scratch, Corgan describes his city as “a dead music town” whose scene is mostly populated with “eight thousand Replacements and two thousand Husker Dus” before concluding “Nobody cares.”). He was also famously at odds with Chicago’s critics; for the relatively mild critiques found in a 1993 profile that appeared in the Chicago Sun-Times, journalist Jim DeRogatis found himself publicly excoriated as “that fat fuck from the Chicago Sun-Times.”

Written just before Siamese Dream came out, DeRogatis’ article contains a single line that sums up Corgan’s feelings around that time: “For somebody who’s so successful, he sure is miserable.” That, as we know now, was certainly true at the time of the record’s recording. Tasked with building off of the success of Gish, Corgan found himself with a band whose drummer (Jimmy Chamberlain) was veering ever deeper into substance abuse and whose other two members (Iha and Wretzky) had just broken up. The band decamped to Atlanta to put some distance between themselves and the distractions, but the stresses of Chicago remained.

Once again guided by learned grunge producer Butch Vig, all members of The Smashing Pumpkins appear on Siamese Dream (Chamberlin, once forced to drum “Cherub Rock” until his hands bled after disappearing during the sessions, even made a physical down payment), but the record itself is mostly a tortured two-way conversation between Vig and Corgan. Seeking both a huge sound and true sonic perfection, Corgan would frequently demand 16-hour days and lay down upwards of 50 guitar tracks per song. When they finished recording, the two brought in My Bloody Valentine collaborator Alan Moulder to engineer the record, reportedly keeping him at it for six weeks until the job was done. In a 2009 forum Q&A, Vig called the record “one of the most difficult albums I ever made.” He also recalled the morning after the record was finished:

“I woke up at noon the next day at the Beverly Garland Hotel on Vineland with all the curtains closed and listened to the album all the way through in pitch black. I couldn’t see anything, I could only listen … and I knew we had something special.”

What Vig heard that day remains one of the high points of ’90 music, and easily one of the most accomplished Chicago records of all time. Siamese Dream dares its would-be detractors from the start; before it even gets to its lyrical takedown of both Albini-style gatekeepers and opportunistic industry moneymen, the opening drum rolls of “Cherub Rock” resemble nothing so much as the countdown before a circus-style spectacle, and what’s more brazenly commercial than that?

“Cherub Rock” was just one of the record’s hard-to-hate singles; the others (the suicidal “Today”, the vengeful “Disarm”, and the forward-looking “Rocket”) only inspire real ire today because they almost singlehandedly inspired legions of equally passionate but vastly less talented imitators that clogged up alternative radio for the rest of the decade. The real magic in listening to Siamese Dream today lies in the moments you might’ve forgotten. Maybe it’s the transcendent closing solo on “Geek U.S.A.” or the surprising lighters-aloft sincerity of “Mayonaise”. Maybe it’s “Hummer” and its shameless Kevin Shields worship that translates into a vox-forward, Americanized My Bloody Valentine without the anonymity or inborn Irish shame. Maybe it’s just Corgan and his own near-suicidal exhaustion; for much of the record, he sings like a trapped ghost, one that’s trying to either scream or cry its way out of a sealed vacuum tube.

Whatever moment sticks with you, it’s probably one that conjures this distinctive feeling: the surprise and dread of realizing that the picked-on, self-sabotaging dude that everyone makes fun of just produced something so undeniable that it not only confirms his talent, but (and here’s where the hairs on your arm stand up) signals that he’s only just getting started.

The release of Siamese Dream certainly didn’t end Corgan’s feud with Chicago’s music scene; Albini still wrote his letter, and Corgan still forced Jim DeRogatis to review a 1995 Pumpkin show at the Double Door from a lawn chair in the alley after he banned all Chicago critics who wouldn’t swear not to file a report. It also didn’t guarantee the Pumpkins any truly enduring success or respectability. However, it did ensure that, whenever an argument against the band did arise, Corgan and The Smashing Pumpkins could no longer be dismissed as posers or hacks by most reasonable metrics. The skeptics of Chicago’s music world didn’t have to like him, but they had, on some level or another, to respect him.

Twenty-five years later, most do, at least when it comes to Siamese Dream. The still-skeptical staff of the Reader excepted, the next generation of Chicago critical outlets gave the record its retroactive due; we named the album one of the 100 best of all time in 2010 (the highest-charting release for a Chicago band on that list, and the only one from The Smashing Pumpkins), and Pitchfork gave it a rare perfect 10.0 upon its reissue in 2011. In that review, writer Ned Raggett (who, it should be noted, hails from the definitely-not-Chicago city of Bremerton, WA) concludes that “no matter your take on its mastermind or his divisive whining/sighing vocals, [Siamese Dream] is an embarrassment of musical riches.”

I agree. I also hope that Bill Wyman did save his year-end column from 1993, the one in which he praised the Pumpkins, along with Liz Phair and Urge Overkill, for their “explicit rejection of much of the insularity that increasingly characterizes underground music and the fringes of underground music in America.” Twenty-five years later, long after poptimism helped us accept Siamese Dream as a masterpiece and the internet rendered arguments about indie cred into one more relic of a fading monoculture, his takeaways have aged with more grace and foresight than Albini, Corgan, or just about anyone else.