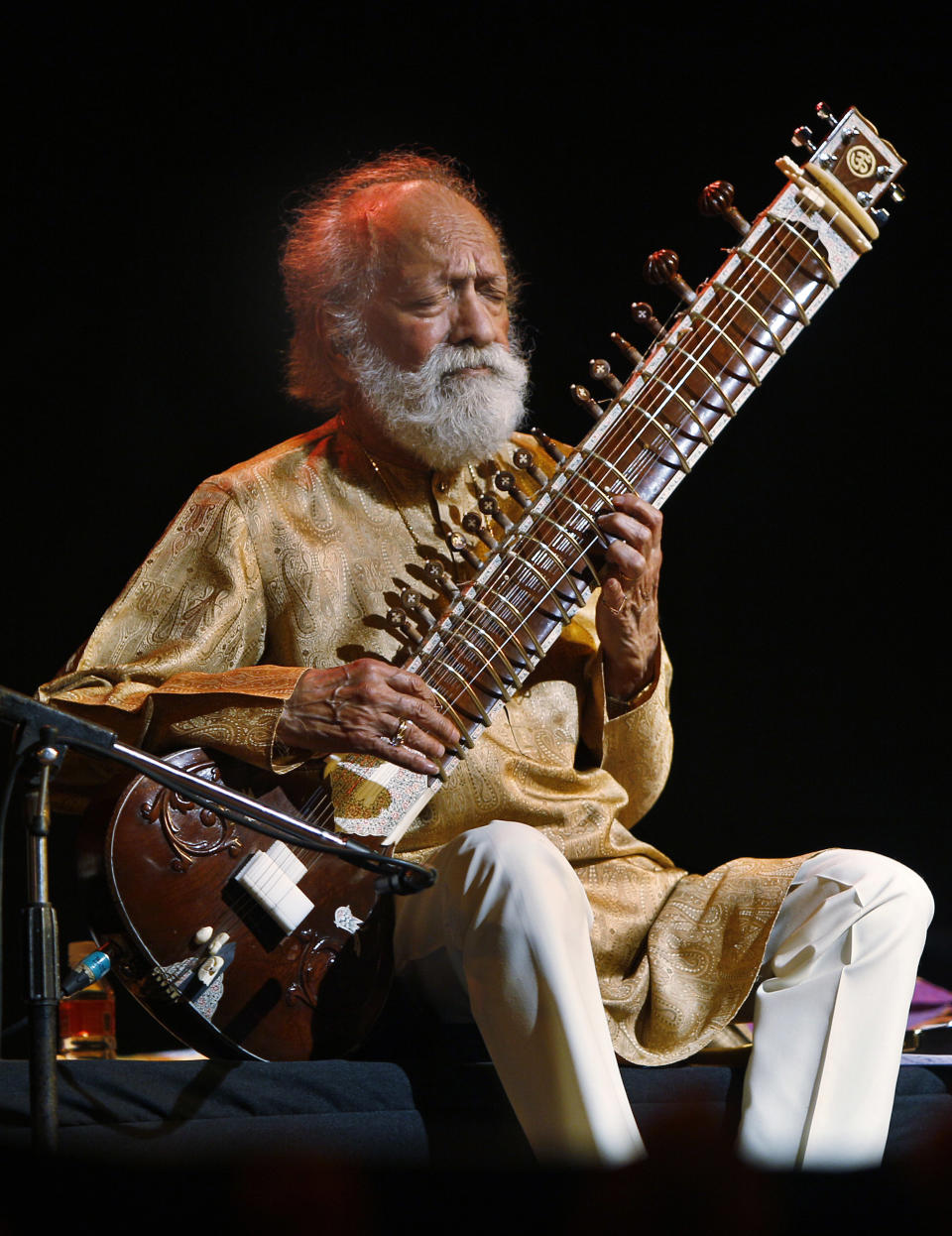

Sitar maker: Ravi Shankar's legacy inspires others

NEW DELHI (AP) — The walls of Sanjay Sharma's music shop are lined with gleaming string instruments and old photographs of legendary musicians.

Beatles George Harrison, John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Indian classicial musicians Zakir Hussain, Shiv Kumar Sharma and Vishwamohan Bhatt. And the man who brought these two very different musical worlds together: Ravi Shankar.

Like his grandfather and father before him, Sharma built, tuned and repaired instruments for the sitar virtuoso, who introduced Westerners to Indian classical music, and through his friendship with Harrison became a mainstay of the 1960s counterculture scene.

From his tiny shop tucked into the crowded lanes of central Delhi's Bhagat Singh market, Sharma traveled the world with Shankar. Late in the maestro's life, as his health and strength flagged, he even designed a smaller version of the instrument that allowed him to keep playing.

Shankar, who died Tuesday at age 92, was "a saint, an emperor and lord of music," Sharma says in a tribute posted to the website of his sought-after shop, Rikhi Ram's Music.

"When I opened my eyes there was him," says Sharma, 44, surrounded by display cases full of sitars, sarangis (a stringed instrument played with a violin-like bow), guitars, tabla drums and sarods, a deeply resonating instrument played by plucking the strings.

Shankar "was music and music was him," he says.

Sharma's grandfather started the business in 1920 in the northern city of Lahore, now in Pakistan. He met a young Ravi Shankar at a concert there in the 1940s. Following the India-Pakistan partition and the relocation of the shop to New Delhi, the family began making sitars for Shankar in the 1950s.

By then, the musician was already famous in India and beginning to collaborate with some of the greats of Western music, including violinist Yehudi Menuhin and jazz saxophonist John Coltrane.

The Beatles visited in 1966 and bought instruments, memorialized in some of the many photographs that line the shop's walls. Another shows Shankar's daughter and the heir of his sitar legacy, Anoushka Shankar. But there is no picture of another Shankar daughter, American singer Norah Jones, who was estranged from her father.

Sharma's own father succeeded his grandfather as the supplier of Shankar's sitars. And then Sharma himself in the 1980s.

The bedroom-sized shop has two counters, one for conducting business and one for working on instruments under the beam of a large work lamp. Wood shavings and dust cover the floor of a workshop at the back.

As he chatted with visiting Associated Press journalists on Thursday, Sharma worked on a sitar, peering through his glasses as he used a mallet to hammer in a new fret. He plucked the strings, and as the sound resonated around the room, he leaned close in to the instrument and listened intently to the vibrations. Satisfied with the results, he moved on to the next fret.

It takes 15 months for a sitar to be ready for use. The actual crafting of the instrument from red cedar and hollowed-out, dried pumpkins takes three months. Then, it is left untouched to go through what is called "Delhi seasoning," in which the extremes of New Delhi's climate — blistering summer, followed by a brief monsoon, and a near-freezing, three-month winter — work their magic.

In 2005, a serious bout of pneumonia left Shankar with a frozen left shoulder.

"He was growing old and he wanted to experiment and change the instrument" so he could continue playing, Sharma says.

Sharma, a large, balding man, created what he calls the "studio sitar," a smaller version of the instrument. But holding it was still difficult. So Sharma went to a Home Depot near Shankar's San Diego, California-area home and bought some supplies to build a detachable stand.

The musician was thrilled. Sharma says Shankar told him, "Your father was a brilliant sitar maker, but you are a genius."

Shankar was performing in public until a month before his death. Despite ill health, he appeared re-energized by the music, Sharma said.

Now, as Sharma mourns the giant of Indian music, he also worries about the future of the art itself. He sees traditional Indian instruments gradually losing their place in their own country to zippy, electronic Bollywood music.

"We are losing the originality and the core of our Indian music," says Shankar, himself a trained Hindustani classical musician who plays the sitar and tabla, the Indian pair-drums.

At the same time, Shankar's work as a global ambassador of music has borne fruit, Sharma says: "Because the music has gone to the West, we're getting lots of new musical aspirants from the Western countries."

When jazz artist Herbie Hancock was in New Delhi a few years ago, he stopped by Sharma's shop to buy a sitar.

And in one of the shop's display windows gleams a newly crafted sitar made of teak.

"That," Sharma said, "is for Bill Gates."