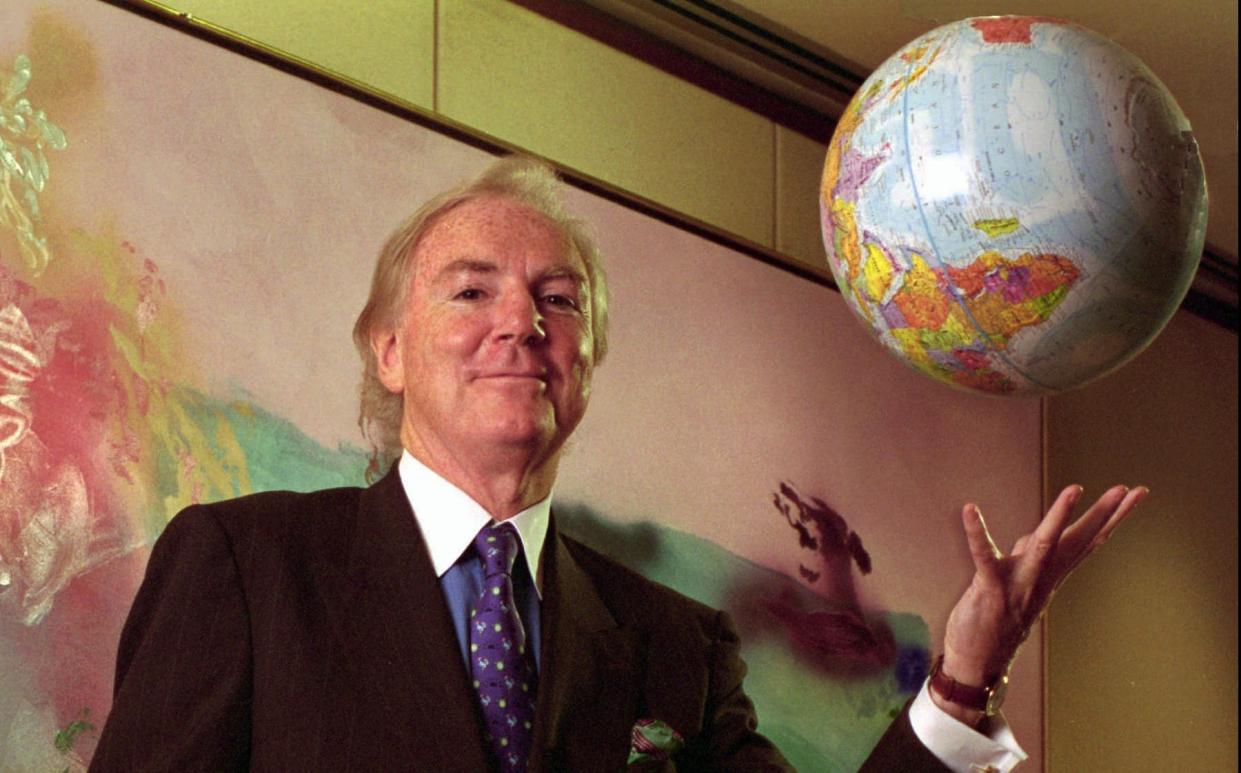

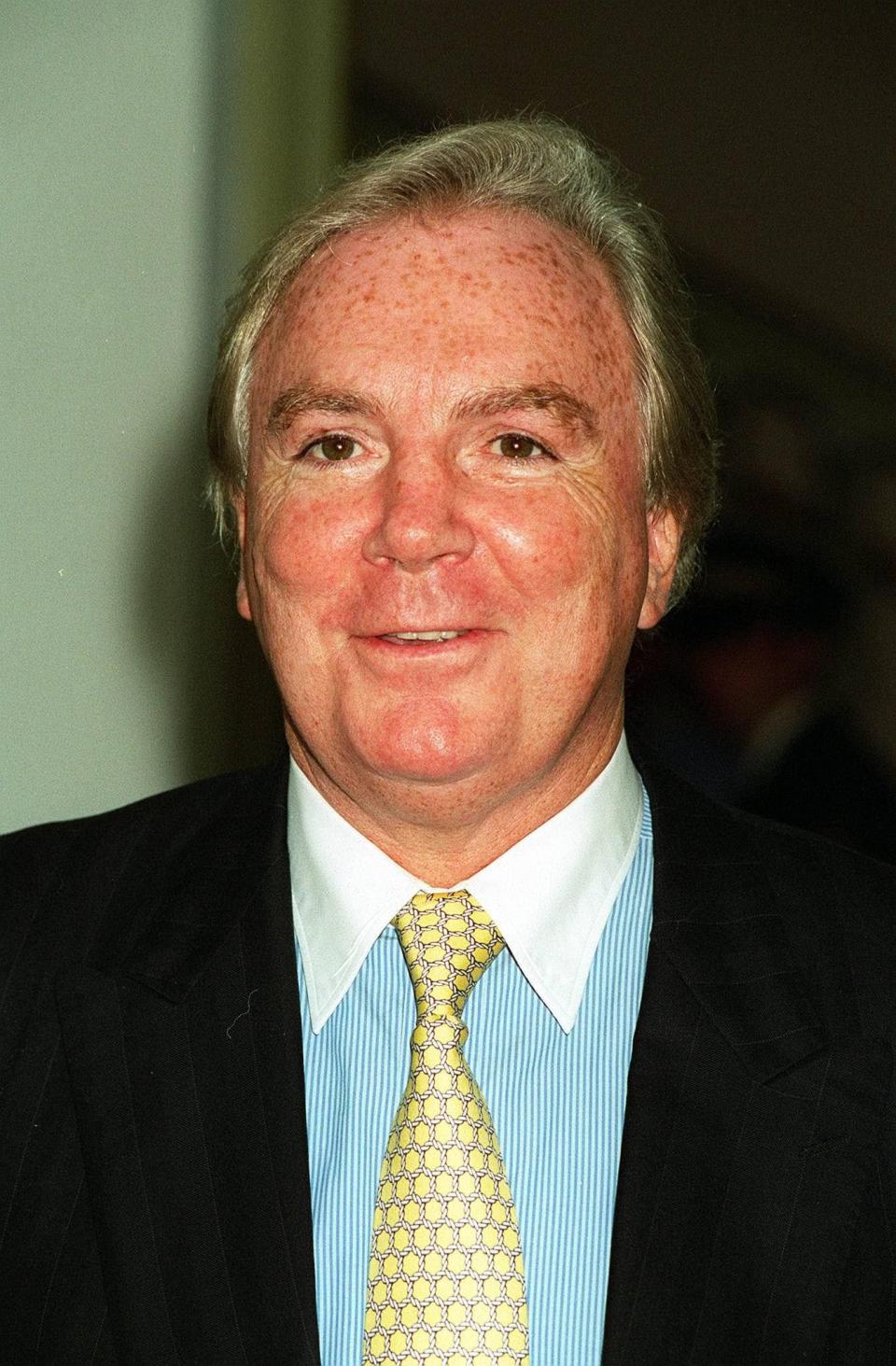

Sir Tony O’Reilly, princely Irish rugby hero and tycoon who fell into bankruptcy – obituary

Sir Anthony O’Reilly, who has died aged 88, achieved fame first as an Irish rugby international and British Lion; second, as the creator of Kerrygold butter; and third, as a charismatic international business leader and newspaper tycoon who was often described as Ireland’s first billionaire – until he was overwhelmed by financial difficulties.

Tony O’Reilly was the beau idéal of modern Ireland two decades before his native country reinvented itself as the “Celtic Tiger”. His style was princely and his ambition insatiable; the drive and stamina that enabled him to run complex businesses simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic, for himself and for his long-time employer HJ Heinz, were extraordinary.

He was, as one commentator put it, “a hero from a time when Ireland was short of heroes”, and when he finally fell into bankruptcy, Irish opinion was sharply divided: between those who felt he had arrogantly flown too close to the sun, and those who were genuinely sad to see this giant of his generation brought low.

It was rugby that launched O’Reilly’s rise. He won his first cap for Ireland in January 1955, in his first senior season. He played 29 times for his country, the last time in 1970. A fine attacking player, he was less good in defence, and Irish supporters always maintained he played better for the British Lions, with whom he toured twice, than for his country.

It is true that his most famous exploits were achieved in the Lions’ red shirt: on the 1955 tour of South Africa, O’Reilly scored 16 tries in 15 matches, a Lions record, causing the Johannesburg Star to comment: “Men like Cliff Morgan and Tony O’Reilly will be remembered here as rugby geniuses of an order seldom seen even in this country of great footballers.” In New Zealand four years later, he went one better, scoring 17 tries, a Lions tour record which still stands.

O’Reilly qualified as a solicitor in 1958 after taking a law degree at University College, Dublin. He decided not to practice law, however, and went to work in England as a management consultant, returning in 1960 to join an agricultural merchant in Cork. He got on well with the Co-operative chiefs who dominated Irish farming and it was the recommendation of one of them, allied to his fame on the field, which gave him his first big break.

At 25, O’Reilly became general manager of the Irish Milk Board (An Bord Bainne), a state company newly established to market Irish produce abroad. There he masterminded the launch of Kerrygold butter as a gambit to reduce dependence on bulk dairy sales in overseas markets. The venture was underpinned by hefty government (and later EEC) subsidies, but achieved a high brand profile and market share in Britain. “The biggest success of my life was indisputably Kerrygold,” O’Reilly once said.

In 1969, O’Reilly left Ireland to work for the ketchup-to-baked-beans manufacturer HJ Heinz, initially in England and from 1971 at its Pittsburgh headquarters – but he persuaded his new bosses to let him continue building his private business empire in Ireland, an occupation he referred to as “playing Celtic monopoly”.

At Heinz, he quickly established himself as a high-flier. By 1973 he was chief operating officer of the group; in 1979 he became chief executive, and from 1987 to 1998 he was the first non-family chairman, having succeeded Jack Heinz. Throughout the 1980s the company generated spectacular returns for shareholders, and O’Reilly was recognised as a master of the art and science of global brands.

His stellar career at Heinz contrasted with the troubled history of his Irish businesses. In the early 1970s he built a small conglomerate, Fitzwilliam Securities, but in the slump of 1974 its profits collapsed and his banks threatened liquidation. For a time, he flew over from America every weekend in an attempt to save it, succeeding only by selling almost all of its assets. Another O’Reilly company, Atlantic Resources, lost £40 million fruitlessly searching for oil off Ireland’s west coast in the 1980s.

But there were also what seemed for many years to be notable successes. Through the acquisition of the Irish Independent newspaper group in 1973, O’Reilly became Ireland’s leading press baron and later expanded his publishing interests to encompass some 200 newspapers in Australia, South Africa and the UK, where he bought a stake in the Independent and Independent on Sunday in 1994 and took full ownership of them in 1998.

In 1990 he formed a consortium to buy control of Waterford Wedgwood, the merger of Ireland’s historic Waterford crystal glass business with Wedgwood bone china in England. The group was beset by labour problems and rising foreign competition, but O’Reilly succeeded in turning it around, raising its marketing profile and expanding it by acquisition. In the 2000s, however, the impact of globalisation took its toll. O’Reilly (with his brother-in-law Peter Goulandris) injected some €400 million of family money to keep Waterford Wedgwood afloat, but it went into receivership in 2009 (the brands were subsequently revived by Finnish owners), wiping out a substantial slice of his fortune.

It was said that O’Reilly might have survived disaster in either Waterford Wedgwood or Independent News & Media, where he was chief executive, but not in both. The heavily indebted newspaper group was also descending into trouble as the 2008 financial crisis took hold – and another Irish billionaire, Denis O’Brien, had built up a stake that enabled him to challenge O’Reilly for power. O’Reilly was forced to accept retirement on his 73rd birthday in 2009, and the title of president emeritus. The London Independent titles were subsequently sold for £1 to the Russian businessman Alexander Lebedev.

O’Reilly’s personal finances were crippled by the loss both of his income as chief executive of INM and a lavish stream of dividends which the company had hitherto paid, but which O’Brien cancelled. He borrowed heavily from Irish banks to try to shore up his position, and was eventually revealed to have debts of €195 million. In 2015, Allied Irish Banks (which had itself survived the wider crash only by dint of a state bail-out) took a hard line with O’Reilly, pursuing him to court for personal debts of some €23 million. This provoked sympathy not only from fellow tycoons such as Michael Smurfit, who called him “one of the icons of Ireland”, but also from some commentators who had previously mocked or vilified him.

One media executive noted that “for a man who was always acutely conscious of his standing in Ireland, it must be ironic that his years of wealth and power were less successful in securing popular esteem than being the victim of a big bad bank that has tried to humiliate him.” To no avail: he was declared bankrupt in a court in the Bahamas in November 2015.

Anthony John Francis O’Reilly was born on May 7 1936, the illegitimate son of John Patrick Reilly, a Dublin civil servant who added an “O’” to his name. Until he was 15 (when he was told by a priest at his school), O’Reilly had no idea that his father was in fact married not to his mother but to another woman by whom he had four children; he met his half sisters only at the funeral of his father’s wife in 1974.

O’Reilly was educated at Belvedere College in Dublin, a Jesuit school which numbered James Joyce among its former pupils. Although bright he was not a hard worker, but excelled on the rugby field where he acquired a reputation as a tall, fast, well-built centre. At 16, he was already playing for Leinster schoolboys and marked down as a potential future international.

In later life O’Reilly had few interests outside business, which consumed most of his considerable energies. During his years abroad he liked to describe himself as a “representative of Ireland” or, in more grandiloquent moments, “one of the new Elizabethans from Ireland”.

In 1976, he established the Ireland Funds, a charity which finances self-help projects north and south of the border to promote “peaceful and fruitful co-existence”. It was for this work that O’Reilly was awarded a knighthood in 2000 (Irish citizens may accept other countries’ honours with the approval of the Dublin government). Having previously styled himself “Dr” – he held a PhD in agricultural marketing – he attracted some hostility in Ireland, at a time when Anglo-Irish relations were still tense, for insisting on “Sir Anthony”.

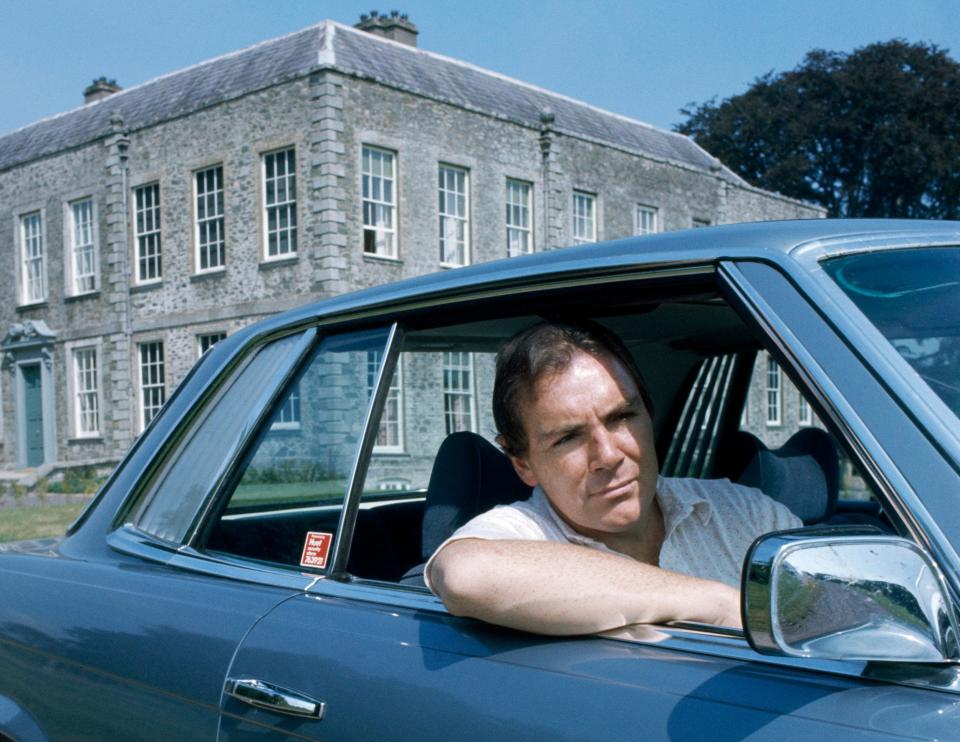

It was said that O’Reilly modelled the life of his large family on that of successful Irish-American dynasties such as the Kennedys. He created a “beach compound” at Glandore in West Cork (with two swimming pools, one for himself and the other for his guests) where the family spent every summer. He also kept a townhouse in one of Dublin’s finest Georgian squares, and in 1972 he acquired (from the Earl of Gowrie) Castlemartin, a grand mansion with a stud farm, 700 acres and a ruined 15th-century church which he rebuilt as the family chapel – and to which he moved his father’s remains from a public cemetery in Dublin.

It was at Castlemartin that O’Reilly was at his most Gatsby-esque, throwing lavish parties for celebrities, statesmen such as Henry Kissinger, Irish politicians and favoured members of his own staff. When the banks closed in on him, however, all O’Reilly’s major Irish properties had to be sold, along with an art collection said to have been worth €150 million. He and his second wife retained homes in the Bahamas and at Deauville in France.

O’Reilly married first, in 1962, Susan Cameron, an Australian by whom he had three sons (who all became executives in his businesses) and three daughters. The marriage was dissolved and he married secondly, in 1991, the Greek shipping heiress Chryss Goulandris, a noted racehorse breeder and chairwoman of Ireland’s National Stud, whose death in August 2023 aged 73 cast a deep sadness over his own final stage of failing health. He is survived by his three sons and three daughters of his first marriage.

Sir Anthony O’Reilly, born May 7 1936, died May 18 2024