Single-Cell Smackdown: The Battle for Earth's Early Oceans

Stromatolites ruled the fossil record for 2 billion years. The squishy, sticky mounds of communal-living microbes dominated shallow-water environments everywhere on Earth during life's early days. Then, long before algae-munching animals appeared 550 million years ago, stromatolites mysteriously plummeted in number.

Now scientists think they've found a possible culprit: another microbe called foraminifera. A billion years ago, these two single-celled species battled for supremacy in the world's oceans, and stromatolites lost, according to a study published May 27 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We'll never be able to prove what happened back in the Proterozoic, but we've at least shown there's a potential explanation," said Joan Bernhard, lead study author and a scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Mass.

Early ocean throw-down

Stromatolite mounds grow tall when waves cover the top layer of algae with mud or sand and a new algae layer covers the sunlight-choking sediment. The trapped sediments turn into distinctive rippled fossils. But the wavy layers disappear beginning about a billion years ago, replaced by thrombolites — clumpy, jumbled microbial mats.

Researchers suspect the decline is due to a change in ocean chemistry or the sudden appearance of a creature that found the stromatolites especially tasty — though there's no fossil evidence for this.

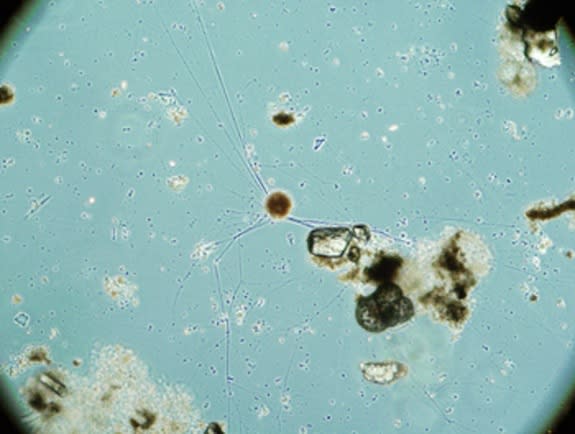

Bernhard said DNA evidence triggered her suspicion that forams (short for foraminifera) were guilty of turning stromatolites into thrombolites. Foraminifera are tiny organisms, usually the size of a sand grain, that grow hard shells. Their shells don't show up in the fossil record until just before the Cambrian period, about 550 million years ago. However, DNA evidence called a molecular clock suggests the first forams were shell-free, and evolved 400 million years earlier. (Without their shells, evidence of these early forams was less likely to survive in the fossil record.)

The rise of the forams thus neatly coincides with the demise of stromatolites, but a real-world test was needed to back up this idea. Bernhard and her colleagues collected modern stromatolites from the Bahamas, one of the few remaining spots where the microbial mounds survive today, and threw them in the ring with forams to see who came out the victor.

In this corner we have…

In a lab, the researchers seeded the stromatolites with forams from the same Bahamas bay. Ever so slowly, the foraminifera fanned out their hairlike pseudopods into the algae layers. Pseudopods help forams eat, move and explore their environment. After six months, the effect was devastating for the stromatolites. Their layers were scrambled. But during a control experiment, in which forams were treated with a chemical that kept them from using their pseudopods, the stromatolites were still pristinely layered at the end of the test. The team also found forams living in thrombolites from the Bahamas, supporting their hypothesis that forams turn stromatolites into thrombolites. [Stunning Photos of the Very Small]

Bernhard hopes to repeat the experiment with other single-cell species with billion-year-old ancestors, such as ciliates and flagellates.

"It's possible the foraminifera did this, but we certainly haven't resolved the question. It's an interesting one to keep studying," Bernhard said. "Foraminifera are often overlooked, but they are really diverse and they've been around for a long time. They may be a key player in a lot of Earth history," she said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.