Should we expand the Supreme Court?

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

In 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren helped craft a 9-0 decision in the landmark desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education, ensuring that this momentous change to American society would have the imprimatur of a united Supreme Court.

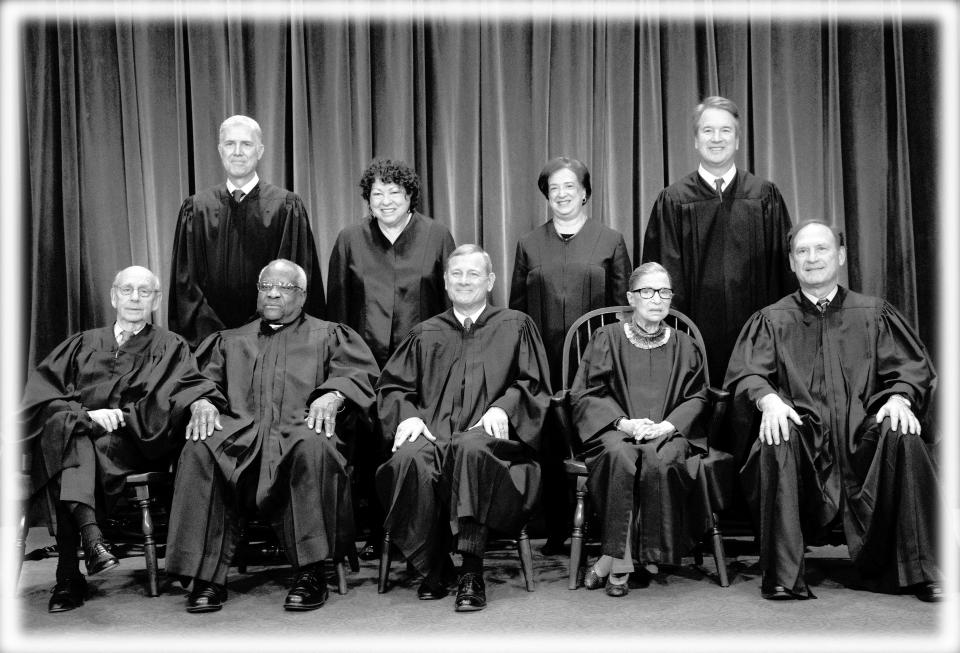

But it’s hard to imagine today’s rigidly divided, highly politicized court agreeing unanimously in an opinion on an equally controversial issue — abortion rights, for example. It has become commonplace to talk about “Republican” and “Democratic” justices, and to assume in advance that they will line up on any given issue with the party whose president nominated them. But sometimes — as with Donald Trump — the president was elected by a minority of the country, and while public attitudes change with the times, the justices often do not. With a 5-4 conservative majority seemingly locked in for decades to come, the court could find itself far to the right of the country on a number of issues.

During the tenures of Presidents Obama and Trump, the battles to confirm Supreme Court seats have become increasingly partisan, reaching a height when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refused even to consider the nomination of Judge Merrick Garland, who was chosen by Obama to replace Antonin Scalia in early 2016. Many Democrats consider that seat to be stolen, particularly after Republicans changed the rules to allow Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch to be confirmed with 54 votes in 2017, rather than the 60 that would have been needed to overturn a Democratic filibuster. Last October’s confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh was even more contentious and ended with a razor-thin vote of 50-48.

Commentators say a knockdown battle over every open seat is demoralizing for the country and cements the growing perception of the court as a political body.

The United States is the only democracy with lifetime appointments to its highest court without a mandatory retirement age. To Democrats, the possibility of facing a conservative majority on the Supreme Court for decades despite winning the popular vote in six of the last seven presidential elections is an outrageous injustice. “Given the Merrick Garland situation, the question of legitimacy is one that I think we should talk about,” said former Attorney General Eric Holder last month. “We should be talking even about expanding the number of people who serve on the Supreme Court, if there is a Democratic president and a Congress that would do that.”

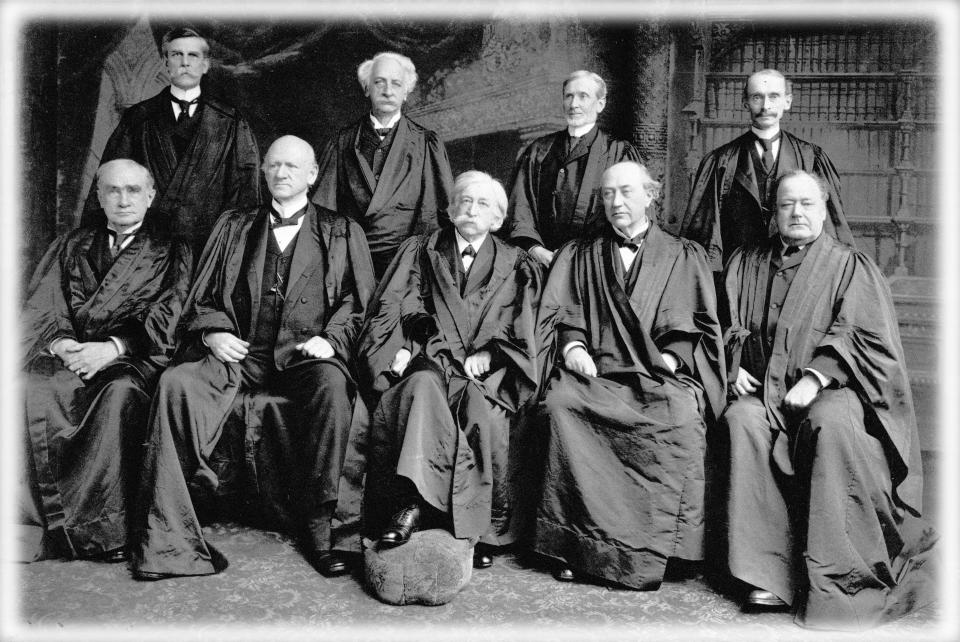

The Constitution is vague on the makeup of the court. It does not specify the number of justices, and regarding terms it says, “The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour,” which is usually interpreted to mean a lifetime appointment. The lifetime appointment aspect has stayed constant, but the number of justices shifted repeatedly over the first 80 years of the court.

Congress initially set the court at six justices with the Judiciary Act of 1789, before adding a seventh in 1807 to correspond with an additional appellate circuit. The number of justices was increased to nine in 1837, but that lasted only until the Civil War. During the war, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Northern judges who shared his aims of preserving the union and ending slavery, and Congress aided his cause in 1863, adding a tenth judge as the population in the California territories increased. But more extreme measures were considered.

“Lincoln and his party are talking about and entertaining all sorts of ideas in 1862,” said Tim Huebner, a history professor at Rhodes College who has studied the Supreme Court, “and one of the more radical ideas was to disband the entire court and start over. You would basically dissolve the court and give Lincoln an opportunity to appoint nine new justices.”

Following Lincoln’s death, Congress reduced the court to seven — with the blessing of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, who believed, mistakenly, that the move might increase the jurists’ salaries — so President Andrew Johnson couldn’t appoint any justices. After Johnson left office, Congress moved the number of judges back to nine in 1869, where it’s remained since.

The best-known instance of attempting to overhaul the court’s makeup dates to 1937, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, frustrated by rulings that struck down many New Deal programs, floated a plan to add as many as six more seats. Following his landslide 1936 reelection, Roosevelt proposed that justices retire after age 70. If they refused, a new "assistant" with full voting rights would be appointed, locking in a liberal majority. Before the bill was voted on, two justices who had been expected to be part of the conservative majority sided with the administration to uphold the National Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act, a maneuver that has gone down in history as “the switch in time that saved nine.” The “court packing” maneuver then died in the Senate.

Roosevelt’s gambit has been cited by Republicans who oppose adding justices.

“Some left-wing publications are already trying to lay the groundwork for, you guessed it, literally packing the court with more justices,” McConnell said last autumn on the Senate floor after Kavanaugh was sworn in. “That’s right, the far left has gone scrounging through the ash heap of American history, and they’re bandying about that discredited fantasy from the 1930s.”

There have been a number of Supreme Court reform proposals discussed over the years, but the one most often cited by Democratic candidates in this cycle has come from law professors Ganesh Sitaraman and Daniel Epps: “How to Save the Supreme Court,” which will be published in the Yale Law Journal later this year. Sitaraman, who teaches at Vanderbilt and previously served as Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s policy director, explained the two options outlined in their plan to Yahoo News.

The first is the Supreme Court Lottery, which would eliminate the nine permanent judges and instead rotate the approximately 180 appellate court judges for two-week stints via a random draw. The justices would hear oral arguments, make their rulings and select petitions for future panels to consider before being replaced by a new set of judges for the next round of cases.

The idea is that if justices are rotated among a pool 20 times as large as the current one, the battle over individual confirmations will become less intense. The plan, which has been floated by Sen. Bernie Sanders, would also be a throwback to the first century of the court, where until 1891 judges pulled double duty on both the circuit and Supreme courts.

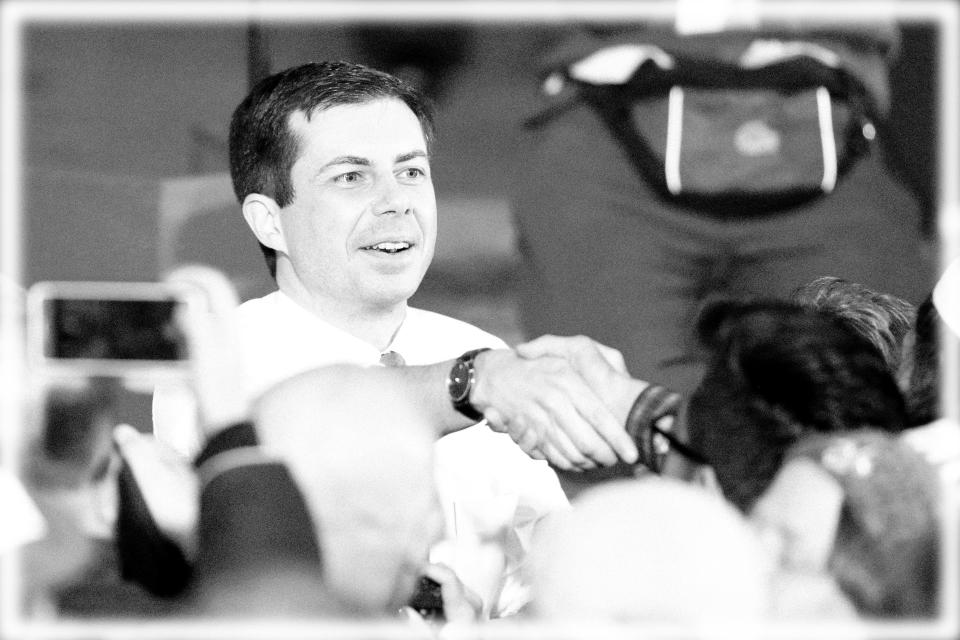

The second option, Balanced Court, has been touted by South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg. The plan would expand the court to 15, but attempt to do so in a neutral manner. Democrats would pick five justices, Republicans would pick five justices and then those 10 would work to unanimously select five more justices to round out the court. The thinking behind this plan is that appointing the swing-vote justices by their peers on both ends of the political spectrum will result in more moderate, independent voices. Former Rep. Beto O’Rourke has also said it’s a plan that should be explored.

Would either of the “How to Save the Supreme Court” plans hold up to legal challenges?

“Our goal is that these are not constitutionally bulletproof, but they are constitutionally credible and plausible arguments,” said Sitaraman, who added that the plans weren’t meant to be implemented together and instead should be seen as two separate options to consider.

Others have proposed term limits, usually ranging from 14 to 18 years, intending to make each nomination battle less contentious by regulating the number of appointments in each presidential term. It’s a policy that John Roberts, now the chief justice, supported in 1983. He wrote at the time: “Setting a term of, say, 15 years would ensure that federal judges would not lose all touch with reality through decades of ivory tower existence.”

Sitaraman cautioned against the unintended consequences of such a measure, noting that justices could potentially rule with an eye on a post-term career in lobbying in politics, while every presidential election could descend into a battle over Supreme Court appointments.

Adding justices to the court is the most straightforward approach, requiring a simple majority in Congress and a president’s signature. Imposing term limits would require a constitutional amendment, a process that hasn’t been completed in full since the voting age was lowered in 1971. One proposed way around needing an amendment would be for presidents only to nominate judges who agreed to step down after a set term, although there’s no obvious mechanism to enforce compliance with such a pledge.

“We don’t claim to have found the perfect solution,” said Epps, who co-wrote the proposal and teaches law at Washington University in St. Louis. “We’re less wedded to the exact details of our proposals than we are to the idea that we need to start thinking creatively about ways to design a Supreme Court system that at least makes some sense for the world we live in today and that doesn’t put too much power in the hands of individual people and make too much depend on what are seemingly random events.”

Considering McConnell’s work at locking in a conservative judiciary for decades to come, it is unrealistic to expect that Republicans will be interested in breaking their own hold on the system. This means it would be up to Democrats to both take the White House and find 51 votes in the Senate willing to change a system that’s been in place since the Ulysses S. Grant administration.

But some activists on the left are encouraged that there’s even a discussion: Besides Sanders, Buttigieg and O’Rourke, Sens. Warren, Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand all expressed an openness to expanding the Supreme Court in comments to Politico last month. In his messaging, Buttigieg initially tried to paint the move in nonpartisan terms but earlier this week referenced McConnell’s blockage of Garland as precedent

“It irritates me a little bit that every time I talk about a Supreme Court reform to make the institution less political, someone writes a gloss on it that makes it sound like I’m proposing that we simply add justices for the purpose of pulling the court further to the left,” said the mayor in an interview with Vox published on April 1. “Anything we do needs to be rooted in making sense in principle. And something that makes sense in principle is to protect the court from being the scene of an apocalyptic ideological fight every time the vacancy opens, and to set up the Court so that it has more people thinking for themselves.” in an MSNBC interview earlier this week, Buttigieg made the point that by blocking a replacement for Scalia, McConnell had in effect created an eight-person court.

“The Republicans in the Senate changed the number of justices on the Supreme Court,” said Buttigieg. “They changed it to eight, until they took power, and then they changed it back to nine. A lot of what we’re talking about is no less a shattering of norms than what the other side has done but we’re proposing to do it in a way that is more inclusive, I would say more constitutionally sound, more appropriate, and will just by the nature of the checks and balances in our system have to go through a very thoughtful and rigorous process.”

“Well, it’s not simply about adding to it in order to take it toward the left because it’s too conservative, even though I do think it is too conservative. We can’t go on like this, where every vacancy turns into an apocalyptic ideological battle,” he echoed himself in a recent New Yorker interview.

Critics of court packing have pointed to other countries where an expansion of the top court is seen as a way for an autocratic leader to consolidate power. If Democrats were to make a serious push at this, expect to hear Republicans cite Hugo Chávez’s 2004 expansion in Venezuela. (Hungary’s right-wing Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has also consolidated his power in the courts over the last few years.) There is also a concern that adding judges could just result in escalating constitutional hardball and potentially a delegitimization of the court, a scenario in which states begin ignoring rulings with which they disagree.

It’s also likely that Roberts would be a critic of the plan, as he’s attempted to defend both the legitimacy of his court and his eventual legacy as chief justice while pushing back on the idea that the court’s ideological divisions drive its opinions.

“We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges,” Roberts said last year. “What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

Unfortunately for Roberts, the current president has undercut his attempts at promoting neutrality.

“We’re going to have great judges, conservative, all picked by the Federalist Society,” Trump told a group of evangelical Christian leaders in 2016, referring to the conservative group that has focused for decades on moving the courts right.

“If it’s my judges,” Trump promised, “you know how they’re gonna decide, and if it’s [Hillary Clinton’s] judges, you also know how they’re gonna decide.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: