Why going online might be a futile strategy for department stores

As consumers spend more time online for their shopping needs, traditional department stores have aggressively reduced their brick and mortar presence while increasing their internet presence. But this might actually be a hopeless strategy as individual brands push for more direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales via their own websites.

“We’re seeing that manufacturers are trying to protect their brands,” according to Dennis Cantalupo, Chief Operating Officer at Creditntell, a retailing consulting firm. “This is putting more pressure on department stores, including their growing online businesses.”

Vendors from Michael Kors (KORS) and Coach (COH) to Ralph Lauren (RL) and Nike (NKE) have been pushing for more direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales, a move that directly undermines the best efforts of retailers like Macy’s (M) and Nordstrom (JWN).

Vendors are bypassing big stores and going directly to the consumer

It’s costly for vendors to push merchandise on the physical and digital shelves and racks of department stores. To compete, brands are often forced to employ aggressive promotional pricing (i.e. discounts) that eat into profit margins.

According to analysts, the DTC business model has become increasingly attractive. And now vendors are pulling back. Michael Kors (KORS) announced last August that it would reduce inventory in department stores and demand to be excluded from storewide promotions and coupons. Coach (COH) also announced last year that it would pull its products from more than 250 department stores, which reduces its presence by 25%. Ralph Lauren (RL) announced this month that it plans to reduce wholesale distribution.

Nike (NKE) said it plans to grow its e-commerce business from $1 billion in 2015 to $7 billion in 2020, three times the expected growth rate of the e-commerce industry. This is part of its broader effort to boost its DTC sales in that period from $6.6 billion to $16 billion. Nike’s DTC push comes at the expense of wholesale growth (to department stores), which is a shrinking source of revenue as seen in the UBS chart below.

Meanwhile, the company is building high-profile stores in urban centers, including in New York City.

Cowen’s John Kernan explained that these pushes come as the brands have experienced anemic growth within broader stores. For example, Nike and Under Armour (UAA) sales growth per store at Dick’s Sporting Goods (DKS) were 1% year-over-year in 2016 compared to a prior three year average of 6% and 11%, respectively.

This broad shift of vendor efforts to move away from wholesale has already been felt at sports good retailers Dick’s and Foot Locker (FL), whose latest disappointing reflected the increased pressures.

“We understand why the broadened distribution has happened and what’s going on,” Dick’s CEO Edward Stack said on the company’s recent earnings conference call. “We don’t really like it, but we understand that. And that’s the way of the world…I think it’s just the perfect storm right now in retail, and I think sporting goods is in the center of it right now.”

Of course, not every brand can just open its own store.

“Nike has the firepower and will to generate enough interest outside of traditional channels,” UBS’ Michael Binetti said.

Department store websites could become showrooms

Meanwhile, as individual vendors are upping their DTC presence, Amazon is flexing its muscles to be more of an online destination for multiple brands. In June, the e-commerce giant inked a deal with Nike to sell shoes directly through a brand-registry program.

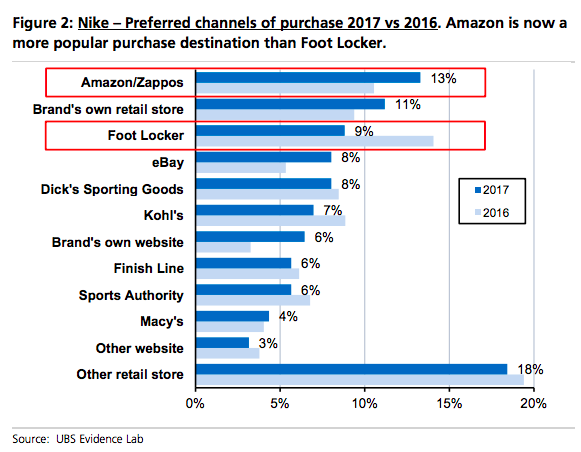

And Amazon is now the preferred channel for Nike purchases, followed by the brand’s own retail store. Retailers that sell a house of brands, like Foot Locker and Dick’s Sporting Goods have become less popular.

And while other brands may not have Nike’s fire power, the value proposition of multi-brand retailing at department stores is becoming challenged.

The lingering question is the sustainability of department store promotional events, according to analysts, particularly given the pressure on margins and reluctance from vendors to participate in discounts.

“Department stores may have to re-invent themselves,” Cantalupo said. “Their websites [could] ultimately become show rooms for shoppers to browse before going directly to a vendor’s site. But the bigger concern would be what would the department store do with all the retail square footage if we did see an even more accelerated shift towards online sales?”

In the meantime, the best-positioned names outside of Amazon currently are ones that have been able to offer a differentiated in-store experience with less online reliance. Off-price names, like TJX (TJX) and Ross Stores (ROST) that emphasize their treasure-hunt in store have also soared despite a limited online presence. And Home Depot (HD), which draws consumers into stores via its order-online pickup in store option and superior execution has also been rewarded by shareholders.

Ultimately, the department stores are being left in a difficult spot, squeezed by the rising power from the vendors they carry on the one hand and the online prowess of Amazon on the other. Whether or not they can remain “destinations” in person and online in the coming years will be paramount to their long-term sustainability.

Nicole Sinclair is markets correspondent at Yahoo Finance

Please also see:

Digital ads aren’t working for big consumer brands

Why Home Depot is leaving Lowe’s in the dust quarter after quarter

Walmart’s sales numbers make Amazon look small

HomeGoods is the most impressive retail story in America

Why Nordstrom is beating all of its department store competitors