Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation eyes opening Labrador's first accredited residential treatment centre

Sixteen Innu stood in front of family and friends, giving short speeches after graduating recently from Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation's first residential addictions treatment program at a former Christian Youth Camp.

"Here is where I find my identity, here is where I started to find connection with the earth," said program graduate Mary-Charlotte Michel at the Feb. 29 ceremony.

The first group of graduates is just the beginning of the First Nation's plan for the camp and Labrador as a whole.

Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation is working to create Labrador's first nationally accredited residential addictions treatment program, to help all Labradorians seeking help for addiction.

It would mean people struggling throughout the region would be able to stay close to home, rather than the current practice of travelling to Newfoundland or Ontario.

"The vision is to not only help the Innu but everybody else," said Mishan Nuna, a Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation addictions worker.

"But this is a huge start for the community of Sheshatshiu, to [move] in the right direction."

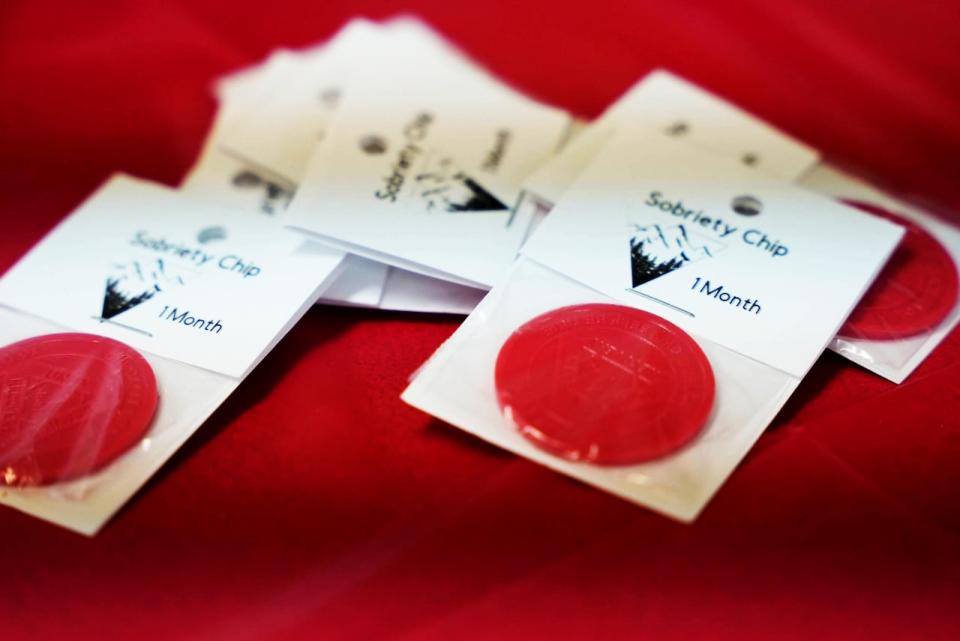

Mishan Nuna, a Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation addictions worker, says he's proud of the graduates who are celebrating one month sober and says support will be there to help them in the future. (Heidi Atter/CBC)

The program can help only its own First Nation members right now but could take in people from anywhere if accredited, Nuna said. Helping all of Labrador was his dream from the beginning, when he started working in addictions 10 years ago, he said.

"Addiction, when you think about it, doesn't only attack the Innu, doesn't matter what gender, what age and so on," Nuna said.

Indigenous Services Canada said it is aware that Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation has purchased the former Christian Youth Camp and intends to provide a residential addictions treatment program.

In a statement, the department said it's committed to supporting Innu self-determination in health care, including in Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation. To become accredited, Sheshatshiu needs to be evaluated by a third-party accreditation body.

"We will be there to support the community, at their request, to help them navigate the accreditation process," the department said.

The government of Newfoundland and Labrador said it's aware of the plans and will work with the organizers as it's developed. The province said it's also providing funding to support culturally informed, land-based programing as part of its suicide prevention plan.

22 people died in past 2 years due to addictions

For years, Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation ran a residential treatment home called Apenam's House in North West River. The program was a continuous intake but had to be closed after the building was declared uninhabitable.

Since then, the First Nation worked to buy then fix up the closed Christian Youth Camp along the highway between Happy Valley-Goose Bay and Sheshatshiu. The first residential program began in February.

The need continued despite the program taking a break, Nuna said. Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation said 22 people have died due to complications related to addictions, including suicide, in the past two years.

It's important to have a residential program because it allows people to stay with others, immerse themselves in the programming and have a higher chance of following through, Nuna said.

It's also key to have culturally relevant programming, especially in Innu-aimun, Nuna said.

"We all know how to speak English, but when we come to a program like this, we have to share with our feelings. And with our feelings comes naturally within our Innu-aimun," Nuna said.

"That's the biggest thing I think for this program and so how amazing and how proud they are in speaking their language still."

The former Christian Youth Camp outside Happy Valley-Goose Bay was bought by Sheshatshiu Innu First Nation and now hosts an Innu-led addictions treatment program. (Heidi Atter/CBC)

Michel said she needed the program after losing four people close to her to suicide in the past year.

"It's been a really hard journey. Very hard journey. But for the grace of God, we have this program starting up again," Michel said. "It just goes to show that the people really wanted this back."

It was at the program that Michel learned about intergenerational trauma and could see how being a residential school survivor manifested in her mother and the hurt people throughout her family suffered, she said.

Mary-Charlotte Michel says the treatment program taught her about herself and her mother and family. Her mother came to her graduation. (Heidi Atter/CBC)

"This place is a perfect place to heal and understand that intergenerational trauma is what is affecting our community," she said. "The drugs, the usage of alcohol, gambling, you know, stuff like that. And this is the perfect place to start our community with healing."

Now a program graduate, Michel hopes to work in addictions in the future to help others heal, she said. She also hopes to remember and honour those who have died.

All program graduates received a new one-month sobriety chip. (Heidi Atter/CBC)

Nuna hopes all the graduates today will continue on their new path, but that there will be support in the future to help them stay healthy, he said.

"I always spread the message that this is not a finish, it's a start. It's a start to live in a new way of life."

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.