She hasn’t charged a cop for a fatal shooting in 27 years. Amid protests, election nears.

The statistic has been chanted at rallies, printed on fliers and posted on tweets: During 27 years in office, State Attorney Katherine Fernández Rundle has never charged a cop for a fatal shooting while on duty.

Since 2016 alone — the year she was last reelected without opposition — 73 police shootings, fatal and non-fatal, have come up for review before her office. Fifty-four are closed. Eighteen remain open. Just one resulted in a criminal charge, a trial that ended in the misdemeanor conviction of a North Miami cop who shot at an autistic man holding a silver toy truck.

Her office has charged plenty of officers for other crimes. But as protests against police brutality have unfolded across the United States, and Fernández Rundle seeks an eighth full term as Miami-Dade’s top law enforcement officer, her record on police shooting cases and in-custody deaths has emerged as the central theme of the campaign. Election day for the primary is Aug. 18.

The Black Lives Matter movement has also cast scrutiny on Fernández Rundle’s relationship with Miami-Dade’s Black community, and resurrected old tensions between the Democrat and her own local party, which publicly called on her to resign three years ago over her decision not to seek charges in the case of a mentally ill prison inmate who died inside a locked, steaming shower.

“If you’re not going to charge the cases, you’re never going to know if a jury would have convicted,” said her lone opponent, Melba Pearson, a fellow Democrat who is running with hopes of becoming Miami-Dade’s first Black state attorney. “Every shooting is not a justified shooting. There has to be that political will to be like, ‘Listen, some of these cases need to go to the jury. You may lose some of these cases. It doesn’t mean it was wrongfully filed.”

Fernández Rundle defends her record — pointing out that up until two recent cases, no state prosecutors in Florida had charged an officer in a fatal shooting while on duty since 1989.

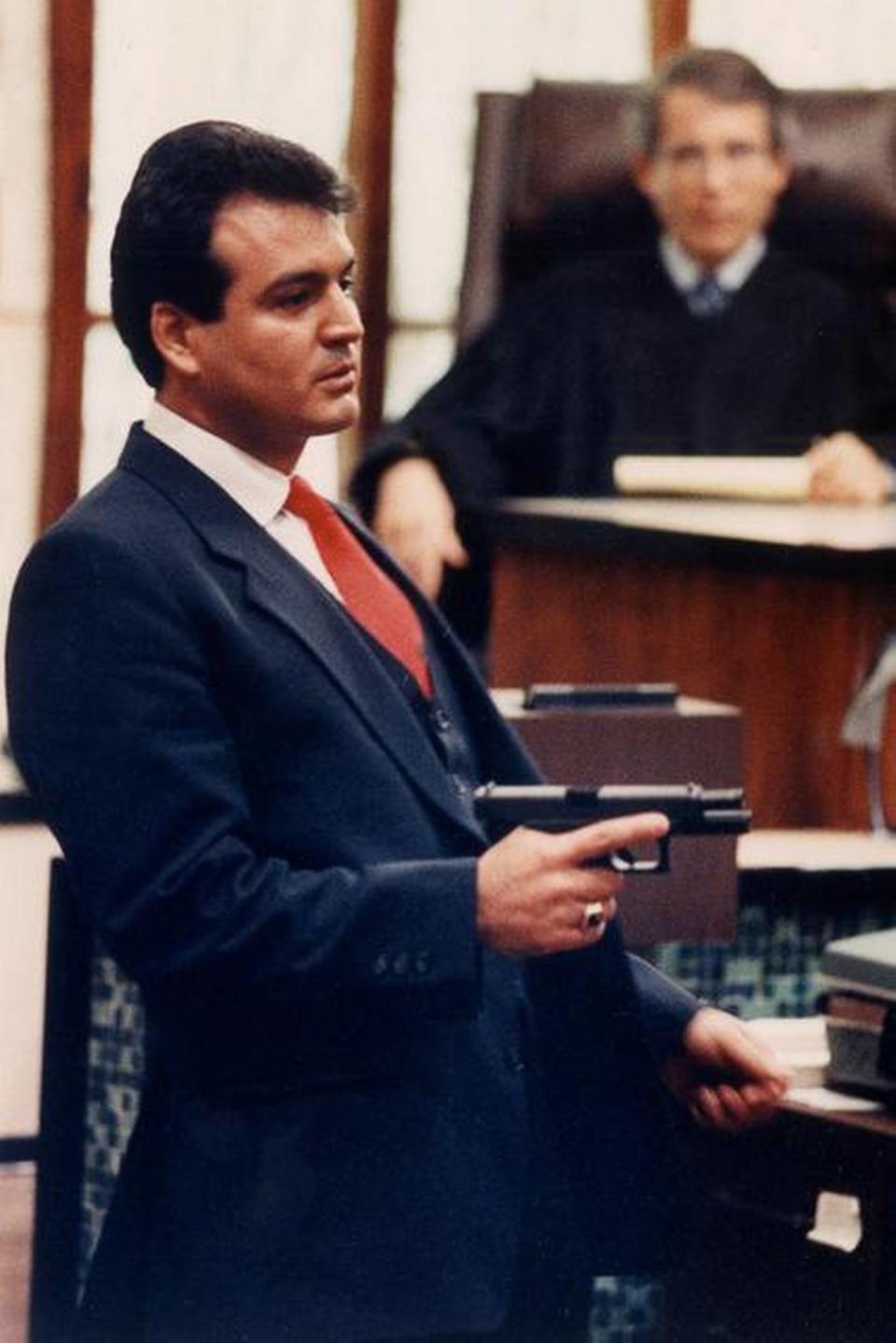

The reason: Florida law has long allowed wide leeway for officers to use deadly force, even allowing a cop to shoot someone suspected of a felony in the back. Appellate case law, stemming from the ultimately failed prosecution of Miami Police Officer William Lozano for a 1989 fatal shooting, also limited how much prosecutors can show cops ignoring their own internal department policies.

She acknowledges that there is “something wrong with the law,” but insists that her ethical duties prevent her from prosecuting without enough evidence.

“A lot of people say, ‘OK, just do it anyway, just try the case anyway,’” Fernández Rundle said. “Are we going to do that for everybody? Teachers, doctors, nurses? Our obligation says we’re not permitted to do that, and it applies to police officers as well. We can’t just take our best shot.”

She added: “We know we’re an easy target. We understand, but it needs to be seen in the bigger context.”

Long History in Miami

Fernández Rundle, 70, is among the best-known politicians in Miami. She served as a high-ranking prosecutor under predecessor Janet Reno until 1993, when Reno left to become the U.S. Attorney General under President Bill Clinton and then-Gov. Lawton Chiles appointed her to take Reno’s place, making her Florida’s first Hispanic state attorney.

Two years ago, she flirted briefly with the idea of running for governor or attorney general. Her long tenure is not unusual among elected state attorneys — Broward State Attorney Mike Satz is stepping down in November after 44 years in office, and Miami-Dade had only ever had three: Fernandez Rundle, Reno and the first, Richard Gerstein, who was elected in 1956 and served six terms.

That notoriety has its benefits and downfalls. Now seeking to enter her fourth decade as Miami’s top prosecutor — a job paying $170,000 a year — Fernández Rundle has raised about $500,000 in campaign cash and is as entrenched as any incumbent in Florida. Hoping to enter her fourth decade as Miami’s top prosecutor, she has a net worth close to $4 million.

But she is also the focus of boiling-over frustration regarding policing and criminal justice, with protesters frequently using her image and office as a symbol of outrage and injustice.

“She has not prosecuted police officers for an on-duty [fatal] shooting in my entire lifetime,” Jorge Damian de la Paz, 28, said during an early June protest outside Fernández Rundle’s office. “It’s egregious. This has to change.”

Police are rarely prosecuted in Florida for shootings. And Fernández Rundle has been around long enough to be challenged from the left and the right, surviving politically through three decades thanks in part to shifting alliances.

Twenty years ago, her first serious opposition was posed by Al Milián, a former police union lawyer backed by the powerful Miami-Dade Police Benevolvent Association. The union alleged Fernández Rundle was soft on crime. She insisted it was payback for her tough stance on charging cops. “They ran someone against me because I prosecuted their friends,” she said at the time.

Fernández Rundle trounced Milian by 11 percentage points. Milian captured 80 percent of the Hispanic vote, but Fernández Rundle rolled to victory with a whopping 93 percent of the Black vote and a large percentage of white non-Hispanic votes.

Since then, her standing among Miami’s Black voters has wobbled, due in part to the prosecution of popular Black politicians. Fernández Rundle was one year removed from the failed bribery prosecutions of Miami Commissioner Michelle-Spence Jones, the city’s lone Black commissioner, when Rod Vereen, a veteran African-American defense lawyer, mounted a challenge in 2012.

Fernández Rundle won more than 60 percent of the vote, cruising to victory in a Democratic primary. No Republican challenged her.

This spring, Miami’s top prosecutor again appeared vulnerable, as Pearson, a former deputy director of Miami’s American Civil Liberties Union who spent 16 years as a prosecutor under Fernandez Rundle, mounted a campaign based on criminal justice reform and protests broke out across the country.

Pearson said the Black community is upset over disparities in how they are treated. Pearson’s supporters have been pointed, even calling Fernandez Rundle a racist. Pearson doesn’t go that far.

“I don’t think she’s a racist. But I do think you can be a tool of white supremacy without intending to be. You can withhold certain structures that end up oppressing other people,” Pearson said.

But Pearson’s campaign is strapped for cash. And due to a quirk in Florida law, Republican and independent voters will be able to participate in the Democratic primary between Pearson and Fernández Rundle, diminishing the threat of being outflanked on the left. Political analysts expected Pearson to recruit someone to “close” the primary to only Democrats by filing as a write-in candidate. But that didn’t happen.

Tangela Sears, a prominent Black Miami activist who runs an organization for families of murder victims, said she believes Fernández Rundle still remains popular with Miami’s older Black establishment after years of appearing at community forums, doing radio spots and forging relationships with African-American clergy.

“Yeah, we have concerns but Kathy has worked hard for the Black community. She has always been a friend to the Black community,” said Sears, who blames Florida law for the lack of cops arrested in force cases. “She had to make tough decisions from time to time ... “If Melba comes to be the state attorney, she’d have to make the same decisions.”

National Scrutiny

The spotlight may be hotter now — and amplified by social media — but the criticisms of Fernández Rundle’s handling of police use-of-force cases stretch back decades.

Many of the cases have long ago faded in the public memory, like the 2001 fatal shooting of Alphaeus Dailey, a wheelchair-bound paraplegic shot in the back after a North Miami Beach police officer said he pointed a gun at him from over his shoulder. The shooting led to rallies, a town hall meeting and sharp criticism from Dailey’s family, but ultimately, prosecutors ruled the officer was justified.

In another high-profile case, her office declined to press charges against Miami-Dade police officer Jorge Espinosa after he shot an unarmed teenage burglar, Leonardo Barquin, as he ran away in 2004. The case took five years to investigate, spurred a whistle-blower lawsuit by a disgruntled prosecutor and drew the ire of the dead teen’s family. In the end, her office declined to rule the case justified but determined there wasn’t enough evidence to overcome Florida’s “fleeing felon” law.

She also got into a public spat in 2010 with then-Miami Police Chief Miguel Exposito, who criticized Fernández Rundle about the inordinate amount of time it takes to close shootings. The Miami Herald reported in 2011 that there were still 63 unresolved police shootings, stretching back over a decade.

More recently, Fernandez Rundle’s office came under scrutiny for not pressing charges on any of the Miami-Dade police officers who shot and killed four armed robbers in a reverse sting in Redland in 2011. Killed in the attack was a confidential informant, Rosendo Betancourt, 39, who had already surrendered when he was shot by a police sergeant.

Prosecutors wrote a scathing report pointing to severe flaws in the operation and finding that many of the officers’ actions were “unusual, counter-intuitive, suspicious . . . disturbing.” But as for the killing of the informant, prosecutors said they could not disprove the sergeant’s claim of fear because Betancourt appeared to be reaching for his waistband.

In 2011, citing the fleeing felon law, she also declined to file charges for officers who fired over 100 bullets at a car that nearly ran over bicycle cops on a crowded South Beach street. The death of driver Raymond Herisse angered many as it came during Memorial Day celebrations that have frequently revealed tensions between young Black visitors and police.

Fernández Rundle’s handling of one particular high-profile case — the death of Dade Correctional Institution inmate Darren Rainey from inside a hot shower rigged by prison officers — has become a rallying cry for Black Lives Matter protesters marching through the streets of Miami. She declined to charge any officers because the Medical Examiner determined he suffered no burns.

The case soured her relationship with the Miami-Dade Democratic Party, which unanimously passed a resolution three years ago calling on her to bring charges in the case or resign. “This follows a pattern over Rundle’s ... tenure as Miami-Dade’s elected state attorney in which she has repeatedly refused to hold law enforcement officials accountable for on-duty killings,” the resolution stated.

Steve Simeonidis, the current chairman of the Miami-Dade Democratic Party, said the party has not changed its stance since the resolution passed unanimously on June 21, 2017. “The resolution speaks for itself,” he said.

Recent Record

Fernández Rundle says she’s not fazed by the criticism, even from within her own party.

As her successes, she points to Miami-Dade’s low crime rate, programs embedding prosecutors in high-crime areas, increased efforts to combat human trafficking and efforts to oppose Florida’s controversial Stand Your Ground self-defense law. She also succeeded in giving out raises to prosecutors amid an exodus because of low pay, and helped establish a “rocket docket” to help former felons restore their right to vote following the passage of Amendment 4 in 2018.

This month, Fernández Rundle publicly backed support of an independent civilian review panel for Miami-Dade police. In Downtown Miami, she joined a rally calling for an end to racism, marching alongside pastors and other community leaders — including Sybrina Fulton, the mother of Trayvon Martin, whose death eight years ago at the hands of a neighborhood watch volunteer also sparked national conversation about race and justice.

Fulton, however, isn’t sold on Fernández Rundle.

“I know one thing, there hasn’t been a police officer arrested or charged with killing an African-American in Miami-Dade County in 27 years and that’s a concern,” said Fulton, who is running for a Miami-Dade County Commission seat representing Miami Gardens and Opa-locka. “Is that a record they’re trying to maintain? Who’s policing the police?”

Fernández Rundle insists she is. The prosecutor points out that under her watch, hundreds of police officers have been arrested for other misconduct cases, everything from pocketing money in drug deals to rapes. Her public-corruption section also worked with the federal counterparts to arrest a group of Biscayne Park cops for framing Black men for crimes.

Her office has also charged a slew of cops for slaps or kicks during arrests, the latest a Miami Gardens police officer accused of putting his knee on the neck of a woman in January. Her office, however, has lost three excessive-force cases at trial.

As states across the country grapple with law enforcement tactics, Fernández Rundle says she advocates tweaking the state’s “fleeing felon” law, narrowing which felonies might justify killing a fleeing suspect. She says she also supported a Democratic-sponsored Senate bill last year that would have limited police use of deadly force, a measure that failed.

“We believe there are reforms needed,” Fernández Rundle said. “Now, there seems to be a real will to take things to another level.”

That’s not enough, said Billy Corben, a Miami documentary filmmaker and vocal critic who recently released a video blasting the state attorney. He said Fernández Rundle rarely considers charging cops in fatality cases with lesser crimes such as perjury, and has spent decades not using her pulpit in Tallahassee to lobby for changes to use-of-force laws.

“She has never taken it seriously,” Corben said. “She can’t complain about it on one hand, and then do nothing with her power to change it.”