Sex, Love, & Marriage Behind Bars

I first heard about the trailers, prison vernacular for conjugal visits, on Rikers Island. It was 2002, I was twenty-four, and I was awaiting trial on murder charges. The guy the next bunk over in the communal dorm knew I was facing a lot of time, even if I didn’t know that. I was delusional in the beginning. We all are.

The bunkmate had just finished a dime—a ten-year sentence—for assault and was now in on a parole violation for breaking curfew, caught on a tip called in by his wife. Still, he loved her, and he loved telling me about going on conjugals with her up in Auburn, a maximum-security prison. It wasn’t just about the sex, he said. It was forty-eight hours of freedom, or close to it. Most of New York’s maximum-security prisons had them. They weren’t trailers, not anymore, but modular homes. He described the units: two, sometimes three bedrooms—the prison supplied pillows, bed linens, towels, and washcloths—a living room, a bathroom, and a full kitchen stocked with pots and pans, a coffee maker, a blender, and utensils. A wire bolted to the counter next to the sink was connected to the handle of the kitchen knife. His wife would bring clothes, cosmetics, and groceries: milk, eggs, pork chops, shelled shrimp. Glass containers weren’t allowed; neither was alcohol, not even as a makeup ingredient. Outside there was a picnic table, a barbecue pit, and a children’s play area.

It was, the fella in the next bunk told me, an opportunity for good times, good eating, and good sex. An incentive to stay out of trouble in the hope of experiencing a touch of love.

There was a hitch: Your partner had to be your legal spouse. Close family members were also eligible, of course, and this was really the objective of these visits: to build and maintain better family ties. But that was beside my bunkmate’s point. If I was convicted, he said, he recommended I put an ad on one of those prisoner dating websites (Prison Pen Pals, Write a Prisoner), find a woman, fall in love, make it official, then head for the trailers.

In 2004, I was sentenced to twenty-eight years to life. The minimum was longer than I’d been alive. Early on, I didn’t think much about the implications for my love life. At twenty-four, I’d had plenty of sex but never a real relationship, or even healthy intimacy. Besides, there were more pressing concerns: appealing my conviction, learning how to survive in this place.

I first saw the trailers at Clinton Correctional, a maximum-security prison a few miles south of the Canadian border, in Dannemora. By then I’d learned that New York’s Department of Corrections and Community Supervision didn’t actually call them conjugal visits. Only Mississippi did. While the word conjugal simply means “related to marriage,” these visits began to carry lewd implications, and other states opted to rebrand: In California, it was known as “family visiting.” In Connecticut and Washington, they were referred to as “extended family visits.” In New York, it was, and still is, called the Family Reunion Program, or FRP.

In 2005, I had my first FRP visit—with my mother and my aunt. My aunt cooked bacon and eggs in the morning, grilled porterhouse steaks and tossed salads for dinner. We sank into the soft couches, ate, and watched Law & Order reruns, oddly Mom’s favorite show. We talked until interrupted by the muffled screams of a couple through the wall of the attached unit. We laughed awkwardly, avoiding eye contact, and I felt kind of jealous. Three times a day, a phone in the unit rang. I picked up, spat my last name and identification number into the receiver, then stepped outside and waved to the watchtower guard. That count was one of the only reminders of prison.

When I returned to my block, guys asked how the conjugal had gone. Great, I said. When I mentioned it was with my mother and my aunt, they sort of nodded, like, Oh, that’s cool, too. I loved visiting with my family. But I did start to think about what it would be like to be with a woman again.

I got by with my hand and my memories, with the occasional assist from Buttman or High Society. Many of us who’ve been locked up all these years try idiosyncratic methods to pleasure ourselves. Some use a Fifi—a rolled towel with a plastic bag stuffed in the crevice; inside the bag is a rubber glove lubed with Vaseline that can be warmed in a hot pot of water, if one prefers. The crevice can be tightened or loosened by a strap wrapped around the rolled towel, creating different sensations. Fucking Fifis was an intimate ritual for one of my neighbors. At night he hung a curtain across his cell bars, prepped his Fifi, rolled the whole thing up in his mattress—he said it was more like a big-booty girl that way—laid out a few porno mags, and started thrusting.

But I wasn’t looking to hump a Fifi for the next twenty-five years.

Married men in the joint who went on conjugals seemed to have the most meaningful lives: They worked out, they went on visits, they sported crispy new sneakers and polo shirts with the horse, as if to say to the rest of us, I got a lady who loves me, and I got more status than you. At least, that’s how I took it. Every few months, they disappeared—most men kept their conjugal dates to themselves to avoid attracting envy—but we all knew where they’d gone. They came back to the cellblock with hickey-covered necks, looking pleasantly tired. I decided that was how I wanted to serve my sentence.

Mississippi State Penitentiary, of all places, was the first facility in the U. S. to offer conjugal visits, in the early 1900s. Also known as Parchman Farm, the segregated prison functioned as a revenue-generating plantation that produced cotton, cattle, pork, and more; its prisoners performed all the hard labor. To incentivize their work, administrators began arranging for prostitutes to visit on Sundays, and prisoners slept with them wherever they could—tool sheds, storage areas, the barracks. At first, only Black prisoners were allowed to participate, and for deeply racist notions “about Black men’s allegedly voracious sexual natures and appetites,” says Heather Ann Thompson, author of the Pulitzer-prize-winning history of the Attica uprising, Blood in the Water, “that Black prisoners could be forced to work even harder not just under threat of the lash but also, due to their savage nature, the promise of sex.”

Starting around 1940, all of Parchman’s prisoners were able to participate, regardless of race. By the late fifties, prostitutes were banned, replaced by prisoners’ spouses, common-law wives, and female friends. In 1972, the program opened to the facility’s female prisoners. Still, the system was marked by prejudice. “The most important question concerning a program of conjugal visiting,” wrote Columbus Hopper in his 1969 study of Parchman, Sex in Prison, “is whether it helps to reduce the problem of homosexuality in prison.” Hopper was the leading conjugals researcher of his time, and the “problem of homosexuality” seems to have been one of the main forces behind his advocacy. Truth is, in my twenty-one years of incarceration, I’ve never been sexually assaulted or witnessed that kind of assault.

New York’s first FRP began in 1976, with five 12-foot-by-70-foot trailers in a former cow pasture at Wallkill Correctional. Attica got its trailers in 1977, six years after the prisoner uprising for more humane treatment that, when law enforcement took back the prison, left thirty-nine dead. In the first eighteen months of Attica’s FRP, 1,179 prisoners participated.

By 1993, seventeen states allowed some version of extended family visits. That year in New York, 12,401 family members attended FRPs across the state. “The effectiveness of the program is beyond dispute,” the prison commissioner wrote in an op-ed around that time.

Data supports the former commissioner’s claims. According to a recent literature review, prisons that allow conjugal visits have better disciplinary records than those that do not. What’s more, studies have determined that released prisoners with an established relationship have a much better chance of not returning to prison. (In 1980, New York’s corrections department published findings suggesting that participation in the program decreased recidivism rates by as much as 67 percent.)

Yet since the start of such programs, fierce resistance has followed. By the early nineties, the era of mass incarceration was fully under way, and across the country, prison programs that incentivized good behavior—furloughs, work release, college, conjugals—were on the chopping block. Why, the thinking went, should we coddle criminals with taxpayer money? (It’s worth noting that FRP upkeep is paid for in part by prisoner fundraisers.) And don’t conjugals present one more way to introduce contraband?

As early as 1969, when Hopper published his findings on Parchman, conjugal visits were available in Chile, Ecuador, Japan, Mexico, Costa Rica, and the Philippines. Today, that list includes Qatar, Argentina, Brazil, Belgium, Sweden, Spain, France, Russia, and Saudi Arabia.

This article appeared in the Winter 2022/23 issue of Esquire

subscribe

The United States has shifted in the opposite direction. In the eyes of the law, conjugal visits are a privilege, not a right. The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld prison administrators’ latitude to limit prisoners’ rights, including visitation, writing in 2003 that “freedom of association is among the rights least compatible with incarceration.” In 2014, Mississippi did away with its program. “There are costs associated with the staff’s time,” the state’s prison commissioner said at the time. “Then, even though we provide contraception, we have no idea how many women are getting pregnant only for the child to be raised by one parent”—as if such family planning were his call to make.

Today, only four states allow conjugal visits—New York, California, Washington, and Connecticut—though when Covid came, Connecticut’s program was suspended, and it has yet to return. Federal prisons don’t offer the privilege. New York’s program has been a success: FRP is offered at twelve of its fifteen maximum-security prisons and eleven of its twenty-six medium-security prisons. Since 2011, same-sex couples have been able to participate. Yet each year over the past decade or so, Republican state senators have introduced a bill to eliminate FRP. Conservatives preach the importance of a solid family structure. Why would they want to sabotage prisoners who are trying to build and maintain theirs?

By 2009, I was in Attica; my appeals had been denied. I was thirty-two and lonely. I’d spend hours each day watching the tiny TV in my cell. The Bachelor was my favorite show—a glimpse of intimacy, however stage-managed, and a break from my bleak reality. I felt like I was squandering an opportunity by not putting myself out there. I told Mom what the guy on Rikers Island had suggested, and she put an ad on the prison dating website Friends Beyond the Wall.

Danielly was a year younger than me and lived with her teenage son in a housing project on the Lower East Side. “I’m Dominican, and brown. Do you like that?” she wrote. Yes, yes, I loved it! In an early letter, I brought up the trailers, told her to imagine an uninterrupted weekend together in a sort of cabin, no cell phones, no distractions—just us. She didn’t need to be sold. Her mom had married a guy who’d done time, she told me, and she remembered visiting those little homes in the prison as a young girl.

Danielly started visiting me at Attica. She was my type—curvy, full of attitude and affection. We had the kind of chemistry that made my stomach flutter. But I soon learned that my type was much harder to handle on the inside than it had been when I was on the outside. The guy she’d described as her ex-boyfriend was more like her current boyfriend. When I called her, she sometimes wouldn’t answer. I was left lovesick, and that’s no way to live in prison. So I let her go.

In January 2011, I started corresponding with Raina, a California blonde, thirty-nine, who’d never been married and had no kids, and it wasn’t a dealbreaker that I’d killed a man. She had a great sense of humor, and while she’d known darkness in her own life, she’d needle anyone who took theirs too seriously. I was hooked. She was emotionally intelligent, we spoke the language of recovery, and our relationship felt safe. She moved across the country for me. One day in 2012, in Attica’s visiting room, I proposed to her, and she said yes. Six months later, we joined a few other couples in a small room with a Goofy mural painted on the wall and Attica’s town clerk seated at a table, and we got married.

By 2014—after a series of applications, denials, appeals, and interviews, including one in which Raina was told I didn’t carry any sexually transmitted diseases—we had our first FRP date.

Two days beforehand, I had to piss in a cup under a guard’s gaze for my drug screen. Then again the day of, and again after I came off the trailer. Most of the work was on Raina: shopping, traveling, then getting processed, food pushed through an X-ray machine, gloved fingers sifting through her panties and K-Y jelly.

The corrections officer escorted a handful of us through the Attica lobby, a part of the prison I had never seen before. Gates opened and closed, and we walked to the FRP compound. A fence enclosed the five red-sided homes, situated so that the rest of the prison couldn’t see in. Though the watchtower guard kept a close eye.

Sitting on the couch, looking around, I felt . . . joy. In the system, you’re always waiting, and never for anything good: trial, sentencing, transfers, getting cuffed and shackled, always in a cell or a bullpen or on a bus eating bologna sandwiches. Now I didn’t know what to do with myself, and I loved it. I got up from the couch, turned on the stereo, then walked outside on the grass, sat on the children’s swing, went back inside. I grabbed the remote, turned on the flat-screen television, flipped through the stations. To do whatever I wanted, and to be waiting for my wife so we could do whatever we wanted—I felt giddy. Through the window I watched my neighbor in his kitchen as he boiled the silverware—forks, (butter) knives, a spatula, a ladle, all metal and engraved with tracking numbers—in one pot of water, and added a few drops of scented oil to another, to perfume the place. Finally, I heard one of the guys yell, “They’re here!”

A corrections van with blue-tinted windows pulled up, and the family members got out. A little boy ran to his father and jumped in his arms. And there was Raina. The CO let me help her with her luggage, which was in a container marked with our unit number.

As soon as the door of our unit closed, we threw the groceries—including cuts of filet mignon and A.1. sauce—on the table and started awkwardly kissing. As we began to undress, there was a knock on the door. Raina put on a shirt and I cracked the door. It was the CO, who just needed our container. It was like that, the conjugals; they were such a departure from regular prison life. Even the staff interactions were all good.

Raina and I got back to it. It was my first time in eleven years, so I figured I’d finish fast. But it was the opposite. We went at it for a while—soft, hard, slow, fast, this way, that way—and nothing seemed to bring either of us closer to climax. It was like I’d never touched a woman before. It felt weird that nobody else was watching us. I eventually pulled out and brought myself to ejaculation.

On some level, we hadn’t expected the first time to be amazing. Though it’s hard to make bad sex better, we had to try. We loved each other. We went on six more FRP visits, but the situation didn’t improve. Our issues were less about friction and more about fantasy, or the lack thereof.

Danielly had sent me letters over the years since we’d first met, none of which I’d replied to. But in 2015, as my relationship with Raina was coming to an end, I finally wrote back, explaining my marital woes. Danielly replied that I never should have gotten married in the first place, that she was my soulmate. She said she was still on and off with her boyfriend, but he didn’t matter. If I got divorced and married her instead, she’d come to Attica and fulfill all my fantasies.

I divorced Raina and proposed to Danielly.

In October, we got married by the same Attica town clerk who’d officiated the last time. The Goofy mural was gone. We posed for our wedding picture in front of a seascape of sea lions and colorful fish. Danielly looks sad in the photo, barely smiling. She’d wanted this day to be so much more special than it was.

Afterward, I bribed a CO with a few packs of Newports to let the cellblock’s tattoo artist come into my cell, and with a needle made from an uncoiled lighter spring powered by a repurposed beard-trimmer motor, he inked danielly on the inside of my upper arm in looping script. Once she ditched the boyfriend for good, she had my name inked on her forearm. We craved each other. Our kisses, deep and long and wet, always felt like good sex.

I wanted to transfer to Sing Sing, forty miles north of New York City—among other reasons, it would take Danielly an hour by train, as opposed to the eleven-hour bus trip she took both ways to visit me at Attica. But Attica was a disciplinary prison, rife with violence; the number of prisoners on good behavior was low, the FRP waitlist short. You could book a spot every forty or fifty days. At Sing Sing, the wait was closer to ninety days. I weighed the pros and cons. Con: waiting twice as long to be together. Pro: saving Danielly the hassle of a big trip to the middle of nowhere, which would probably mean I’d see her more often.

I submitted my paperwork, got approved, and transferred in November 2016.

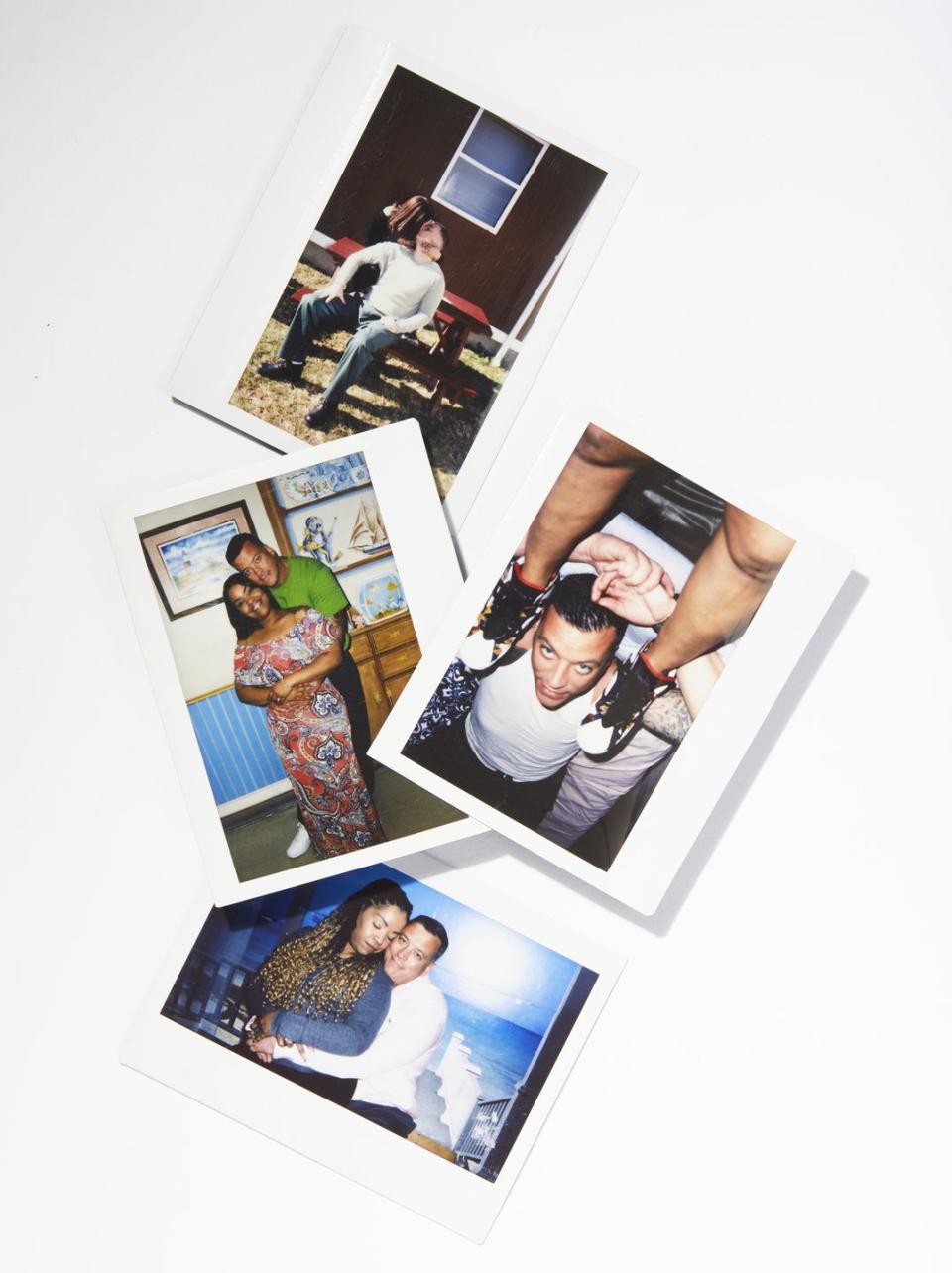

In February, we had our first FRP date. The compound was pretty much the same as the one at Attica, but at Sing Sing we got a Polaroid camera and twelve blank photos. Some couples went into the units and did not come out for the allotted forty-eight hours. Others were more social. Me and my friend Andy Gargiulo—convicted in 2006 of killing his reputed mobster brother-in-law; we’d had the same lawyer—would sometimes coordinate our FRP visits. He was a lot older than me, around eighty, but we got along. So did our better halves. His wife brought the best Italian food in Brooklyn—cannolis, fresh mozzarella, and tender veal—and when the weather was nice, the four of us would sit outside and barbecue.

Danielly was provocative, and that turned me on. We argued; we canceled visits on each other. We often had angry, shit-talking sex. Sometimes we played nice, but she’d never let it get to my head. “Boy,” she’d say, “you have so much to learn about women.” We couldn’t have sex for the entire forty-eight hours, but it sometimes felt like we were trying.

Intimacy came in other forms. She introduced me to ASMR; I brewed Bustelo for her and microwaved the half-and-half so it wouldn’t cool off the coffee too much. “Coffee,” by Miguel, became our song. We watched The Notebook, and she recited her favorite lines. We watched Warrior, and when Tom Hardy’s character hugs his drunk father, played by Nick Nolte, Danielly comforted me as I cried.

I know now that our relationship wasn’t healthy. My moments of joy were outweighed by my jealousy and anxiety. I’d get annoyed if she didn’t read my latest article. “You’re all into yourself and your career,” she’d say. “Women don’t like that, bro!” Or “I fell in love with the guy at Attica, before he became the writer.” That one hurt. But it’s not like I’d ask about her job as a nurse at a Bronx clinic. She’d want to talk about our future, and I’d urge her to stay in the present. She’d storm off into the bedroom, slam the door, and curse me out in rapid-fire Spanish. Well, I’d think, this is life.

By March 2020, our relationship was rocky. But for the first twenty-four hours of our first FRP in more than a year, we were getting along. As we prepped lunch, a knock came at the door. It was the security captain. Because of Covid, our visit was over, along with our last shot at rekindling.

By the time FRP visits were restored, a year and a half later, I’d been transferred to Sullivan Correctional, in the southern Catskills. Danielly came up twice. But too much time had passed, and other relationships had formed: hers with somebody else, mine with my career. Becoming a journalist in the joint brought its own stress, and my anxiety worsened; things like pissing in a cup with a guard peeking seemed impossible. Recently, we divorced.

Would I have been better off not having experienced intimacy for the past twenty-one years? Would Raina and Danielly have been better off never having met me? I’ve since realized that in both relationships, I focused more on the affection I was getting than the affection I was giving. All this time spent living in my head, confined to a six-foot-by-nine-foot cell, has rendered me less expressive and more emotionally stuck. My thoughts would bounce around my brain but never make it out of my mouth, which left Raina, then Danielly, feeling neglected. The time I used to spend writing love letters I now spend writing articles. Sometimes I feel like I took the two of them for granted. There’s an immense effort, this leap toward love in which the only physical manifestation comes in the form of conjugal visits. And it’s exerted not by the prisoners but by our partners. They wait, they shop, they lug, they travel, they get gossiped about by friends and family and insulted by COs.

Trailer visits were never perfect. Sometimes they were hard, especially at the end—me returning to prison, my woman going home alone. But in many ways, they felt like rehearsals for life on the outside. I believe that because of my experiences with conjugals, when I do get out, I’ll be more sensitive to the feelings of those closest to me. “It remains utterly and inescapably true that to be a human being is to need to be connected to, to bond with, and to be nurtured by other human beings,” Heather Ann Thompson told me. “Serving one’s sentence does not change that.”

So I’m single now. Middle-aged, too. Sometimes I imagine the kind of woman I’ll attract when I’m on the outside, and I wonder if I’ll resent her because she didn’t fall for me when I was on the inside. Which is absurd, and I know I need to work that shit out. But it also feels like a nod to the women who’ve loved me, a thank-you to all the partners who’ve sacrificed so much to share their love with those of us who are locked up.

I think about a moment Danielly and I shared with Andy and his wife, who was wearing Prada glasses and a perfume called La Vie Est Belle. The sun was bright; we sat at the picnic table, eating the best of both kitchens. Andy was talking about a TV show he watched in his cell—maybe it was America’s Got Talent—and Danielly told him how she also loved that show. While recalling the final performance of a child singer who’d recently won, Andy choked up. Right there at the wooden table, surrounded by the thirty-foot concrete wall and the guard with the AR-15 perched in the tower. Danielly teared up, too. “He gets emotional on these visits,” Andy’s wife said in a tough Brooklyn accent, smiling. More than the sex, it’s moments like these—simple, safe, and endearing—that have provided me with what prison has stripped away: a taste of intimacy.

You Might Also Like