Seventy years later, what is Brown v. Board's legacy in Milwaukee?

Seventy years since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation of students to be unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, Milwaukee metro-area schools are among the most segregated in the country.

More concerning to some: They are also unequal by many other measures, from funding to test scores.

In the years that followed the 1954 Brown v. Board decision, Milwaukee and state officials attempted a series of programs to desegregate schools in pursuit of equality, sending school buses crisscrossing communities otherwise constrained by housing discrimination.

Some of those bus routes are still running today. While some students count themselves lucky to have ridden those buses, many are still seeking a better solution to the basic problem that led to Brown v. Board: students of color being excluded from educational opportunities afforded to white students.

In advance of the May 17 anniversary of the court decision, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel spoke with three education leaders who experienced the impacts of the court ruling over the last 70 years — and whose own legacies will help shape the next 70.

'Having to get on a yellow bus to go to the south side to get a decent education didn’t fly with me'

Marva Herndon was a student at Milwaukee's Siefert School when the Brown v. Board decision came down. She doesn't remember it much; her neighborhood school was already integrated, she said.

Other Milwaukee schools were not as diverse. They drew students from their surrounding neighborhoods, which themselves had been deeply segregated by a long history of racist housing policies.

In 1962, civil rights attorney Lloyd Barbee moved to Milwaukee to confront the issue. Many Black students were overcrowded in substandard school buildings, he argued. The district's solution in some cases was to bus classrooms of Black students to majority-white schools — while keeping them separated at school. Ultimately, Barbee sued in federal court, and in 1976, Judge John Reynolds ordered MPS to actively desegregate its schools.

By that time, Herndon had her own children in Milwaukee. She was skeptical of the plan MPS put forth.

Some activists pushed for a two-way busing program through which some students from the north and south sides would swap schools, evenly distributing the burden of busing across populations. Instead, the district opted for a “voluntary” busing system, still in place today, involving citywide specialty schools meant to attract students from a cross-section of neighborhoods.

Community organizer Larry Harwell argued the plan effectively burdened Black students with busing across the city, as many of their neighborhood schools were shuttered or replaced with specialty schools. Far fewer white students were busing out of their neighborhoods. He also warned that as Black students were bused into majority-white schools, their needs would take a back seat to those of white students, they would experience discrimination and the district would lose Black teachers.

As the busing programs rolled out, Herndon kept her children at their neighborhood school.

"Having to get on a yellow bus to go to the south side to get a decent education didn’t fly with me," Herndon said. "My thing, much as it is today, was there should be equity throughout the district."

When it was time for her children to go to high school, she supported their choices to pursue specialty high schools. That brought its own frustration.

One of Herndon's daughters wanted to go to Washington High School to pursue her interest in accounting but, Herndon said, she "couldn't get in because her race did not enhance the racial balance of Washington." In 11th grade, Herndon said, her daughter was allowed to go to Washington part time without being counted as a student at the school. She was finally fully allowed at the school her senior year.

Herndon's other daughters were able to attend Riverside High School and Milwaukee High School of the Arts to pursue their own interests. One was interested in engineering and now works at NASA. The other pursued music and now works in early education.

Herndon is proud of the district's specialty schools, and she also wants to ensure students never have to leave their neighborhood to get a high-quality education. She feels the emphasis on busing broke up the fabric of communities.

"That sense of community is gone by losing the neighborhood schools," Herndon said. "We grew up walking to and from school. You knew the kids down the block, your parents knew each other, you went to church together. All of this kind of thing is gone. I think it’s really damaged society because of that."

Now the president of the Milwaukee School Board, at a time when test score gaps between Black and white students have been growing and are among the worst in the nation, Herndon said she thinks the answer is in the funding formula for schools.

At the top of her list: full funding for special education services. Wisconsin reimburses schools for only about a third of the cost, leaving districts to pull from their general aid to cover the rest. The shortfalls are tend to be highest for districts with higher rates of poverty as those districts have higher numbers of students who need the services.

Herndon also advocated for two referendums to raise funding for MPS to support and maintain arts and music programs, a feat that was celebrated recently with a citywide music festival. "I felt like a proud grandma," Herndon said.

'The school seemed like two different schools'

In fall 1984, sophomore Mary Pattillo, who lived near Milwaukee's Rufus King High School, boarded a bus to start at a new school in Whitefish Bay. She had just joined the Chapter 220 program.

The program, launched by state lawmakers in 1976, was an attempt to chase the segregation problem as white families left the city for the suburbs. It funded the transfer of students between city and suburban schools.

Pattillo had gone to the private University School of Milwaukee for her freshman year, which she described as "too much of a culture shock." She wanted to transfer to King, five blocks from her home, which MPS had turned into a magnet program. But Pattillo wasn't able to get in. She had a cousin in the 220 program at Whitefish Bay and decided to try that.

Pattillo described the 220 experience as "desegregation without integration." Students in the program tended to stick together, and they generally had to leave on buses at the end of the school day while Whitefish Bay resident students participated in extracurriculars.

"The school seemed like two different schools," Pattillo said.

Students were also tracked based on academic performance, or perceived academic performance. When Pattillo was put on an honors track, she was often the only Black student in her classes.

Still, Pattillo credits her 220 experience with where she is today: chair of Northwestern University's Black Studies Department, where she has researched education and inequality, among other subjects.

For one, she said Whitefish Bay was a well-funded school: "The main mechanism of that positive impact is resources. Desegregated school districts end up spending more money per pupil, and Black kids benefit from that," she said, referencing research by Rucker Johnson.

The program also exposed her to the inequity that she bridged each day on her bus route.

"I was really impacted by the commute every day from my working class Black neighborhood to Whitefish Bay, and the differences in resources, and the stark division. There were no Black kids who lived in Whitefish Bay in my class, that's how white it was," she said. "That experience of traversing the city to the suburbs and experiencing that level of segregation is what made me interested in metropolitan areas, in inequality, and what I've now studied my whole life."

The same year Pattillo started the program, MPS took the suburbs to court, asking a judge to force the suburbs into an integration plan. Under a settlement agreement, the parties agreed to expand the 220 program to 23 suburbs.

That program is now being phased out. It stopped accepting new students in 2015, and the last of the remaining students are on track to graduate in 2029. Asked what she thought about the program's end, Pattillo said it should be paired with improvements to city schools.

"I would look to see if ending this program does coincide with new investments in the options that parents who live in Milwaukee will now have to choose between," Pattillo said. "What I definitely think is not a good thing is to close 220 and not do the kind of investment in Milwaukee schools so that parents have good options in Milwaukee."

Pattillo added, looking at projections of white people becoming a minority population, that desegregation may be a less and less effective vehicle for ensuring equal educational opportunities. Rather, she emphasized securing more funding for under-resourced schools.

"Desegregation can't be the basket where we put all of our eggs because it prioritizes sitting next to white students, and white students are becoming fewer and farther between in these school districts," she said. "We can't think that just putting kids next to white kids is going to be our solution."

'There’s the world that I wish existed, and then there’s the world that exists'

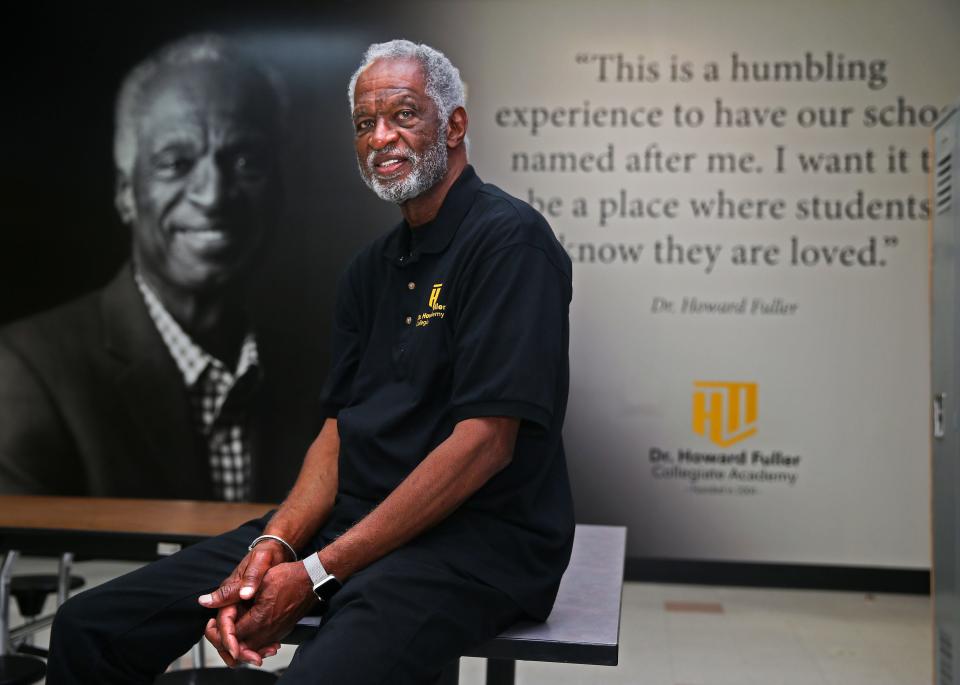

In 1964, Howard Fuller faced off with a bulldozer while trying to block construction of a segregated school in Cleveland. Another protester was killed by the bulldozer that day.

At the time, Fuller said he considered himself an integrationist. In subsequent years, while he applauded the Brown v. Board decision for outlawing segregation, Fuller came to oppose many of the measures taken to enforce integration, including at his own alma mater, Milwaukee's North Division High School.

"You can’t say Brown was of no value because it was significant in the fight against legal apartheid," Fuller said. "But it was not an educational strategy that has proven to be universally beneficial for Black people."

Fuller said he was heavily influenced by Malcom X's "The Ballot or the Bullet" speech, which he heard the same month that he faced the bulldozer. Advocating for Black nationalism, the speech urged listeners not to try to "change the white man's mind" but to build power in Black communities to control their own institutions.

Fuller also heeded comments made by Martin Luther King, Jr., cautioning against being "integrated out of power," rather than "into power." Fuller said he watched Black communities lose power under school desegregation orders.

"Black educational institutions were closed, Black teachers lost their jobs, and Black educators' opinions were devalued, in the way that 'desegregation' was implemented," Fuller said. "So the fear that Martin Luther King and other Black educators had back then was exactly what happened: Integration was done in a way that cost Black people dearly."

MPS's own planning documents show how it prioritized the protection of white students, Fuller said, providing a 1976 draft plan that noted MPS "must not promote or encourage so-called 'flight'" from the district.

"The psychological guarantee of not having to attend a school that is predominantly minority will tend to stabilize the population in the city," the plan stated.

In 1979, following the desegregation order from Reynolds, there was a proposal to make a magnet school at North Division, which would mean many of the neighborhood students would be bused somewhere else. Long before he became superintendent for MPS, Fuller successfully advocated for the school to be allowed to remain predominantly Black.

Fuller has spent much of his career advancing plans for predominantly Black schools in and outside of MPS, with more success outside. Fuller supported a failed plan to create a separate, predominantly Black school system in Milwaukee. When he served as superintendent of MPS from 1991 to 1995, his major plan to expand school facilities, thus averting overcrowding and busing, was voted down.

Fuller increasingly championed voucher and charter school movements, growing pessimistic about MPS. He supported the 1990 creation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, which provided tax-funded vouchers for low-income families to enroll in private schools.

"There's the world that I wish existed, and then there's the world that exists," Fuller said. "And in the world that exists, I don't see how poor people are going to be advantaged unless they have a way to impact the flow and distribution of money."

In 2004, Fuller co-founded a charter school in his name, where 97% of students are Black.

Asked whether he thinks voucher and charter schools have improved outcomes for Milwaukee students, he said: "For some kids. That's why I say this has been a rescue mission, not a systemic change, because unfortunately there are private schools that are not any good, there are charter schools that are not any good, there are MPS schools that aren't any good. On one hand, the change that I hoped for has occurred. On the other hand, the change that I hoped for has not occurred."

Fuller said he has seen his own school help students go on to college who he believes otherwise would not have done so. But as he prepared recently for the senior banquet, he remained skeptical about the bigger picture.

"I go to this banquet, and I’m worried about the same thing that I worry about every year that I’ve been to the banquet," he said. "I worry about what’s going to happen to each one of these kids. No matter how hard we try, not all of these kids are going to be adequately prepared for the world that they’re going to confront. It's still a society where your race is going to impact what's happening."

Contact Rory Linnane at rory.linnane@jrn.com. Follow her on X (Twitter) at @RoryLinnane.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Seventy years later, what is Brown v. Board's legacy in Milwaukee?