Seniors vs. the poor? Democrats stare down stark tradeoffs in trying to fund health care expansion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WASHINGTON – Democrats wrestling over how to downsize their multi-trillion dollar domestic agenda to accommodate the lower spending levels demanded by moderate senators are facing tough political choices on competing health care plans.

If they don’t extend recently expanded health insurance subsidies, premiums will rise for millions of Americans right before the 2022 midterm elections.

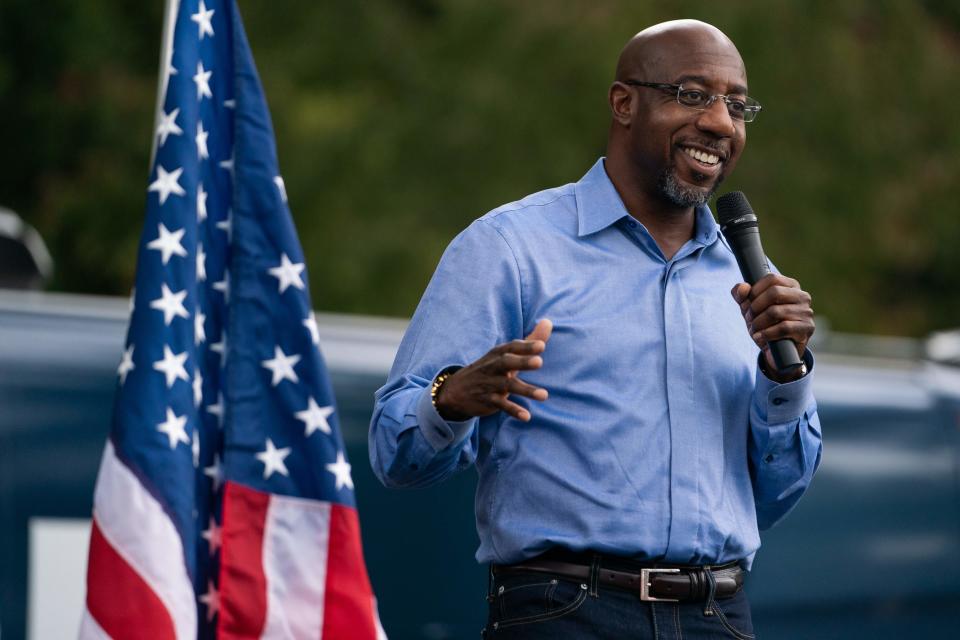

If Democrats don’t offer Medicaid coverage to the millions of poor Americans left out of the program in a dozen states, Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock, for example, won’t be able to deliver on a top priority before he faces re-election next year in the swing state that gave Democrats the Senate majority.

If they do expand Medicare to include dental, hearing and vision benefits, seniors – who are more likely to cast ballots than younger voters – could be motivated to pull the lever for Democrats.

If Democrats spend billions on home health care for disabled and older Americans, the wages of care workers will rise – a priority for labor unions that endorsed President Joe Biden and can help turn out voters.

“Each of these provisions appeals to a particular political constituency,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. “So it’s going to be hard for Democrats to pick and choose among these health care programs.”

Powerful champions

Each option also has powerful champions.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., wants Obamacare’s premium subsidies permanently boosted to bolster the coverage expansion started by the Affordable Care Act, her biggest legislative accomplishment to date.

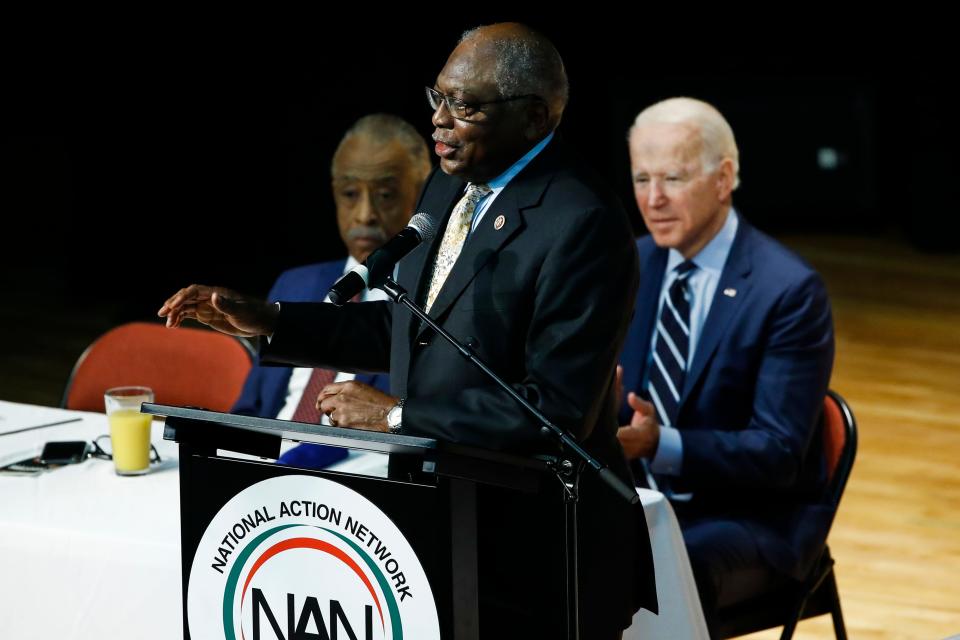

Besides Warnock, expanding Medicaid in the states that have rejected the ACA is a priority for House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn, D-S.C. In addition to being the No. 3 Democrat in the House, Clyburn’s endorsement of Biden’s presidential bid ahead of the South Carolina primary played a critical role in Biden’s winning the nomination.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, as well as other progressives who are insistent that the party not cave to more moderate lawmakers, has said expanding Medicare benefits is a must-have item.

Biden, who has made advancing equity a top issue for his administration, has emphasized that the caregivers whose pay would improve by spending $400 billion more on home and community-based services are largely women of color.

Best bang for the buck?

Trying to prioritize the expensive plans by which would deliver the biggest health benefit is also difficult.

Many advocates and health care experts say it’s clear that getting health coverage to those who don’t have it now should be the top priority, which means expanding Medicaid.

“Expanding dental benefits and Medicare may very well be worth doing,” said Matthew Fiedler, a former member of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers who is now at the Brookings Institution. “But if you're in a world of constrained choices, I find it hard to argue that it’s as valuable on a dollar-for-dollar basis as providing health insurance to a poor person who doesn't have that.”

But John Holahan, an expert at the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center, said there’s no simple answer to which proposal would deliver the most health care for the cost.

“All these four have different target populations and would do some good for those populations,” he said. “So, the bang for the buck really depends on which populations you care most about.”

Democrats could take the hugely popular step of controlling prescription drug prices, which would not only benefit consumers but also give the federal government more money to spend on other health priorities.

But that would require overcoming fierce opposition from the powerful pharmaceutical industry – which argues lower prices would hurt the development of new drugs -- and from some fellow Democrats who side with the industry.

“People have been trying to do this for almost two decades. The American people are fed up,” said Frederick Isasi, executive director of the advocacy group Families USA. Isasi said he is optimistic, based on what he’s hearing as the legislative details are being worked out, that the final version will address drug prices. But he predicted it will be an “edge of our seat fight until the end.”

Who is Joe Manchin: The West Virginia senator says he wants to make Congress ‘work again’

Democrats’ dilemma is caused not just by the fact that they have few votes to spare in the House and none in the Senate where two Democrats – Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona – have balked at the $3.5 trillion price tag on the sweeping social safety net bill to improve health care and much more.

They’re also constrained by the fact that, even as health care remains a top priority for the party, Democrats are still trying to fix problems with the more than decade-old Affordable Care Act while many in the party want to move beyond Obamacare towards a new overhaul of the system.

Unfinished business

Twenty-one former House Democrats who lost re-election after casting what they knew would be a politically risky vote for the ACA have urged party leaders to finish the work for which they sacrificed their seats.

“We voted for that law knowing it was imperfect and would need improvement and strengthening in the years to follow,” they wrote last month.

Democrats' efforts to hold down the overall cost of the ACA kept them from making the subsides as large as they wanted in 2010, leaving some lower- and middle-income earners to struggle to pay premiums and deductibles.

Congress temporarily fixed that in the $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package passed in March that included a two-year expansion of premium subsidies for people who purchase insurance on their own instead of getting it through an employer or the government.

Subsidies became more generous for those who already qualified for assistance, lowering both premiums and deductibles. They were made newly available to people earning more than four times the federal poverty rate – about $51,000 for a single person.

Unless those changes are extended, premiums would double on average for millions of enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Those lower- and middle-class consumers would begin discovering they would be paying an average of $800 per year more shortly before voters next decide who will control Congress.

“If the ACA premium help is not extended,” Levitt said, “marketplace enrollees will get a nasty surprise right before the midterm election.”

Health care for the poor

The ACA was also supposed to expand Medicaid to people earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level. But the Supreme Court ruled that states didn’t have to go along, even though the federal government pays most of the cost of those newly eligible for the jointly financed program.

Democrats included in the March pandemic relief package billions of dollars in new incentives for the dozen states that have resisted. None have bit.

A disproportionate share of the millions of uninsured in those states who could gain coverage if Congress created a workaround are people of color, making it a racial justice issue for many Democrats, including Clyburn.

Those who would benefit are also mostly in GOP-led states in the South, where Democrats have struggled to make political gains.

But one of those states is Georgia which, Warnock likes to remind his colleagues, delivered the final Senate seats Democrats needed to take control of that chamber in January.

“In states like Georgia, where voters cast their ballots in historic numbers to reshape the makeup of our federal government, it is incumbent on Congress to honor that commitment by expanding access to Medicaid coverage in non-expansion states,” Warnock wrote in recent opinion piece for USA TODAY.

Sen. Warnock: Congress should fund health care coverage for poor in states that won't expand Medicaid

The poor, who would be helped by the expansion, do not have lobbying clout in Washington or political heft at the polls. They do, however, have the support of a number of nonprofit and philanthropic organizations who argue it’s long past time to achieve universal health care coverage in the United States.

“And the most important step we can take right now toward that goal is to close the Medicaid coverage gap once and for all,” more than a dozen groups said in a joint statement signed by the Robert Wood Johnson foundation, the American Heart Association, the March of Dimes, the NAACP and others.

Expanding Medicare

Sanders and other progressives have long argued the best way to provide health care for all Americans is through one government-run program, shorthanded as Medicare for All.

That is not on the table, nor is lowering the enrollment age for Medicare.

So the next best thing is adding more Medicare benefits.

“We want to expand Medicare so elderly people can chew their food, can have hearing aids, can have eyeglasses,” Sanders said recently.

The Washington Post has reported that including the benefits was a prerequisite for Sanders before he agreed to back a reduction in cost for the entire package.

But it’s gotten pushback.

“It hardly seems 'progressive’ to provide more generous coverage for Medicare beneficiaries when millions of Americans have no health coverage at all,” the centrist Progressive Policy Institute wrote in a recent report outlining what it would prioritize in a scaled-back plan.

An estimated 7 million people would gain health insurance by filling the Medicaid coverage gap and making permanent the expanded premium subsidies, according to researchers at the Urban Institute.

Possible solutions

Short of leaving out any of the proposals entirely, Democrats could include less expensive versions.

Biden has laid the groundwork for that approach to various elements of the package, saying this month that major fundamental shifts are seldom caused by just one legislative action. Social Security, he noted, looks nothing like the much smaller program it was when created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“We don’t have to get everything all at once,” Biden said during a trip to Michigan Tuesday to push for the pending package.

An easy way to do that is to sunset the programs so their cost in the budget scoring window is lower, in hopes that they will become too popular to end.

Fiscal watchdogs like Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, warn against such “timing gimmicks.”

“We’ve seen this game before,” she said. “When they expire, there will be immense pressure to authorize them and extreme reluctance to pay for them.”

That would not only be bad for the nation’s fiscal health, she argues, but also “highly disruptive to the very people the programs are supposed to be helping.”

Sarah Lueck, vice president for health policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said that’s particularly important for the millions of poor people who have been waiting for years to be eligible for Medicaid in the hold-out states.

“You need to give people time to actually enroll and benefit from the fact that they have coverage,” she said, “and then you need to not take it away after they've waited so long to get it.”

Fiedler, the health policy expert at the Brookings Institution, has laid out ways to reduce the cost of the proposed new Medicare benefits.

Seniors could be asked to cover 25% of the cost, similar to premiums charged for Medicare’s physician and drug benefits.

Lawmakers could also lower the payments private insurers get for providing Medicare plans. Insurers might earn lower profits and offer fewer other supplemental benefits but seniors would still have more help overall, Fiedler said.

The Kaiser Family Foundation’s Levitt said Democrats are likely to find a way to include some form of all the proposals in any final package.

“They’ve created expectations for these expansions, and each of them have advocates in Congress that would be hard not to accommodate,” he said. “There are political payoffs and landmines everywhere in this debate.”

A closer look: Can the true cost of Biden's budget plan really be 'nothing'?

'Close the deal': Biden struggles to unite Democrats behind his economic agenda

Maureen Groppe has covered Washington for nearly three decades and is now a White House correspondent for USA TODAY. Follow her on Twitter @mgroppe.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Democrats face tough choices in trying to fund health care goals