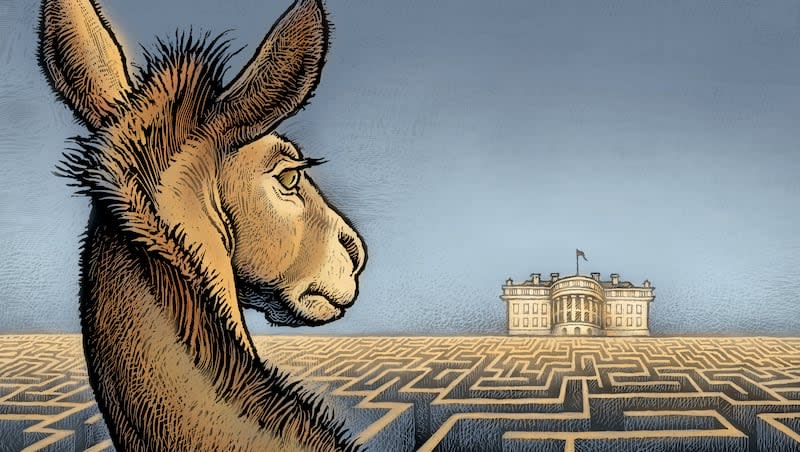

Sell outs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

We toured Dundalk, a once-prosperous blue-collar town east of Baltimore, where many of its inhabitants worked at the huge Bethlehem Steel plant at Sparrows Point that at its peak employed 30,920 workers or at the General Motors plant in White Marsh that had employed 7,000. Dundalk, which is almost entirely white, was dependably Democratic in presidential and congressional elections until 2004, when its residents narrowly backed George W. Bush against John Kerry. Its local administration was solidly Democratic, but in 2014 it became Republican. In the 2016 election, it backed Donald Trump by 62 percent to 33 percent over Hillary Clinton. In 2020, Trump won Dundalk by 57 percent to 40 percent.

We interviewed Robert Price, who is in his 50s and worked at the GM and Bethlehem plants and now works at a shipyard. Price says he took “the last train of industrialism out of the station.” Price, who in 2004 went to Iowa to campaign for labor Democrat Dick Gephardt, now supports Trump. As we are driving to Dundalk, we asked him why so many white workers have left the Democratic Party and turned to Trump and the Republicans. “I mean a lot of it is AM radio,” he says. “There is a racist element to it. There is no question of that.” But he rejects that as too simple an explanation. “To me there are only two groups of people, the globalists and the nationalists, and unfortunately the Democrats have wound up appearing to be the friends of the globalists. And the nationalists, the Black people at work, they are veterans, they side with the right, the Republicans. In other words, it’s more about class than color, it’s more about nationalism than race.”

We turn into Dundalk, and he continues, “I think the blue-collar working-class people are the more nationalistic people. I think the Democrats are what we used to call the jet-setter class. They are the ones who go to Europe on vacation. They are the ones who don’t care where the stuff is made. I think the working class has caught on to that.”

There are now hundreds or even thousands of small towns and midsize cities across America where working-class Americans express opinions about the Democrats that resemble what Robert Price described. While Dundalk is predominately white, you can now find similar sentiments in small towns where many of the inhabitants are Hispanics or Asians or among some working-class Black people. Of course, they know that not all the people who are Democrats are jet-setters or globalists, but that’s how they now see the leaders of the Democratic Party and their political outlook. These working-class voters used to be the lifeblood of the Democratic Party. Now they are abandoning the party. That’s not good news for the future of the American experiment.

“I think the blue-collar working-class people are the more nationalistic people. I think the Democrats are what we used to call the jet-setter class. They are the ones who go to Europe on vacation. They are the ones who don’t care where the stuff is made. I think the working class has caught on to that.”

The Democratic Party has had its greatest success when it sought to represent the common man and woman against the rich and powerful, the people against the elite and the plebians against the patricians. During the height of Jacksonian democracy, which endured two decades, Democrats spoke for the newly emigrated, the working man and the small farmer against the merchant and banking class of northeastern Protestants. During Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, Democrats represented the “forgotten American” and “the people” against the “economic royalists” of Wall Street and corporate boardrooms. As Frances Perkins, Roosevelt’s secretary of labor, put it, “The ‘new deal’ meant that the forgotten man, the little man, the man nobody knew much about, was going to be dealt better cards to play with.”

Both the Jacksonian and the New Deal Democrats had their failings — and they were egregious in Jackson’s case. Jackson waged a brutal war against Native Americans and was a slave owner, but Jackson and Martin Van Buren, his political guru and successor, presided over the expansion of American suffrage and the birth of the modern American party system and defended the Union against the first threat of Southern secession. Roosevelt compromised with Southern segregationists to win needed support to pass Social Security and other pathbreaking measures. These measures vastly expanded the federal government’s responsibility for the welfare of its citizens, including the old and disabled. Roosevelt also signed legislation that enabled workers to vote for unions, laying the basis for the modern labor movement and for modern American pluralism, where labor could provide a countervailing force to the power of business. These reforms narrowed the gap between the people and the powerful. They contributed to decades of prosperity and to growing equality. They were as close as America has come to a social democratic politics and polity.

Over the last 30 years, the Democrats have continued to claim to represent the average citizen. In his 1992 campaign, Bill Clinton championed “the forgotten middle class” and promised to put “people before profit.” Barack Obama pledged that the “voices of ordinary citizens” would “speak louder” than “multimillion-dollar donations.” Hillary Clinton in her 2016 campaign promised to “make the economy work for everyday Americans.” And Joe Biden was running in 2020 to represent “the people.”

“They’re the reason why I’m running. These are people that build our bridges, repair our roads, keep our water safe, who teach our kids, look, who race into burning buildings to protect other people, who grow our food, build our cars, pick up our garbage, our streets, veterans, dreamers, single moms.”

Biden’s appeal was clearly genuine, but over the last decades, Democrats have steadily lost the allegiance of “everyday Americans” — the working- and middle-class voters who were at the core of the older New Deal coalition. Initially, most of these voters were white, but in the last elections, Democrats have also begun to lose support among Latino and Asian working-class voters as well.

How did this happen? There is an original reason, for which the Democrats were hardly to blame. Democrats were the principal supporters of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — measures that went a long way toward ending racial segregation and Jim Crow, but that angered many Southern white people and, to a lesser extent, some white people in the North. “Well, I think we may have lost the South for your lifetime — and mine,” Lyndon Johnson told his aide Bill Moyers after he signed the 1964 bill. According to Moyers, it was said “lightly” and was a “throwaway thought,” but it proved at least partly true. With the exception of a few far-right groups, however, Americans have reconciled themselves to those bills. Democrats regularly win elections in Virginia, the seat of the Southern Confederacy, and many of the northern and southern suburbs formed by white flight now vote for Democratic candidates. And Americans elected an African American president in 2008 and reelected him in 2012.

There is no single factor that has driven working-class voters out of the Democratic Party.

They include:

Democrats’ support for trade deals that led to factory closings in many small towns and midsize cities in states that were once Democratic strongholds.

Democrats’ support of spending bills that the working and middle classes paid for but that were primarily of benefit to poor Americans, many of whom were minorities.

Democrats’ support of immigration of unskilled workers and the party’s opposition to measures that might reduce illegal immigration.

Democrats’ support for abortion rights (and opposition to any restrictions on these rights).

Democrats’ support for strict gun control.

Democrats’ support for and identification with the quest for new identities and lifestyles, particularly among the young, and denigration of all those who were not supportive.

Democrats’ insistence on eliminating fossil fuels.

Democrats’ opposition to open displays of religiosity.

Democrats’ support for the desecration of national symbols, such as the flag or national anthem, to dramatize discontent with injustices.

Democrats’ use of the courts and regulations to enforce their moral and cultural agenda, whether on the sale of wedding cakes or the use of public men’s and women’s bathrooms.

Not all Democrats are in line with these actions or beliefs. But overall, they came to characterize the party. Some of these stances have to do directly with economics; others with culture. The differences over them are often taken to distinguish the college-educated professional from those who do not have college degrees, but they equally, if not more accurately, arise from the differences in economic geography — what we call the “Great Divide” in American politics.

On one side of the divide are the great postindustrial metro centers like the Bay Area, Atlanta, Austin, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, New York and Seattle. These are areas that benefited from the boom in computer technology and high finance — the areas economist Robert Temin dubs “FTE,” for finance, technology and electronics. These areas are heavily populated by college-educated professionals, but also by low-skilled immigrants who clean the buildings, mow the lawns and take care of the children and the aged. The professionals, who set the political agenda for these areas, welcome immigrants who entered the country legally and illegally; they want guns off the street; they see trade not as a threat to jobs but as a source of less expensive goods; they worry that climate change will destroy the planet; and, among the young, they are engaged in an anxious quest for new identities and sexual lifestyles. A majority of them are Democrats.

If you want an extreme counterpart to Dundalk, it is Mountain View, a posh town (population 80,000) that is part of Silicon Valley. Alphabet (Google) and Meta (Facebook) are both headquartered there. Its main drag boasts chic boutiques and restaurants. Starter houses go for nearly $2 million, and rents run $3,000 a month for a one-bedroom. Many incomes are in the six-, seven- or more figure range. The area once leaned Republican. In 1980, Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter by 13 points in Santa Clara County. It is now overwhelmingly Democratic. Biden won 83 percent of the vote in 2020. Its congressman is Ro Khanna, who was national co-chair of Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign.

But its Democratic politics diverge from the older New Deal liberalism. His constituents, Khanna explained to us in an interview in his Capitol Hill office, are drawn to the Democrats primarily by social issues. They are “vehemently pro-choice, vehemently pro-gay marriage, vehemently for reasonable gun safety legislation. Yeah, vehemently pro-immigration in terms of recognizing that immigrants improve the nation and care deeply about climate.” Former Mountain View Mayor Lenny Siegel said about the politics of Mountain View’s residents, “They are progressive on national issues, but they don’t want to see dense housing built near them.” Mountain View has a minimum wage of $18.15, but in 2020 its residents backed an initiative restricting parking by recreational vehicles (the only viable housing for many of the lower-wage service workers) in their small city.

The cost of housing is a big issue for young tech workers, but they are indifferent to labor unions. “The thing about tech people,” Siegel told us, “is that they can easily find another job if they are unhappy. If they stay at the same job for too long, it looks bad on their résumé. There is a lot of occupational mobility. People who are unhappy can solve the problem themselves.” That could change, of course, with the wave of layoffs that began in early 2023, but Siegel expects the downturn to be temporary.

Democrats’ unwillingness to acknowledge the mote in their own eyes has hurt the party’s chances to win back working-class voters.

On the other side of the divide are the small towns and midsize cities that have depended on manufacturing, mining and farming. Some of these places have prospered from newly discovered oil and gas deposits, but many are towns and cities like Muncie, Indiana; Mansfield, Ohio; and Dundalk that have lost jobs when firms moved abroad or closed up shop in the face of foreign competition. The workers and small-business people in these towns and cities want the border closed to immigrants who enter the country illegally, whom they see as a burden to their taxes and a threat to their jobs; they want to keep their guns as a way to protect their homes and family; they fly the American flag in front of their house; they go to or went to church; they oppose abortion; some may be leery of gay marriage, although that is changing; many of them or members of their family served in the military; they have no idea what most of the initials in LGBTQIA+ stand for. A majority of them are now Republicans and many are former working-class Democrats.

The underlying divisions are economic, but the political battles between the parties now manifest themselves as a continuation of the culture wars that began in the late 1960s. In the 2021 and 2022 elections, for instance, Democrats and Republicans fought over abortion rights, crime and the police, voter fraud and suppression, critical race theory, sexual education and border security. These differences between the parties and their candidates have been reinforced and hardened by what we call the “shadow parties.” These are the activist groups, think tanks, foundations, publications and websites, and big donors and prestigious intellectuals who are not part of official party organizations, but who influence and are identified with one or the other of the parties.

The labor movement used to play a dominant role in the Democrats’ shadow party and kept it rooted in working-class concerns, but it had to take second or third place during the Clinton and Obama years to Hollywood, Silicon Valley and Wall Street, together with various environmental, civil rights and feminist groups. Currently, the shadow party includes organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union, the Sunrise Movement, Planned Parenthood and Black Lives Matter, publications such as The New York Times, MSNBC and Vox, foundations like Ford and Open Society, and think tanks like the Center for American Progress.

These shadow institutions have articulated the outlook of many young professionals in the large postindustrial metro centers and in college towns. On many of the cultural issues concerning race, gender and immigration that divide our politics, they have taken the most radical positions. Their counterparts on the right include the Koch Network, Heritage Foundation, the Center for Renewing America, Turning Point USA, Fox News, Breitbart.com and the Claremont Institute. These groups on the left and right subsist within their own closed universes of discourse, each shadow party using the extremes of the other to deflect criticism of their own radicalism.

With the parties at roughly equal strength — the Democrats’ losses in small-town America have been made up by their gains in the metro centers, and particularly in the suburbs — the parties have rarely enjoyed undivided rule. In the last 44 years, one party has held the White House and both houses of Congress in only 14 of them. The civics books will say that this rough equality encourages constructive compromise, but in the last three decades, it has more often been a recipe for gridlock and stalemate, epitomized in battles over increasing the debt limit and in repeated government shutdowns. This stalemate has increased voters’ distrust of Washington and of government.

In recent years, elections have increasingly been decided by which party can make the other party’s radical extremes or the politicians who represent those extremes the main issue. In 2016, Donald Trump succeeded in making the election about “Crooked Hillary.” In 2018 and 2020, the Democrats were able to make the election about Trump’s excesses. In 2022, Democrats won elections where the issue was Republican opposition to abortion rights and insistence that the 2020 election was stolen, whereas Republicans won when the issue was Democrats’ wanting to defund the police or decriminalize illegal immigration.

The Democratic Party has had its greatest success when it sought to represent the commAon man and woman against the rich and powerful, the people against the elite, and the plebeians against the patricians.

There is a danger to democracy lurking in this transformation of the parties into cultural warriors. American democracy was originally based on the Jeffersonian idea that roughly equal property ownership (by white males) would undergird political equality and democracy. That notion was dashed on the rocks of the industrial revolution, which created a society of distinct economic classes. It was then hoped by liberals and progressives in the early 20th century that the intrinsic economic and political power of the lords of industry and finance would be counterbalanced by the power of labor unions in the workplace and by a party that represents the working and middle classes in the political realm. And that was the democratic pluralism that, with some obvious flaws, New Deal liberalism bequeathed and that dominated American politics from the 1930s up through the 1960s.

But that hope for democracy has also been shattered. During the last half-century, the labor movement, under assault from business and Republicans, has precipitously declined, particularly in the critical private sector. And the Democratic Party has ceased to be seen and to function as the party of the people in competition with the party of business. The consequences have been profound. Business and finance, through a plethora of lobbies that began springing up in the 1970s, have gotten their way time and again. The tax code has been dramatically rewritten to favor the wealthy and corporations, including those with subsidiaries overseas, at the expense of working America; trade deals have been signed that have aided multinational corporations, investment banks and insurance companies but hurt American workers; finance, with its propensity to instability, and its emphasis on short-term returns, has been enhanced at the expense of manufacturing; at the behest of the most retrograde elements, social programs have been sabotaged or rejected that would have provided American workers with the same security in health care, child care and employment that European workers simply take for granted; and conservative court decisions have gutted post-Watergate measures designed to limit the inordinate influence of corporations and the wealthy on political campaigns.

In our view, one prerequisite for reviving the promise of American democracy is the reemergence of a political party whose primary commitment is to look after the country’s working and middle classes. It could be the Republicans who end up being this party. There are new intellectual currents within the Republicans’ shadow party that are skeptical about the reign of big business and free market ideology and endorse a version of industrial policy. These include the think tank American Compass and the journal American Affairs. We wish them well. But we worry that they will be ignored because of the Republicans’ traditional commitment to business and the strength of business groups and donors within the Republicans’ shadow party. That was evident in the new House Republican majority’s first act in January 2023, which was to slash funds for the Internal Revenue Service that had been targeted for uncovering tax dodging by the wealthy. The Republicans, too, have a radical side whose propensities for violence and contempt for democracy outweigh the foibles of the Democrats’ cultural radicals.

We place our hopes for change in the Democratic Party. We see evidence in the Biden administration’s first two years of a reevaluation of the party’s economic priorities on trade, taxes and labor, and on national economic growth that tries to bridge the Great Divide. The Democrats seem to have turned a corner from their deference to free markets and free trade during past administrations. The influence of Wall Street and Silicon Valley remains a problem with the Democrats, but the main problem we see with today’s Democratic Party is the cultural insularity and arrogance that surfaced clearly during Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

Most of the stands the party and its groups take on issues like race, crime, immigration, climate, sex and gender have a rational basis and justification. There has been police brutality; the country’s 11 million immigrants who have entered the country illegally constitute an exploitable underclass that needs to be integrated into society; transgender people have suffered discrimination; and climate change is a genuine threat to the planet’s future. There are reasonable reforms that address these, but the radical solutions and the censorious outlook advanced by the Democrats’ shadow groups and by some Democratic politicians have been wrongheaded and divisive.

Many Democrats simply refuse to recognize this. Instead, they have succumbed to what we call the “Fox News Fallacy” — namely, that if Fox or the Washington Free Beacon or some Republican operative denounces Democrats for their stance on criminal justice or illegal immigration or gender affirmation, there can be no basis for those charges. Prior to the 2022 election, for instance, as Republicans were blaming Democratic support for defunding the police for a rising crime wave in big cities, Democratic pundits and politicians derided the very idea of a widely documented crime wave. The Washington Post’s Philip Bump wrote a column aptly entitled, “Crime Is Surging (in Fox News coverage).” Democrats’ unwillingness to acknowledge the mote in their own eyes has hurt the party’s chances to win back working-class voters.

The America of today is vastly different from the America of the 1930s, but what the Democrats need today is a general approach to politics that is similar to that of the New Deal liberals. The New Deal liberals were liberal, progressive and social democratic in their economic views, dedicated to creating a better balance of power between labor and business and security against poverty, unemployment, disease and old age, but by today’s standards, the New Deal Democrats were moderate and even small-c conservative in their social outlook. They extolled “the American way of life” (a term popularized in the 1930s); they used patriotic symbols like the “Blue Eagle” to promote their programs. In 1940, Roosevelt’s official campaign song was Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” Under Roosevelt, Thanksgiving, Veterans Day and Columbus Day were made into federal holidays. Roosevelt turned the annual Christmas tree lighting into a national event. Roosevelt’s politics were those of “the people” (a term summed up in Carl Sandburg’s 1936 poem “The People, Yes”) and of the “forgotten American.”

There wasn’t a hint of multiculturalism or tribalism. The Democrats need to follow this example. They need to press economic reforms that benefit the working and middle classes, but they need to declare a truce and find a middle ground in today’s culture war between Democrats and Republicans so that they can once again become the party of the people.

John B. Judis is editor-at-large at Talking Points Memo. Ruy Teixeira is a political demographer at the American Enterprise Institute.

Excerpted from “Where Have All The Democrats Gone?: The Soul of the Party in the Age of Extremes,” by John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira. Published by Henry Holt and Company. Copyright © 2023 by John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira. All rights reserved.

This story appears in the March 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.