From segregated NC to ACC elder statesman, FSU’s Leonard Hamilton forged his own path

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Of all the indignities Leonard Hamilton experienced growing up in segregated Gastonia — and there are too many to list and too many to remember — the one that perhaps stays with him the most is the one that brought him to tears late last month in his office at Florida State. More than 60 years had gone by, and Hamilton could still see what his mother never wanted him to see.

She wanted to protect him that way. Hamilton, ever curious, wanted to know.

And so he boarded a bus toward downtown. His mom was right: He never did forget.

She “would take jobs that she would never want me to know about,” Hamilton, the longtime Seminoles coach, said the day before his team’s victory against N.C. State. He has found himself reflecting more and more lately, now that he’s the longest-tenured men’s basketball coach in the ACC. He has found himself thinking more about his journey and its origin.

Part of it is because people are more often asking about it these days, now that Hamilton is the ACC’s elder statesman — a phrase that makes him pause and chuckle, in a way he often does when something amuses him. Who knows how long Hamilton, 75, will continue to coach. All he can know for certain is that he’s much closer to the end of his career than the start. The arc of it and his life is coming more into focus, the beginning of both growing more distant.

That’s as important a reason as any to keep the memory alive.

“You have no idea what it was like,” Hamilton said of what he endured.

This week in Washington, D.C., he’ll be coaching in the ACC Tournament for the 22nd time. He has faint childhood memories of the tournament’s earliest years in the 1950s, and of listening on a radio in Gastonia to the distant signals from N.C. State’s Reynolds Coliseum. The broadcasts were dispatches from a different world.

Looking for an open door

The ACC of Hamilton’s early childhood, in the mid-50s, was still a decade away from its first Black men’s basketball player, in Maryland’s Billy Jones. Another 20 years passed before Bob Wade in 1986 became the conference’s first Black head coach, also at Maryland. Not that Hamilton knew any different, growing up the way he did.

“As a youngster, I read the paper every day about what was going on in the ACC,” he said. “Bones McKinney. Vic Bubas. ... I was all over Art Heyman.”

In the paper and on the radio, though, all the coverage surrounding the ACC was about white players and white coaches. There was nobody who looked like Hamilton, who knew only of a world of separation and closed doors. And then, in time, knew only of a desire to rise above that world, and create one of his own making.

Approaching the mid-1960s, the papers began carrying stories that brought Hamilton hope. He read about Henry Logan, an Asheville native who in 1964 at Western Carolina became the first Black college basketball player at any predominately white university in the southeast. The next year, Dwight Durante, of West Charlotte High, became the first Black player at Catawba College.

“Before you leave out of here, I want you look up the numbers — the statistics of Logan and Durante,” Hamilton said. “ ... There wasn’t anybody in the ACC better than those two. But they were Black, playing in (their) conference, because they couldn’t play in the ACC.”

It was around the time an up-and-coming young coach at North Carolina, Dean Smith, began recruiting Charles Scott, a dazzling prospect from Laurinburg Institute. Scott in 1966 became the first Black scholarship athlete at UNC, and his arrival there is largely credited with helping to end segregation in college basketball, and in other college sports, throughout the South.

“All I know is that it was huge,” Hamilton said. “It really made a significant impact on the ACC, and sometimes I don’t think Dean’s getting enough recognition.”

At the time, in ‘66, Hamilton was in his first year at Gaston Community College, unsure of anything but his desire to fulfill his goal, and that of his parents, to earn a college education. He thought for a while that the military might be in his future. And though he played basketball at Gaston, there was no way to believe the sport might provide a viable long term path.

‘You control your own destiny’

Hamilton was more than 30 minutes into his story, sitting in his office surrounded by his life’s work — the trophies and the photos and everything else — when he’d peeled back enough layers and found enough comfort to share the details of a turning point. The details of maybe the turning point.

He’d talked about growing up not on a street, but along an unpaved “path,” as Hamilton described it. He’d talked about sharing a small, four-room house with eight siblings, about being a caretaker for four of them. He’d talked about the lack of plumbing, of no hot water and taking baths “in a tin tub in the corner.” He’d talked about the wisdom of his father, if not always the physical presence of a man he described as “a rolling stone,” one who always said, “You control your own destiny.”

“He made me feel that nobody owes you anything,” Hamilton said.

He had talked of the church on the corner of Allison and Morris in Gastonia, the place that gave him salvation and hope; the place that anchored him and made him believe in a greater purpose — that “my steps are ordered,” as Hamilton likes to say. And it was fitting that the church was part of the memory he was about to share, because his mother had taken on another job she didn’t want him to know about so she could buy him new clothes for a Bible School picnic.

That’s what brought the memory back, after all this time. New shoes and Bible School.

And so he went into it, about when his mom was a dishwasher at a downtown diner in Gastonia.

The place was “like a smaller version of a Waffle House,” Hamilton said, and “she never wanted me to come down” and see her while she was working. But one day he boarded a bus and went, anyway. He must’ve been about 12 or 13, he said. He walked toward the diner and the Civil Rights Movement was approaching but had not yet arrived in full. His mom could work at the restaurant, cleaning, but Black people were otherwise not allowed inside.

And so Hamilton stopped at the window and peered inside, at his mother at the sink behind the counter. He could still see her working, her white uniform soaked with dishwater and sweat, a counter of patrons, of white men, at best sitting there, unmoved, and at worst leering.

“And I looked through there,” Hamilton said slowly. “And it made me so sad that she was busting her ass to buy me some pro Ked shoes, some white socks, a pair of pants – I think it was red and white checkered pants. And a shirt, to go on the Bible School picnic.

“There she was, laboring, just to ...”

And he paused for several moments. Some feelings, time cannot erase.

“That was a way of life for us,” Hamilton said. “And I always get emotional, because that was a sign of the times that we had to go through.

“And I felt (like), ‘Gosh – I’ve got to figure out a way of how to be somebody.’”

‘Fulfilling the purpose ... God has for me’

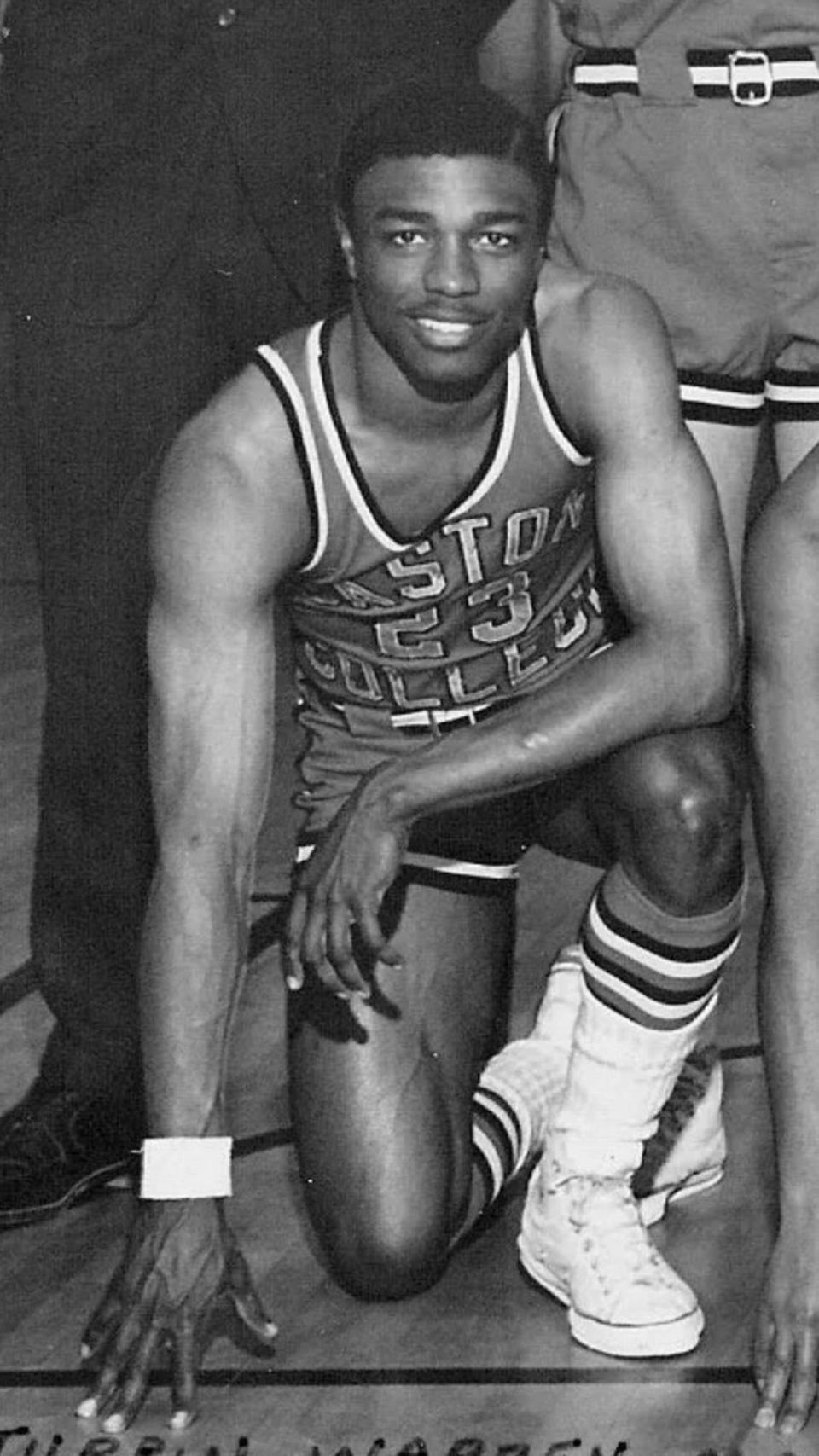

He could’ve been somebody in a number of ways and all of them might’ve been enough. He could’ve gone a different direction, outside of basketball, after he became the first Black athlete at U UT Martin, where Hamilton set a school record for assists and was named “Mr. UTM” by his classmates. He could’ve entered the military, and might have without a chance opportunity that opened a door to coaching.

He could’ve just been an assistant coach at Austin Peay, which had never hired a Black coach before Hamilton forged a path there in 1971, or he could’ve been most known for becoming the first Black assistant coach at Kentucky, where Joe B. Hall hired him in 1974, and where Hamilton helped integrate perhaps the most integration-resistant program in the South.

But he kept going, and going, and “that’s been my journey,” Hamilton said.

“To integrate things.”

He has come now to think of it as part of his purpose, a piece of an ordained mission. He remains tied, in a physical and spiritual sense, to his childhood church. The building is vacant but still standing, and Hamilton visits on those rare occasions he’s back around Gastonia. His church in Tallahassee, Bethel Missionary Baptist, is as much or more a part of his life there as anything that happens on a basketball court, though basketball has afforded him the chance to teach and lead.

“There’s no question that I am fulfilling the purpose that I think that God has for me,” Hamilton said.

He is not only the longest-tenured coach in the ACC but perhaps the most overlooked and underappreciated. Only four coaches in the history of the conference have won more games, overall, than Hamilton’s 420. Those four: Mike Krzyzewski, Roy Williams, Dean Smith and Gary Williams. And only the first three have won more ACC games than Hamilton’s 192, which tied him with Williams for fourth-most conference victories in the history of the league.

Hamilton, who has twice won the ACC Tournament (one of those by default after the pandemic canceled it in 2020), faced a more difficult and unlikely journey than all of them.

All along the way, he has accomplished firsts. First Black athlete at UT-Martin. First Black head basketball coach at Oklahoma State. At Miami. At Florida State.

“To see his story, and for him to be the longest tenured African-American college coach in any sport has never been fired — that’s a testament to his character, and how he’s able to lead with so many people across all demographics,” said Stan Jones, Hamilton’s longtime assistant. “And that takes a unique skill that most people in our society don’t have.”

Paying it forward

Jones has worked on Hamilton’s staff for 28 of the past 29 years. Their bond extends beyond basketball and is fitting, in a way, given their shared history. Hamilton grew up in the throes of integration in the dying but relentless remnants of the Jim Crow South. Jones, meanwhile, is the son of a white Baptist preacher who defied the norms of his time and advocated for the end of segregation. His father was working in Memphis when Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed.

Jones was 9-years-old, and remembers the unrest that followed for days in the city.

“He was one of the first (pastors) who started having minorities come to his churches, and it was not received well,” Jones said. “And I was part of getting the white private school kids in the state of Mississippi to play AAU basketball with the Black public school kids, when that was not a thing that ever happened before. And so I have a sensitivity for that time of what went on.”

He and Hamilton haven’t talked much about it, he said. They don’t really need to.

Their shared history, from different perspectives and vastly different experiences, is an unspoken part of their relationship. And at times, Jones said, “We share those stories with our players, because they need to know.”

And yet it’s impossible to really know what Hamilton overcame to reach this point. When he was a young child, he said, he often asked why. Why did he and his parents have to sit in the back of the bus? Why, when his mother once sat closer to the middle, did a white passenger lean his seat back into her knees, as if to prove a point? Why was it, when his father took the family to Tony’s Drive-In every Sunday, he and his mom and dad and siblings had to eat their hot dogs and ice cream outside, in the parking lot?

Integration began to arrive late in his high school years. As Hamilton remembers it, a football coach at Hunter Huss, which was being segregated, inquired about whether he might want to go there for his senior year.

“I didn’t feel that I was ready to make that adjustment,” Hamilton said. “I guess fear of the unknown.”

He had never known, to that point, of anything other than black and white lines, literal and figurative; barriers that couldn’t be crossed. And slowly they began to fade. Hamilton grew up listening to ACC basketball on the radio and reading about it in newspapers, a sporting and cultural phenomenon sweeping through North Carolina but one that excluded people like him.

He never fathomed he might be a part of it. That one day, he’d be the conference’s longest-tenured head basketball coach, and among its most successful. On his way to becoming somebody — which was always his goal since the day he saw his mom behind that diner counter — he forged a path that nobody ever had, and then kept going a little farther.