Secret of Great Pyramid construction revealed by dried-up river

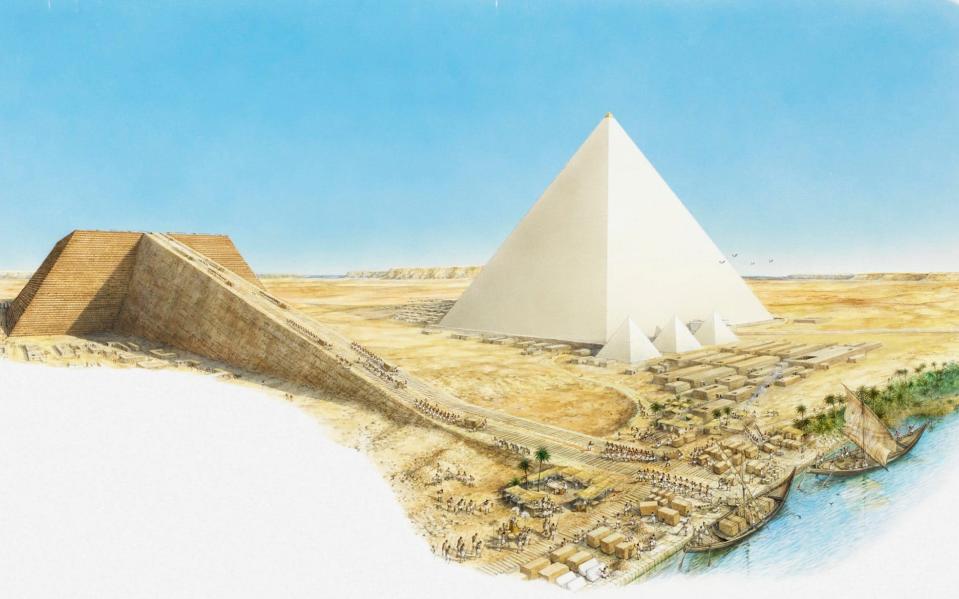

A lost branch of the River Nile was used by ancient Egyptians to transport the enormous stones of the Great Pyramid at Giza, a study suggests.

Egypt’s largest pyramid, one of the ancient wonders of the world and the tallest building on Earth for almost 4,000 years, sits among the largest cluster of pyramids in the African country on a narrow strip of desert.

It has long been a mystery how millions of tonnes of rock were transported to the site to build the pyramids, and the Great Sphinx, on the Giza plateau.

Scientists have now discovered a 40-mile long branch of the River Nile which existed during the time of pharoahs but has subsequently been buried beneath farmland and desert.

The Great Pyramid was built around 2,500 BC by Khufu, a fourth dynasty pharaoh, and the river disappeared some three centuries later, about 4,200 years ago.

The former Nile branch was found using satellite imagery, geophysical surveys and rock samples. Analysis revealed it ran along the foothills of the Western Desert Plateau, close to the pyramid fields.

The scientists, led by the University of North Carolina Wilmington, named the arm of the river the “Ahramat Nile Branch”. Ahramat means “pyramids” in Arabic.

“We suggest that the Ahramat Branch played a role in the monuments’ construction and that it was simultaneously active and used as a transportation waterway for workmen and building materials to the pyramids’ sites,” the scientists write in their paper.

The authors add that many of the pyramids have causeways connected to the extinct branch and it is likely there was a string of harbours along the bank, where building materials were unloaded.

Analysis suggests that the Ahramat branch was pivotal to construction and trade in the Old Kingdom, as five temples (the Bent Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre, the Pyramid of Menkaure, the Pyramid of Sahure and the Pyramid of Pepi II) were “positioned adjacent to the riverbank of the Ahramat Branch”.

The study in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, published by Nature, suggests the Ahramat branch ran close to the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis. It is thought it was turned barren by a 30-year-long drought 4,200 years ago, leaving the arid riverbed under three metres of sand.

“[This] strongly implies that this river branch was contemporaneously functioning during the Old Kingdom, at the time of pyramid construction,” the team write.

Data on water levels and the elevation level on which the pyramids were built show that throughout the Egyptian dynasties, the river was getting progressively lower.

The scientists write: “The enormity of this branch and its proximity to the pyramid complexes, in addition to the fact that the pyramids’ causeways terminate at its riverbank, all imply that this branch was active and operational during the construction phase of these pyramids.”

“This waterway would have connected important locations in ancient Egypt, including cities and towns, and therefore, played an important role in the cultural landscape of the region.”

The scientists say they hope their findings can provide “a more refined idea” of the areas where ancient monuments are located in Egypt and help preserve the country’s culture.

They write: “By understanding the landscape of the Nile floodplain and its environmental history, archeologists will be better equipped to prioritise locations for fieldwork investigation and, consequently, raise awareness of these sites for conservation purposes and modern development planning.”