Search for home of medieval hermit saint leads to even more ancient find in UK. See it

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Saint Guthlac died in 714 A.D., he was already famous for his choice to give up a “life of riches” for years of solitude as a Christian monk.

More than a decade earlier, he had denounced his earthly possessions and joined a monastery, but soon became dissatisfied and instead searched for a watery place to become a hermit.

He found himself in eastern England, in the watery region of the Fens, where he “overcame numerous spiritual battles with demons, monsters and even the Devil himself,” his biographer later said, according to a March 26 study published in the Journal of Field Archaeology.

His body was found a year after his death, which led to a cult-like group of followers who erected an abbey in his honor to house pilgrims coming to see his resting place, the study said.

Uncover more archaeological finds

What are we learning about the past? Here are three of our most eye-catching archaeology stories from the past week.

→ Roman helmet looked like a 'rusty bucket' when it was found in UK. Now, it's restored

→Elaborate 600-year-old castle — complete with moat — unearthed in France. Take a look

→ Mysterious wooden train car — almost 100 years old — unearthed in Belgium, photos show

Despite the reverence of Saint Guthlac, the actual location of his home was never found.

“For years, archaeologists have tried to find its location, and while Anchor Church Field (where the abbey was built) was widely held to be the most likely site, the lack of excavation and the increasing impact of agricultural activity in the area have prevented a comprehensive understanding of the area,” researchers with Newcastle University said in an April 5 news release.

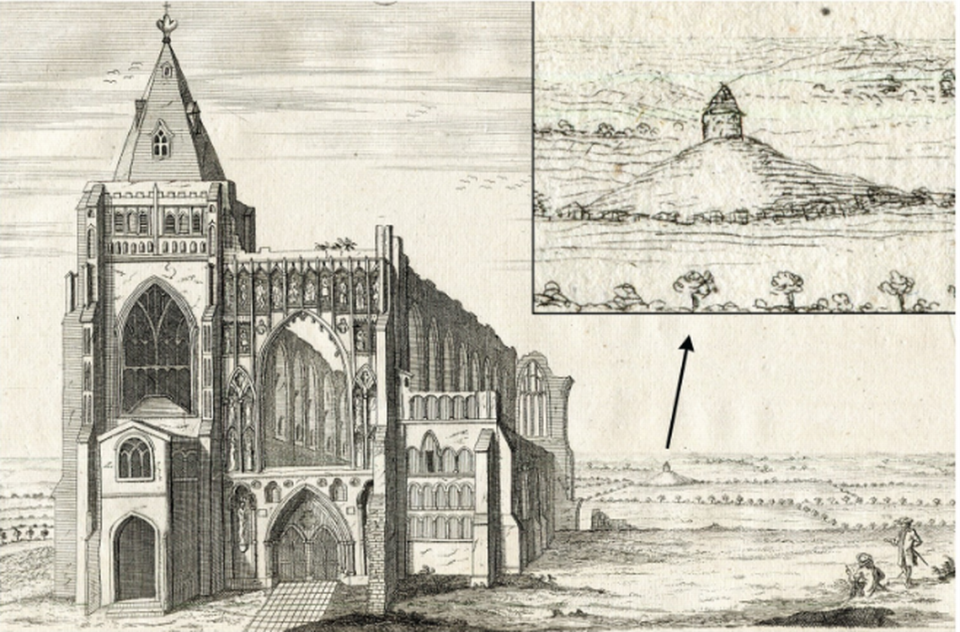

The researchers began excavating the site of the Crowland Abbey, built in the 10th century, in hopes of unearthing the religiously charged land.

They didn’t find Guthlac’s residence — but discovered something much older.

A stone henge was found buried in the field near the remains of the abbey, researchers said.

Dating from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age, which The British Museum says is between 3,000 and 1,600 B.C., the stone circular earthwork is “one of the largest ever discovered” in this region of England, according to the release.

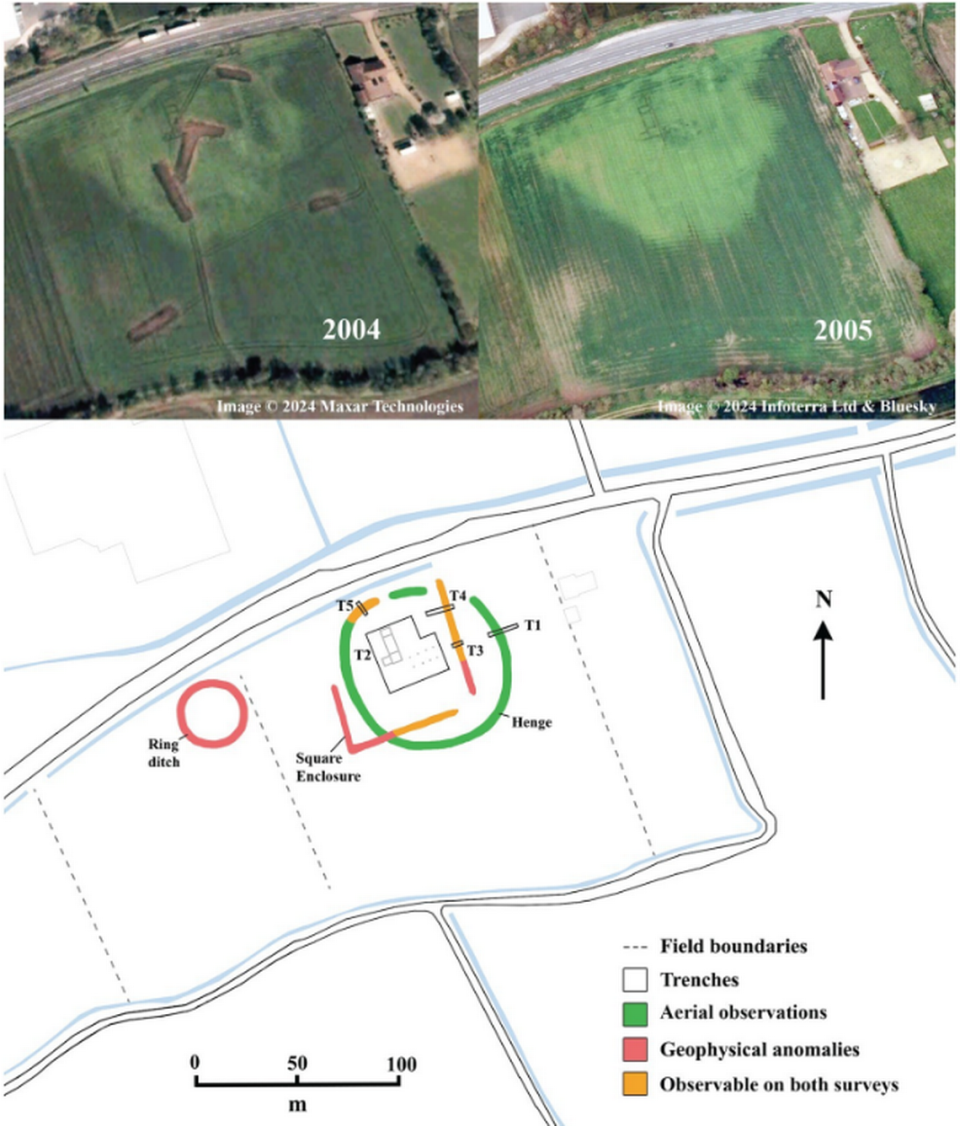

The archaeologists used aerial photographs and satellite imagery to identify the circular impressions in the field, leading to the excavation of one of the trenches, according to the study.

While they were unable to unearth the entire remaining henge, they were able to determine its age and size, one of “truly monumental proportions,” according to the study.

The researchers believe the henge would have been used for ceremonial purposes because of its location on a peninsula surrounded by marshes and water on three sides, they said in the release.

It was then likely abandoned for hundreds of years, slowly degrading, but still visible by the time religious icons were searching for a private place to worship, the archaeologists said. It would have still been visible when Guthlac came to the area to be a hermit, they said.

“It was around Guthlac’s lifetime that the henge was reoccupied, and the excavation found large quantities of material including pottery, two bone combs, and fragments of glass from a high-status drinking vessel,” according to the release.

Over time, however, much of the structure seems to have been destroyed, the researchers said.

“We know that many prehistoric monuments were reused by the Anglo-Saxons, but to find a henge — especially one that was previously unknown — occupied in this way is really quite rare,” Duncan Wright, study author and lecturer in medieval archaeology at Newcastle University, said in the release. “Although the Anglo-Saxon objects we found cannot be linked with Guthlac with any certainty, the use of the site around this time and later in the medieval period adds weight to the idea that Crowland was a sacred space at different times over millennia.”

Crowland Abbey is in a region called the Fens, in central England on the east coast.

Strange horseshoe-shaped monument discovered in France — leaving experts puzzled

Ancient dancing figures — carved on stones in Peru — have psychedelic roots. See them

Complex canal system — up to 800 years old — found under Mexico City. Take a look below

High tide and seaweed hid 3,000-year-old fortress in Ireland — until now. See it