As seagrass die-off accelerates, UNCW researchers hunt for more resilient plants

For some coastal residents and visitors, seagrass is just a nuisance that gets stuck in your flip-flop or wrapped around your boat's propeller.

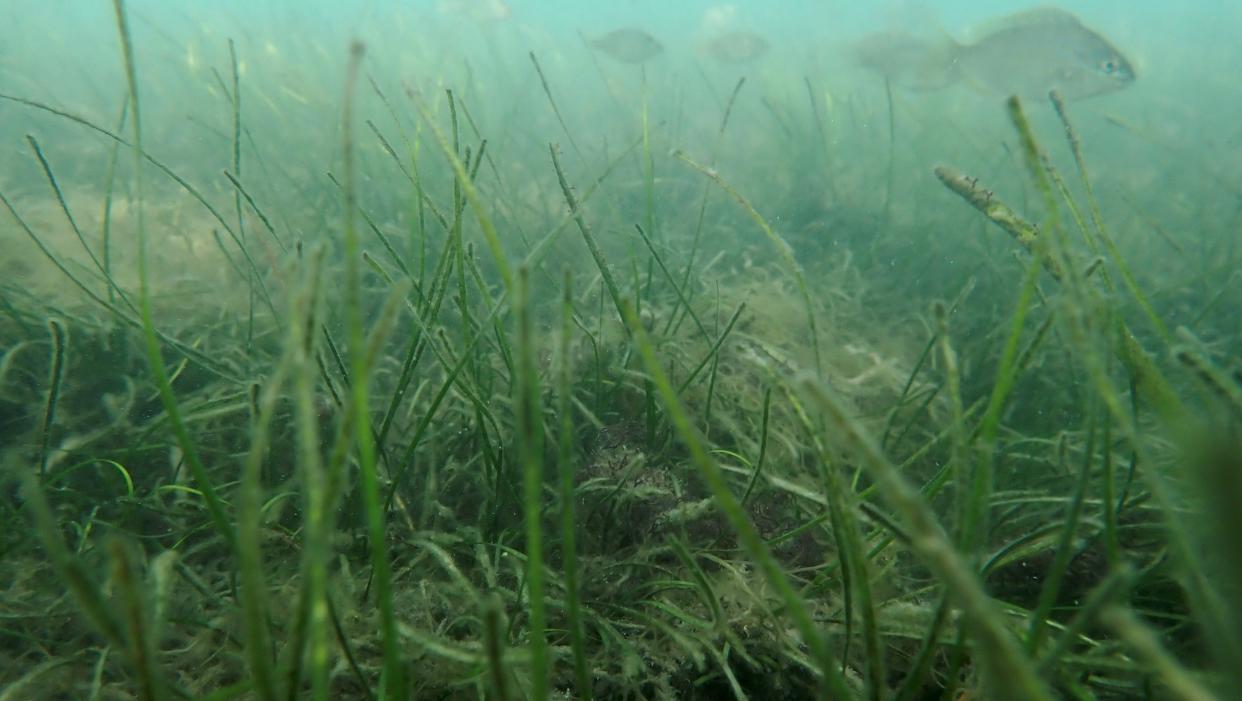

But to biologists, seagrasses provide habitat and nurseries for numerous fish and crustacean species, help improve water quality by holding sediments in place, and are a useful tool in fighting climate change by sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. It also serves as a food source for some species, notably sea turtles, manatees and some fish.

"If you want to find a good fishing spot, you find seagrass," said said Dr. Jessie Jarvis, a coastal plant ecologist at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Yet there's a major problem with these vital ecosystems; the marine meadows that grow in shallow near-shore waters are slowly disappearing.

Warming ocean water temperatures tied to climate change, which add to the woes of low light and declining water quality in many places, have resulted in large-scale diebacks of eelgrass in Virginia's Chesapeake Bay, leading to the loss of habitat and leaving some underwater areas barren of any "structure" or with only thinned fields left. The Chesapeake Bay Program reported a 38 percent decline in seagrass beds in 2019, partly blamed on an increase in river flows into the sprawling estuary. Although aquatic vegetation can often bounce back quickly when environmental factors are favorable, researchers said the die-off amount showed the fragility of the seagrass beds.

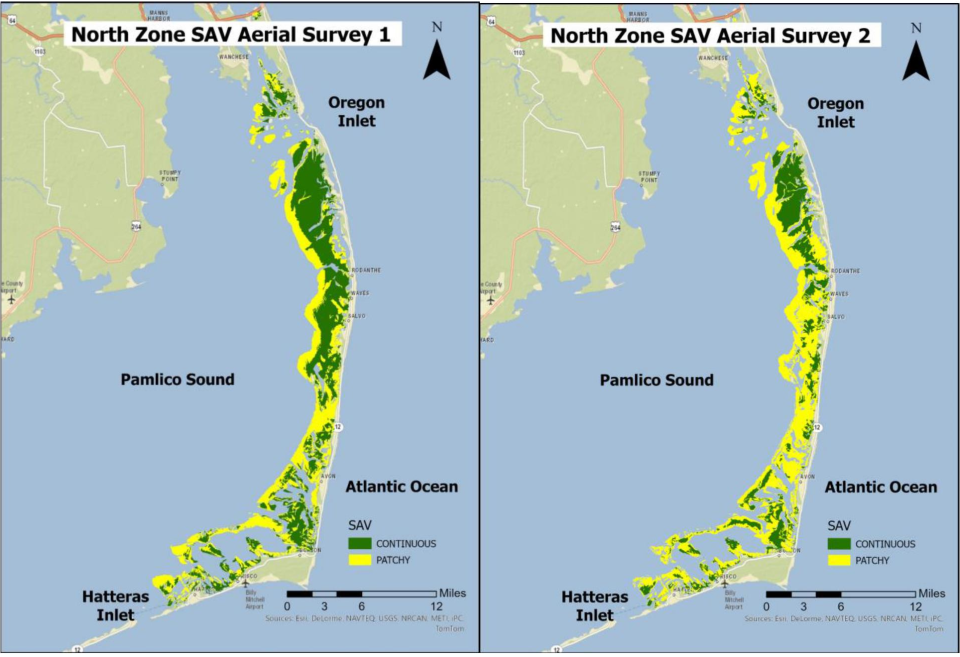

While North Carolina's seagrass population appears to be doing a bit better, it is still declining at the rate of an estimated 1-2 percent a year.

"It's a trajectory that we don't want to see continue," Jarvis said.

But research has found that some seagrasses in North Carolina seem to be better able to respond and react to temperature stressors than other populations along the East Coast.

"If we can figure out the mechanisms of this resilience, then we can see about pre-emptively building that resilience into other populations," Jarvis said.

'Need to do something different'

Jarvis and Dr. Stephanie Kamel, a population geneticist at UNCW, were recently awarded a nearly $400,000 National Estuarine Research Reserve Science Collaborative Grant to help advance their research into why this is so.

Focusing on eelgrass, the scientific duo intend to use tissue and genetic sampling of plants in 10 beds from North Carolina and 10 others from Virginia to see which plants show the most resilience − and potentially why. Samples from the most promising sites will then be tested in restoration sites, with their growth monitored.

Kamel said the aim is to shift from taking seeds or replanting shoots and hoping for the best to a more targeted plan to try and get ahead of the climate-damaging curve by finding plants that are better in dealing with those environmental stressors.

"We need to do something different because what we're doing now isn't working," she said of more traditional restoration efforts.

Eelgrass is one of three species of seagrasses found in North Carolina, which has the second largest seagrass resource on the East Coast after Florida. Found frequently in the state's extensive sounds and near-shore waters along the Outer Banks, the farthest south it has been found is roughly Figure Eight Island in northern New Hanover County.

With water temperatures expected to keep rising in the coming decades − not to mention longer and hotter North Carolina summers tied to climate change, seagrass beds are expected to face increased environmental pressures. Coastal development, especially docks and other over-water structures that can block or limit light, also can contribute to declines in seagrass populations.

Despite the challenges, the researchers said identifying temperature-resistant plants could give existing seagrass beds a head start on preparing for what's coming, since it's always easier to protect existing beds than to try and start from scratch.

"I haven't given up hope yet," Jarvis said. "There's still plenty of time around the year it can thrive."

Reporter Gareth McGrath can be reached at GMcGrath@Gannett.com or @GarethMcGrathSN on Twitter. This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund and the Prentice Foundation. The USA TODAY Network maintains full editorial control of the work.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Grant to help UNCW researchers hunt for more resilient seagrass plants