The scourge of fentanyl: Officers in Great Falls speak candidly about drug crisis

On the last day in April a small group of detectives, sheriff’s deputies, and youth health and welfare advocates made a stop in Great Falls to warn and inform the public about the scourge of fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid destroying lives in Great Falls and across America.

High-profile overdose deaths of celebrities such as Michael Jackson and Prince have brought fentanyl abuse into the spotlight over the last several years, but the drug’s potency and prevalence is often not understood. The law officers from the Northwest Drug Task Force were invited to speak about the drug by Crimestoppers, a citizen organization that allows any community member to anonymously provide crime tips, and possibly be rewarded by up to $1,000 for the information if approved by Crimestoppers Board of Directors.

“We started this fentanyl talk about a year and a half ago because no one was really talking about it. We’d just hear about it on the news,” said Detective Brandon Holzer from the Northwest Drug Task Force.

The task force has jurisdiction across six counties in the far northwest corner of Montana. It consists of just seven investigators who cover a geographic area larger than Massachusetts. Though small and short on resources, the task force has already achieved some impressive victories, seizing close to 15,000 fentanyl pills across its thinly populated jurisdiction in 2022 alone.

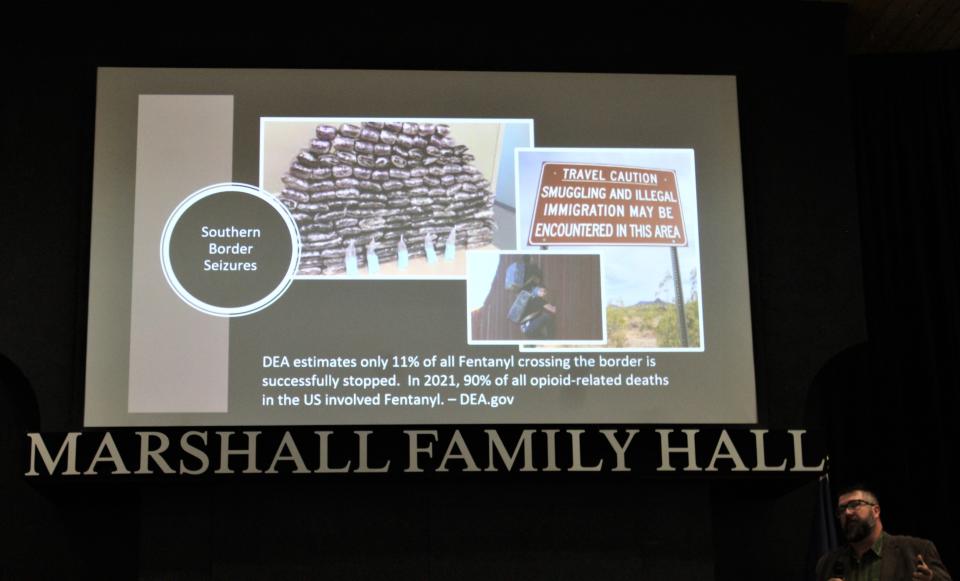

But it’s only a drop in the bucket. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), law enforcement seized "more than 376 million deadly doses" of fentanyl in 2023, mostly at legal crossing points on the border with Mexico. The drug is only rarely transported on foot. It is most frequently hidden in semi-trucks amongst legal imports of food and other retail items, or in private vehicles crossing the border. The amount of fentanyl coming into the U.S. each year is enough to kill every citizen. It remains cheap and readily available.

Opioid overdoses are now the single largest cause of death among Americans aged 18 to 49, eclipsing heart disease, cancer, COVID, and stroke for this age group. In 2023 deaths from opioid overdose, primarily fentanyl, exceeded 112,000 with young people and people of color being the hardest hit. More than 300 Americans die from a fentanyl related overdose every day. Drug policy experts say the magnitude of the fentanyl crisis now exceeds every previous drug epidemic, from crack cocaine in the 1980s to the prescription opioid crisis of the 2000s.

According to the Great Falls Police Department and the Cascade County Sheriff’s Office Montana had 152 overdose deaths in 2022 with 19 occurring in Cascade County. Thus far in 2024 the county has recorded 32 opioid overdoses and three deaths, nearly all are believed to be related to fentanyl.

However, it didn’t start that way. Fentanyl has been around for more than 60 years. It was first developed in the late 1950s for use as an intravenous anesthetic, primarily to provide care for cancer patients. Its production was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1960, and fentanyl remains an important pharmaceutical tool when legally prescribed and properly monitored for the relief of pain and for surgical anesthesia.

The big surge in fentanyl abuse began in 2013 when Mexican drug cartels began to realize the drug’s profit potential. Fentanyl is cheap to make and does not require expert chemists to oversee its production. It is made from commonly available precursor chemicals and does not require the use of vast rural acreages to produce, or months to grow as do other narcotics like cocaine and heroin. It’s neither bulky nor easy to detect.

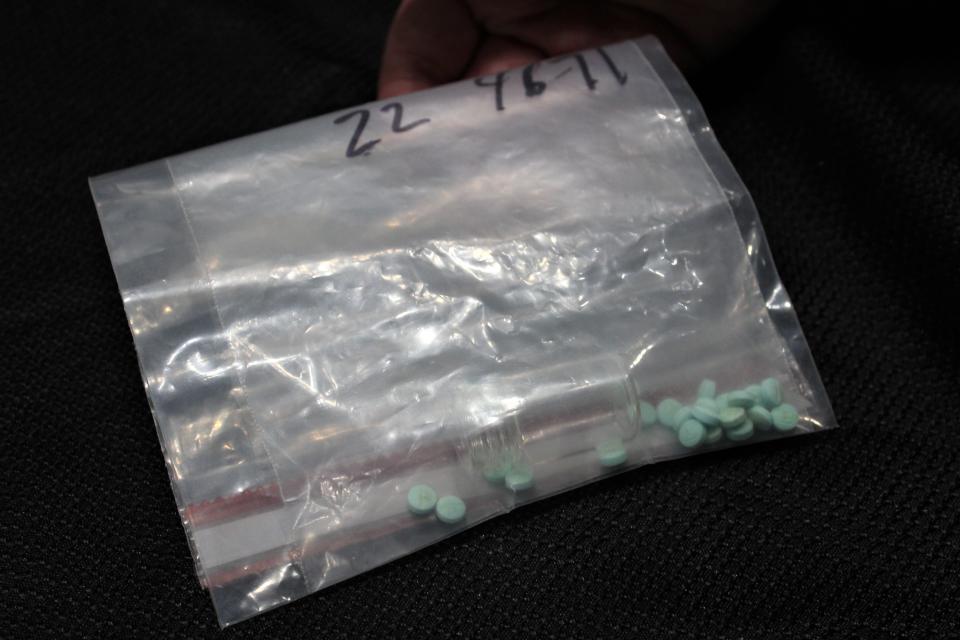

“All the precursors of fentanyl come from China,” Holzer said of the drug’s pipeline into the U.S. “China then ships those precursors to Mexico, and in Mexico they put the components together into a sellable form typically pills that resemble Adderall, oxycodone, or Xanax, but I’ve seen it come in every form of fake pill; Tylenol, Motrin. They design it to look like common over-the-counter medications.”

One of the biggest problems in stopping the flow of fentanyl into the U.S. has been a lack of effective cooperation from either the Chinese or Mexican governments. For years the Chinese government has told the U.S. that its fentanyl crisis is a problem of America’s own creation, and that Chinese companies were under no obligation to halt shipment of the drug's precursor chemicals into Mexico.

In Mexico the disconnect may be even worse. According to Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown, a Senior Fellow of Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution, the Mexican government has denied for years that any fentanyl is produced or eveb used in Mexico.

“I have seen a government that is not willing to confront the cartels in the context where criminal groups are increasing their territorial power, the power over populations, the takeover of legal economies and impact even institutions,” Felbab-Brown said during a presentation before the U.S. State Department.

National Public Radio recently reported that in the past year alone cartel hit men have assassinated at least 20 Mexican political candidates and officials working to halt the production and export of fentanyl in and from their county.

As the drug makes its way north it becomes progressively more expensive, and progressively more profitable. The economies of the drug are making Montana a prime territory for fentanyl distribution, particularly on the state’s Indian reservations.

“On our reservations right now fentanyl is an epidemic,” Holzer said. “The cartel lives on the reservation, and they’re pushing fentanyl that’s killing our Native Americans."

"It’s made in Mexico for less than a dollar a pill," he added. "Then It’s shipped up to the border where midlevel dealers purchase it for $2 to $4 a pill. Then it comes up to Montana. Purchase by users in Lincoln County is for around $18 a piece.”

Holzer said Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel is responsible for most of the fentanyl coming into Montana, and that it can even be purchased on the internet where Dark Web sites like “Onion” and “Tor” will ship it to users directly via the U.S. Postal Service. This despite the Postal Service’s best efforts to interdict as many of these illegal shipments as possible.

“The odds are not in your favor shipping it through the mail, but it does get through,” he said. “(The cartels) will mail it to an Airbnb or anywhere they know someone is not living. Then there will be somebody waiting for the mail on the other side. It either gets delivered or it doesn’t, and they’re okay with loss. It’s just the cost of doing business. It’s okay because there’s always another package coming behind it. There’s always another load driving across the border.”

The most recent wrinkle making the situation even worse is a sharp increase in the use of the drug xylazine to combine with fentanyl. Xylazine is a horse tranquilizer, not approved for human use, which often causes lingering flesh wounds in its users.

“Xylazine basically makes the high last longer and it’s easier to ingest, but it eats your system away,” Holzer explained. “You will die from this eventually, more than likely from infection.”

According to the Wisconsin Bureau of Communicable Diseases repeated use of xylazine can result in severe wounds that do not heal without medical treatment. Protracted infections can result in wounds the turn black, extreme pain or swelling, a bad smell, and fever.

“The Xylazine problem within our homeless communities in some of the bigger cities is taxing our medical staff,” said Holzer. “They’re having go out there to try and help these people, but they’re limbs do not heal. I’ve seen cases where their bone is coming through, and when these humans go through withdrawal when they don’t have it (fentanyl), can you imagine the pain? It’s awful. The DEA’s breakout last year found that approximately 23% of fentanyl powder and 7% of fentanyl pills seized by the DEA contained xylazine.”

So, are there any solutions? Holzer said that beyond law enforcement efforts the most effective tool to halt the scourge of fentanyl in our towns and cities is communication.

“Educating our kids and teens, that’s a big one,” he said. “Have that awkward conversation with your child, talk about it and explain it to them.”

Just as with any suspected terrorist activity one of the cardinal rules is that if you see something, say something. Citizens who witness suspicious activity should call local law enforcement, or they can call the local Crimestoppers tip line at 406-727-8477. An anonymous tip can also be left on the Crimestoppers website at www.p3tips.com.

This article originally appeared on Great Falls Tribune: Fentanyl task force visits Great Falls to discuss growing drug crisis