Scientists could end up flying blind about Arctic sea ice at the worst possible time

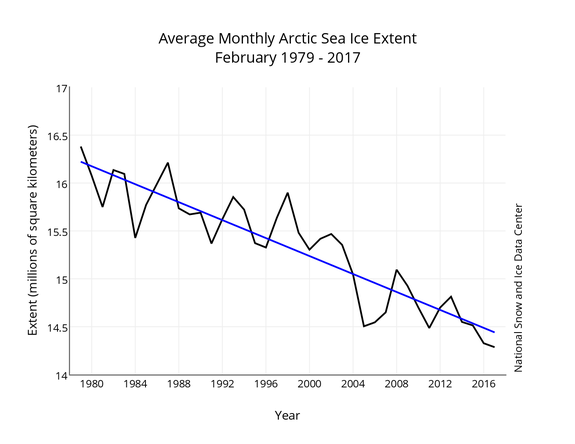

All is not well in the Arctic, where sea ice is in a long-term precipitous decline due to human-caused global warming. In February, for example, Arctic sea ice set a monthly record low, with sea ice extent coming in 455,600 square miles below the February 1981 to 2010 average.

That means that, at the end of February, the Arctic was missing an ice chunk the size of Texas, California and West Virginia combined, thanks to an unusually warm winter and long-term climate change.

That's a lot of missing sea ice.

SEE ALSO: Something is very, very wrong with the Arctic climate

To track sea ice trends, scientists have been using microwave sensors aboard Defense Department weather satellites that pass near the North Pole, but recent failures in key instruments plus delays in planning and launching next generation satellites means we may soon be flying blind in the Far North at the worst possible time.

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado, which tracks sea ice trends, warned in a news release on Tuesday that satellite data gaps may soon cause sea ice observations to go dark for a few years. The specific timeframe they're concerned about is the period between now and 2023.

The reasons for the concern are a little wonky, but they amount to a combination of aging, increasingly unreliable sensors aboard current satellites, a Pentagon decision not to launch a replacement satellite for one that failed on Feb. 11, 2016, and the likelihood that no new satellite with the necessary hardware will be in orbit until 2023 at the earliest.

Last year, a sensor on the Defense Department's F17 satellite that NSIDC scientists had long been relying on for sea ice observations malfunctioned. In response, the NSIDC switched to data coming from a different satellite sensor on another satellite.

The instrument, technically known as the 37 Gigahertz vertical polarization channel, is an important part of the algorithm that allows scientists to measure sea ice extent.

Image: nsidc

However, there are problems involving the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program that has provided scientists with a continuous record of sea ice observations since 1987. (Earlier data from other satellites extend that record back to 1979.)

Last year, the newest sensor, known as F19, went completely dark, causing "grave concerns" to arise about the long-term continuity of sea ice records, the NSIDC said in the release.

Right now, only two Defense Department satellite sensors aboard the F16 and F18 spacecrafts are "fully capable" of providing sea ice observations, and they're aging, having operated well beyond their five-year design lifetimes. Even with the failure of the F19 satellite, Congress instructed the Air Force to mothball a newer craft, known as F20, that the agency had already built.

"An easy fix would seem to be to get the final F-20 satellite out of storage and launch it, but as we understand it, it is to be dismantled," said Mark Serreze, the NSIDC director, in an email. "With any luck, we'll keep limping along with F-18 of F-16 until new capabilities come on line."

American scientists get some help from their international partners, although it wouldn't be a complete solution. Another similar satellite in use by Japan is also approaching the end of its design lifetime, but it provides sea ice extent data using a different technique.

The Japanese data, which is from an instrument known as the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer, or AMSR, is not the same exact information as what comes from the Defense Department satellites, which compromises the long-term record.

Incredibly, we may soon lose our "eyes in the sky" for monitoring rapidly melting #Arctic #SeaIce as gap in satellite coverage looms. https://t.co/xtjwIz9QbI

— Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) March 6, 2017

Similarly, European satellites also help track sea ice, but they do not have the same instruments that the NSIDC researchers have relied upon for long-term records of sea ice trends.

New satellites with microwave sensors used to keep tabs on sea ice extent are not likely to be launched until 2022 at the earliest, the NSIDC says, which "presents a growing risk of a gap in the sea ice extent record."

If a gap does arise, it would mean sea ice data would be less reliable as scientists scramble to figure out how to obtain accurate data from other instruments and speed up the launch of new spacecraft.

Sea ice data gaps may not seem like a big deal, considering that few people live in the Arctic, but with the region increasingly opening up to ship traffic, oil and gas drilling and military activity, having an idea of precisely where ice is can be crucial to ensuring safety and protecting the environment.

In addition, having long-term records of sea ice trends is important for tracking climate change, and ideally scientists would have a yearlong overlap between an old and a new instrument in order to test the newer tool's reliability. The data gap means that may not be possible.

"It is a large concern," said Julienne Stroeve, a senior research scientist at the NSIDC. "When Congress told the Air Force to scrap the last built SSMIS F-20, combined with the failure of F-19, we realized there might indeed be a gap in the data record," she said, using the acronym for the microwave sensor aboard these satellites.

"Ideally it's best to continue the same satellite program so that inconsistencies are not introduced from using a different combination of wavelength bands or different spatial resolutions. But that will not happen now."

Scientists who have been shocked at the rapid climate change taking place in the Arctic, and at this unusually warm winter in particular, say they are worried about losing important monitoring tools that help them determine what's going on.

In short, a data gap would be a setback to climate science at a time when researchers can ill afford it.

"There is no need to panic, but there is growing concern," Serreze said.