Is Scientific Genius Extinct?

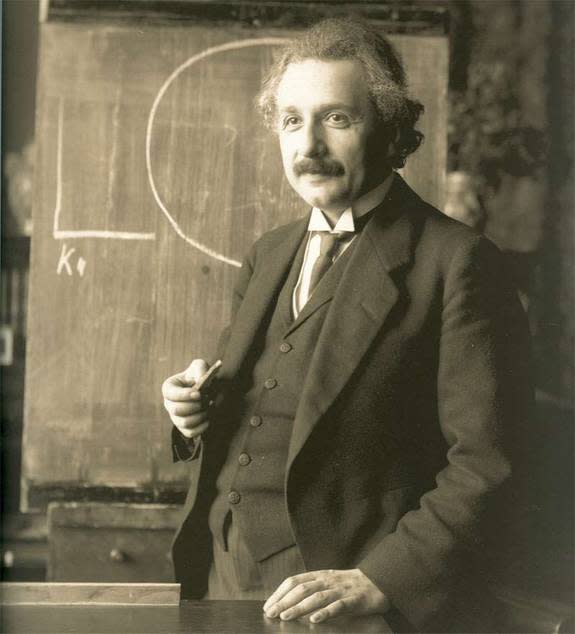

Modern-day science has little room for the likes of Galileo, who first used the telescope to study the sky, or Charles Darwin, who put forward the theory of evolution, argues a psychologist and expert in scientific genius.

Dean Keith Simonton of the University of California, Davis, says that just like the ill-fated dodo, scientific geniuses like these men have gone extinct.

"Future advances are likely to build on what is already known rather than alter the foundations of knowledge," Simonton writes in a commentary published in today’s (Jan. 31) issue of the journal Nature.

An end to momentous leaps forward?

For the past century, no truly original disciplines have been created; instead new arrivals are hybrids of existing ones, such as astrophysics or biochemistry. It has also become much more difficult for an individual to make groundbreaking contributions, since cutting-edge work is often done by large, well-funded teams, he argues.

What's more, almost none of the natural sciences appear ripe for a revolution.

"The core disciplines have accumulated not so much anomalies as mere loose ends that will be tidied up one way or another," he writes.

Only theoretical physics shows signs of a "crisis," or accumulation of findings that cannot be explained, that leaves it open for a major paradigm shift, he writes. [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

Prior predictions

This isn't the first time someone has predicted that science's most exciting days are over.

Before the arrival of quantum mechanics and Einstein's theory of relativity, two theories physicists have not yet been able to reconcile, 19th-century scientists predicted that all major discoveries had been made, Sherrilyn Roush, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, pointed out.

"They didn't see the revolution coming, didn't even see the need for it," Roush told LiveScience in an email, adding, "Above all, revolution and genius, like accidents, are not predictable. You often don't even know you need them until they show up."

She did not find Simonton's argument persuasive, noting that geniuses aren't necessarily crucial for revolutions in thinking, and she questioned the importance he placed on the creation of new disciplines.

"People are dazzled by revolutions and have too little appreciation of 'normal science,' where we accumulate lasting, and often useful, knowledge," she wrote in the email.

Coping with increasing information

While he sees diminished opportunity for genius, Simonton says that the demands of science are increasing.

"If anything, scientists today might require more raw intelligence to become a first-rate researcher than it took to become a genius during the 'heroic age' of the scientific revolution in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, given how much information and experience researchers must now acquire to become proficient," he writes.

Roush agreed, saying that nowadays reading all of the literature published in a particular field may no longer be possible.

Individual researchers, and human society, in general, may be adapting to the increasing demands by redistributing the work both to other people and to computers, she told LiveScience.

Given the increasing use of computers to process information, “who knows that the ability to see it all and abstract to new ideas is not increasing?" she wrote in the email.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter@livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.