Science at work in the age of coronavirus: What will we learn from it?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Americans of a certain age — the same age as the ones who are most at risk from the coronavirus, as it happens — might remember reading “Arrowsmith” in high school, or even seeing the 1931 movie starring Ronald Colman and Helen Hayes. The novel by Sinclair Lewis, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1926, tells the story of an idealistic young doctor during an epidemic of bubonic plague, forced to choose between doing rigorous research on a possible cure, or just treating all patients with it and hoping for the best.

The advantage of the former course is that it could prove, or disprove, the efficacy of the treatment, advancing scientific knowledge and saving many lives in the future. By the same token, if the treatment doesn’t work, better to know it sooner rather than later. The downside is that the only way to find out for sure is by not giving the treatment to some patients, who (if the disease under study is bubonic plague) are likely to die.

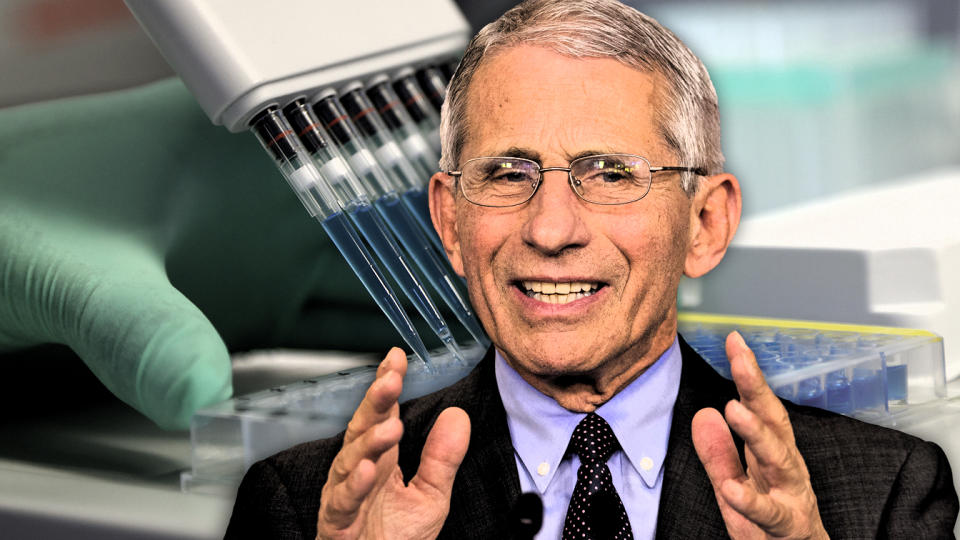

This dilemma from a century ago is playing out now in public in the alternating appearances in the White House briefing room by President Trump and Dr. Anthony Fauci, the infectious disease specialist on the administration’s coronavirus task force. At issue is a drug called hydroxychloroquine, which in combination with the antibiotic azithromycin seems to have speeded the recovery of a small number of COVID-19 patients. The evidence is what scientists call an “anecdotal” report. Another example of an anecdotal report is “I took my umbrella to work yesterday and it didn’t rain.” Would you put your life in the hands of someone who makes important decisions on that basis? There is a reason for the saying among scientists that “the plural of anecdote is not data.”

Fauci wants to study hydroxychloroquine in a systematic way to determine if it is safe to take for the coronavirus — and if it actually works. (It is approved to treat malaria and diseases such as lupus, although it sometimes has serious side effects.) Trump for his part has been excitedly talking it up to his national audience, belligerently demanding of skeptics, “What do you have to lose?”

As a result, the American public is being treated to a real-time illustration of the scientific mind at work. The gold standard for the kind of study Fauci has in mind is the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Hundreds, or even thousands, of patients are randomly divided into two groups: one to receive the drug being studied, the other to get a dummy pill with no active ingredients (or an existing treatment for the same condition, to see if the drug under study works better). Both the subjects and the researchers running the trial are “blinded,” meaning they don’t know who is in which group. That controls for the “placebo effect” — the tendency of patients to report (or even legitimately experience) improvement from just the experience of being treated — and is meant to eliminate the risk that the results were tainted by unconscious bias or wishful thinking by the researchers.

At the end of this process, the data is compiled and the outcomes of the two groups are compared and adjusted to account for random differences (e.g., patients in one group might be, on average, older) and then put through a form of mathematical waterboarding called the P-test. And then if the results pass the threshold of “statistical significance,” the researchers write up the experiment in a paper and submit it to a scientific journal, which sends it out to other scientists in the field to review and comment, and then it is published and if the Food and Drug Administration is satisfied, the drug can be brought to market.

Of course, it’s actually much more complicated than that. Such a study on a new drug may take several years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars. But that is how science works, as distinguished from other ways of dealing with a deadly pandemic, such as denouncing it as a hoax or a conspiracy, wishful thinking about it disappearing by Easter, drinking bleach or “executing judgment” on COVID-19 in the name of Jesus.

This is not to say that hydroxychloroquine — or, for that matter, putting your hand on your TV screen while a televangelist prays for your healing — doesn’t work. Maybe they do, maybe they don’t: The only way to know is to run an experiment.

Beyond that question, though, one can ask if this exposure to science as a concrete, life-or-death matter, rather than something you had to take in high school, will have a lasting effect on attitudes toward a discipline that millions of Americans despise as a fount of godless evolutionism, job-killing climate alarmism and reckless misinformation about vaccines.

“It’s an interesting question,” says Joseph O. Baker, an associate professor of sociology and anthropology at East Tennessee State University who studies American attitudes toward religion and science. Baker has found that rejection of evolution — a fundamental principle in all biology, including the study of germs such as the coronavirus — is a shibboleth of the right-wing movement he calls Christian nationalism, a belief that is unlikely to be shaken even by a deadly pandemic. Natural selection can be proven empirically, but the question of human origins isn’t amenable to experiment. He came to a similar conclusion about resistance to climate science, which is rooted in the economic interests of key Republican constituencies. Applying a controlled experiment to global warming would require a second Earth, which unfortunately isn’t available.

But there’s another manifestation of scientific skepticism that doesn’t depend on the Book of Genesis, or the economic prescriptions of the Club for Growth: the rejection of vaccines, which Baker says is associated with conspiratorial thinking by “truthers” who see hidden agendas and disguised motives behind every unsettling development in the world.

“If they develop a vaccine for coronavirus, do the anti-vaxxers keep on that path?” he muses. “I would hope it would change people’s minds. It’s one thing to reject science in the abstract and another if a family member gets sick and dies.”

Confronting mortal peril, as Samuel Johnson reminded us, concentrates the mind. It is a commonplace saying that there are no atheists in foxholes. What the coronavirus may tell us, eventually, is whether it is also true that there are no truthers in ICUs.

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please reference the CDC and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more: