'This school ... saved me': Discovery Program at Centennial High serves as national model

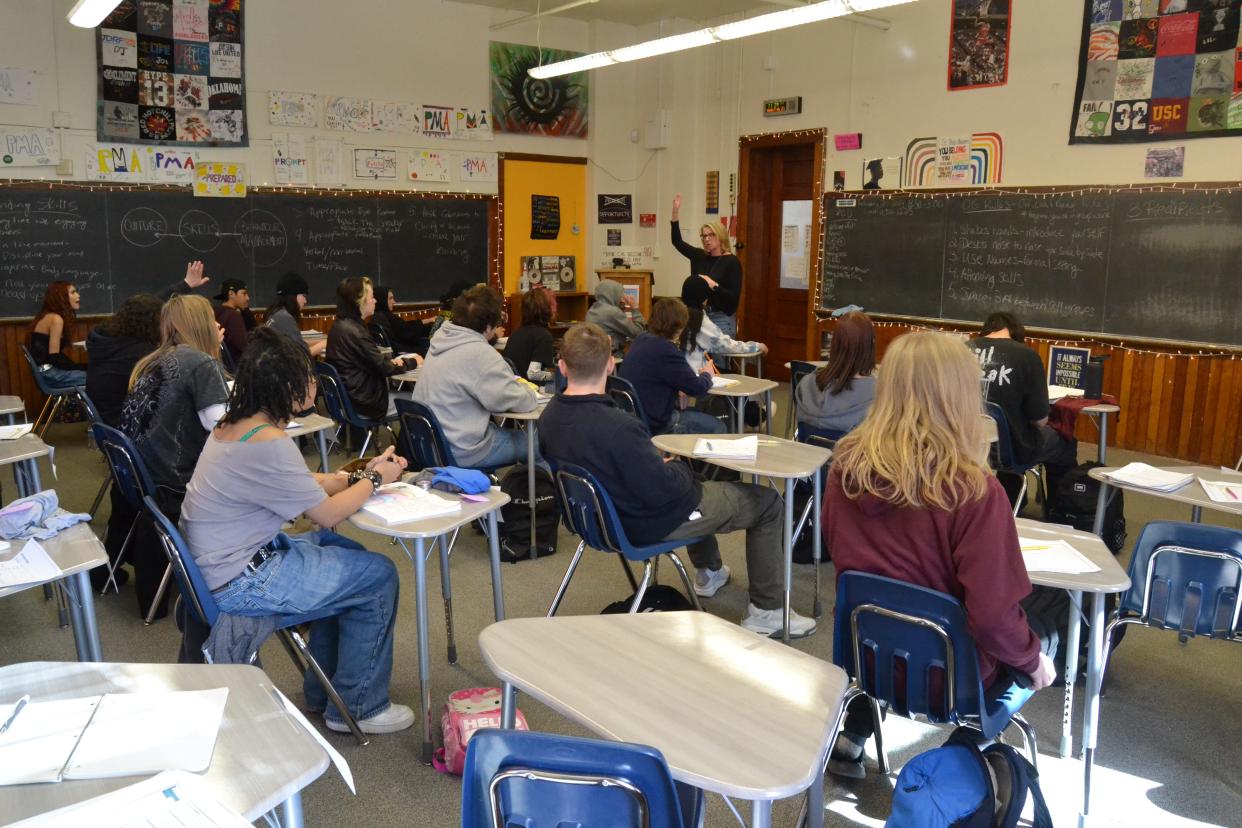

Students listen intently, some taking notes, some doodling on pieces of paper, as three different teachers take turns introducing key points of the Discovery Program to students new to Centennial High School.

Jacqui Walz and Galynn Lackey, both deans at the alternative high school, and a visiting teacher from the Adams 14 School District, Justin Clyatt, discuss the six essential skills “that we believe every young adult needs to be successful,” Walz explains later.

Those skills — working effectively and cooperatively in groups; anger management; transactional analysis; assertiveness training; problem solving; and conflict resolution — provide the foundation.

That foundation isn't just for the Discovery class. It's for everything these students will learn and do while pursuing their high school diplomas at Centennial, one of Poudre School District’s two alternative high schools and the birthplace of the nationally recognized Discovery Program.

“We give them the skills before they need them, so when they do need them, they can use them instead of going down a different path,” said Blythe Johnson, now in her fourth year as Centennial’s integrated services teacher and 10th year in PSD. “I think that’s what sets us apart. We actually give them real-life skills, 21st-century skills, which helps prepare kids for life in general.”

All students at Centennial, which has an official enrollment of 143 this year, must successfully complete the Discovery class before they can move on to the school’s five-period academic day, where they will take the classes required in English, mathematics, science, social studies and other subjects to earn their high school diplomas.

“It’s the syllabus of the school,” Lackey said. “It’s where we teach the six essential skills that we use to do life every day here at Centennial, and that we hope transfer out into the world to help them. Essential skills that humans, that human adults need to be successful in school and in life.”

Centennial is ‘mothership’ of nationally recognized Discovery Program

Centennial has a strong track record of success since its start in 1976 as a night school for adults wanting to complete their high school diplomas. It became a full-fledged alternative high school in PSD in 1989 and soon after adopted the Discovery Program, created by one of its teachers, Eric Larsen, in 1990.

Larsen and fellow teacher Bryan Maddox worked with education researchers at Colorado State University to implement an earlier version of teaching important life skills to students at Centennial — Positive Alternatives to School Suspension, or PASS — that grew into Discovery, said Dierdre Cook, a teacher at Centennial’s former middle school from 1983 to 1987 who returned as the high school’s principal from 2002 to 2005.

“Everything I know about what was good for kids, I learned in the building while I was at Centennial,” said Cook, who spent more than 30 years in PSD schools as a teacher and administrator before retiring in 2013.

Centennial's Discovery Program, which is now threatened by school consolidation and closure plans as PSD addresses declining enrollment and the associated funding reductions, is now used in schools in more than 20 states, its website touts. And it’s continuing to expand. Centennial often hosts teachers and administrators from school districts across the state country who want to learn more about the program and see it in action.

“This is really the mothership of the program,” said Clyatt, the visiting teacher from Adams 14.

That’s why Clyatt was in the classroom working with Walz and Lackey to get a group of students new to Centennial started on the second day of the six-week course. His school district, Adams 14 in Commerce City, is bringing Discovery to its alternative high school, Lester Arnold, on a small scale this spring with a full launch planned for the start of the 2024-25 school year. Clyatt is the school’s first Discovery teacher.

“We were looking for something that has, obviously, a proven method; that’s part of why we looked at Centennial High School,” said Garrett Douglas, Lester Arnold’s principal. “It’s been one of the premier providers of this for 25 years. It’s already tested, it’s research-based, and it has a good amount of structure to it.”

That structure is Discovery.

Students attend Centennial by choice

Students sign a pledge at the end of their first week in Discovery, vowing to adhere to the six essential skills. They recommit to it by signing the Centennial Pledge at the start of each school year, Walz said.

Students who choose Centennial — often a last resort for those who have struggled at other high schools — must first go through an admissions process that includes an orientation session, a letter of recommendation and an in-person interview. The school’s two counselors and administration meet to discuss the applicants and then extend offers to those they believe can be successful there.

“There’s a reason why there are students who take Disco, and if they don’t pass, they’ll take it like six times,” art teacher Andie Cobb said. “It’s because they want that, and that is a goal for them.

“At the end of the day, it’s their choice, and because they all have that shared culture and shared language, when they enter my classroom — this is the first time I’ve been able to do my job, ever — I actually get to teach and not just douse fires all day.”

More: Small enrollment, big impact: PSD mountain schools are hubs of three communities

Centennial students say the school has flipped what they see as the typical high school dynamic. Teachers, they said, are there for them, rather than the other way around.

"They're more interested in my education, not, like, the curriculum they have to meet," said Clara Dusek, a transfer from Fossil Ridge High School.

Added Poudre High transfer Halyn Davis: "They make sure you understand it, and not just the formula and this is what you have to do, but this is why you have to do what you have to do."

Who are Centennial’s students?

Most students come to Centennial from other high schools in Fort Collins that weren’t working for them. Some didn’t feel safe in schools with 1,500 to 2,000 students in the building, while others took advantage of the anonymity those settings offered and often skipped class.

“I was at Poudre High School for my freshman year,” 2019 Centennial graduate Haley Garcia said. “I didn’t really go to school, though. My mom would drop me off, and I would leave with my friends, and then she would pick me up again at the end of the day.”

Lia Cozad, who is on track to graduate in May after two years at Centennial, said she was “kicked out” of Rocky Mountain High School for excessive absenteeism.

Kam Hansen and Davis, who were part of the same Discovery class as Cozad when they first arrived at Centennial, said they never felt comfortable or connected while they were attending Poudre High.

“I did not like my old school at all, not one bit,” Hansen said. “I feel like this school definitely saved me. I genuinely don’t think I would have graduated if I didn’t come to Centennial.”

For Dusek, the move to Centennial was more about a smaller school with smaller classes. Her brother had gone to Centennial, she said, and it seemed like it would be a good fit for her, too.

She’s not just on track, she’s about to graduate a year early thanks to the additional classes she has been taking through PSD online programs to supplement Centennial’s five-period academic day.

“I think education is very important,” she said. “But the structure of school is stressful for me, so I want to get out of here as soon as I can.”

Centennial’s enrollment is small by design

A key element of Discovery, though, is the personal relationships students and staff form in a small-school setting with smaller class sizes, current and former students and staff said. Centennial’s enrollment is capped so that the total number of students and staff doesn’t exceed 200, a limit based on research Larsen and Maddox reviewed while setting up the program.

“Centennial was designed specifically with that research in mind, that human beings only have the capacity to build relationships with so many people at one time,” Lackey said. “Here at Centennial, they’re not going to know everybody super well and have relationships with every single person. But they can recognize them.”

They’re quick to greet the new students getting their starts in the Discovery class, “and know when there’s an outsider coming in and if that person is even supposed to be here on our campus or not. That’s part of how we stay safe, and how our kids stay successful in school.”

Accountability is part of that equation, too.

More: Poudre School District pauses school consolidation plan, seeks community input

In a school the size of Centennial, there is no anonymity. Students know almost as well as the teachers do who is and isn’t in class on a particular day, and they know there are people who are going to check up on them and inquire about their well-being throughout the day.

Johnson said a lot of Centennial students have told her when they didn’t go to class at their previous schools, “no one cared."

"Here, they know that someone cares, that someone is going to check in on them at least one time a day if not five with every single teacher, and I think that keeps them coming back," Johnson said. "I’ve had so many kids say, 'I just come to school so I can check in, and I come because you’re here,' and I think our community does that for them.”

Average class sizes are in the mid-teens, giving teachers the opportunity to work individually with students as needed without sacrificing the progress of the class as a whole, said Kim Donegan, a math teacher now in her 21st year at Centennial.

“For me, to hang out with 16 kids for an hour and a half, we can get a lot accomplished,” Donegan said. “And I still feel like I can know at the end of every period almost — maybe not every single period, every single day — but know where each kid is. How far did we get?”

Centennial follows a different academic schedule

Classes at Centennial are taught in six-week increments, called hexters, rather than the nine-week quarters other high schools in PSD are now using or traditional 18-week semesters. Shorter academic terms were a common theme found in programs that were working for high school students around the country when Centennial’s early leaders were setting up the daytime program, Lackey said.

“Kids are able to see the light at the end of the tunnel,” she said. “So, when life outside of here gets hard or hectic, if the academic grading period is too long, they might just throw in the towel. ‘Home is hard, life is hard, and now school is hard; I’m done. I throw in the towel.’

“But when the window was a little bit shorter, like around week four of the hexter, their life might be getting stressful or difficult, but they’re like, ‘I can make it through. I’ve got two weeks left. I can do this.’ ”

The hexter is a proven “academic intervention” for at-risk students, based on the idea that “you can do anything for six weeks.”

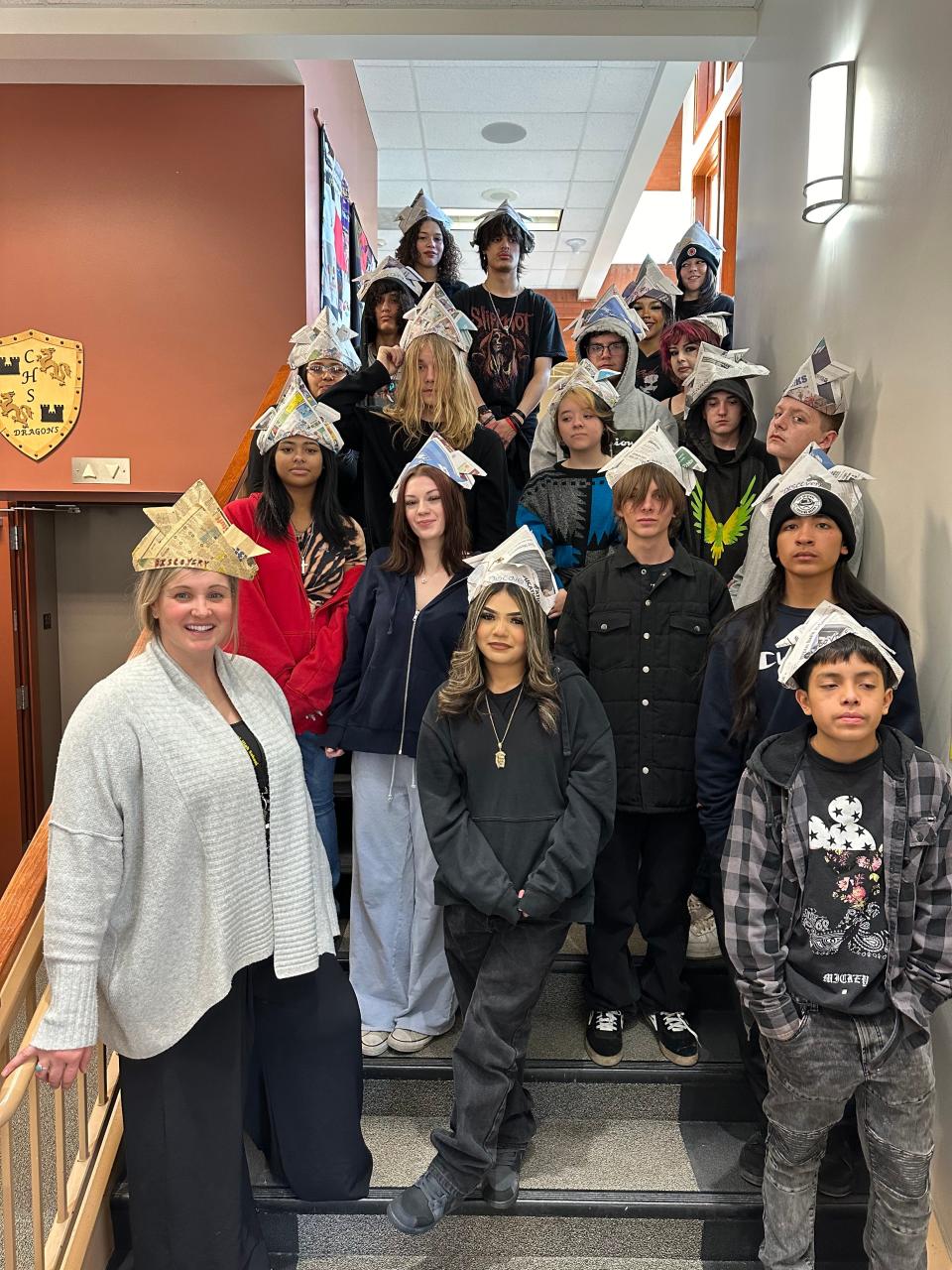

Stairway graduation ceremonies, where all students in the school line up along the historic school building’s main stairway for a celebratory photo, are held at the end of each hexter.

And then they get a fresh start, with a whole new set of classes for the next six weeks.

The school went to a four-day instructional schedule, with classes taught a little bit longer each Tuesday through Friday, in 2019. The extra day off allows students the opportunity to work extra hours at their jobs, or a day to see doctors or dentists or for other appointments that would otherwise interfere with the school day.

The Monday of the last week of each hexter, Walz said, is a “learning Monday,” with a shortened school day to ensure Centennial still meets the Colorado Department of Education’s required minimum of 1,080 instructional hours each year for high school students.

More: What we know about Poudre School District's proposal to change graduation requirements

And the last two days of each hexter are set aside for students to participate in short elective courses they wouldn’t otherwise have access to, given the size of the school and its staff. Some are more academic than others, Walz said, noting that a local astronomy group provides telescopes and helps teach students about stars and planets. Other classes have gone on trips camping in Colorado’s national parks or to Denver Nuggets games or skiing and snowboarding. One popular option, she said, is a sleepover in the school building “to try and catch the ghost.”

Students gain elective credits for many of the classes. But more important, she said, is the opportunity it provides to further build relationships and community in a safe place.

Students view Centennial as a safe space

Teachers and other staff at Centennial are taught through the hiring process to avoid judging students based on their actions, appearance, speech patterns or anything else that’s “outwardly showing,” teacher Alex Dziaba said.

“I think our students have so often been immediately judged for every part of their being, and we just don’t do that here,” he said. “We’re really good at not doing that.”

Students are reminded on the first day in the Discovery class that they came to Centennial for a fresh start, and so did everyone else in the room. The skills they’re taught, including conflict resolution, are used throughout the building, and Lackey said she can count on one hand the number of physical fights that have taken place in her 17 years at the school.

“Since we see the same, like, 70 students every single day, that leads to a lot more friendliness, connection and just, like, a positive environment,” Hansen said. “I feel like no one is really singled out, no one is really truly alone here, and that’s something I definitely struggled with a lot when I went to Poudre, was feeling so alone and outcasted and ostracized. That has never ever, ever happened here because of the small sizes, and the fact that everyone knows each other kind of adds on to how Centennial’s just like this big family.”

Centennial has made historic building its home

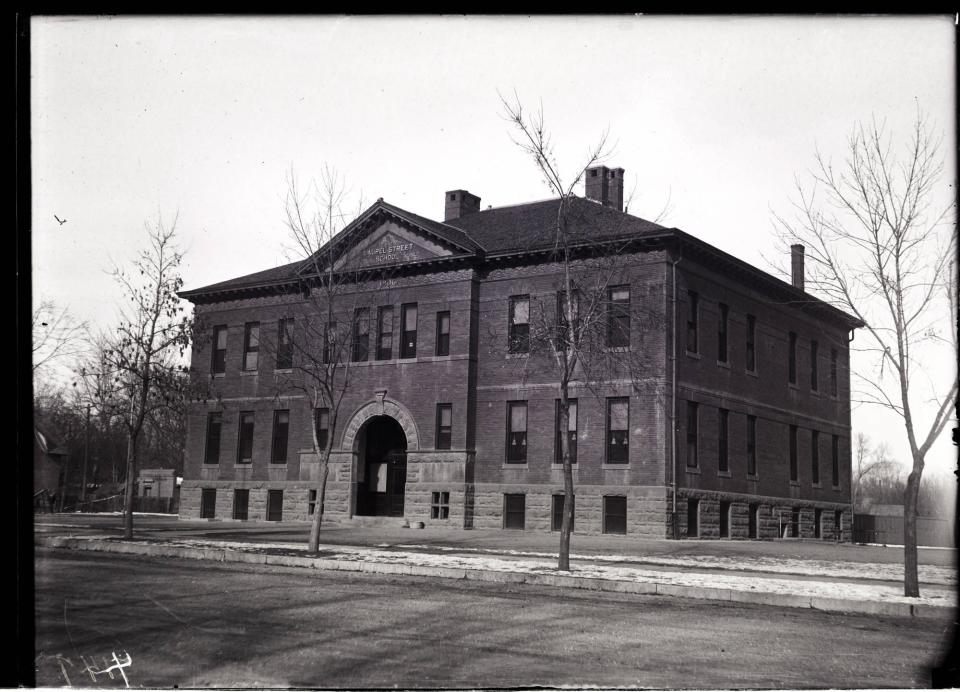

Centennial is housed in the building of the former Laurel Street School, the oldest standing school in Fort Collins that was built in 1906 to 1907, according to a historical look at PSD prepared by the city of Fort Collins, Larimer County and the school district and published in 2004. A $5 million addition to the school in 2002 provided new spaces for science, vocational education, art and physical education, said Cook, Centennial’s principal from the 2002-03 school year through the 2004-05 school year.

More: Do you recognize these Fort Collins sites on the National Register of Historic Places?

The central location on Laurel Street, just two blocks east of CSU and three to four blocks south of Old Town Fort Collins, is easily accessible through public transportation and close to many employers who hire students for after-school jobs.

The eclectic neighborhood, with homes in a variety of styles, sizes and colors, fits Centennial well, Cozad said.

“When I think of this massive public high school in this blank neighborhood, all of the houses are the same, you don’t know your neighbors; there’s no connection. But when I think of here, I think of a bunch of colorful houses, sweet neighbors like a bunch of friends. There’s so much love and care here and support.”

The walls are lined with quilts that every student had a hand in creating during their Discovery class, and the stained glass between the old building and new addition was created by students, too, Cook said.

“It’s a place where at least three generations of students who didn’t thrive at other schools have come to get their high school education,” Cook said. “That’s what Centennial has been for 60 years. You can’t move that to another building," referencing PSD's initial plan to combine Centennial High School and Poudre Community Academy. After protests and community outcry across the district, that plan was put on hold so the district could seek more feedback.

“It’s kind of a sacred place," Cook said. "… If they repurpose that building, it would probably be the biggest educational loss that PSD has had in 70 years.”

How do you measure Centennial’s value to the community?

The administrative and teaching staff at Centennial understand the financial concerns of PSD leadership and its Board of Education as it addresses declining enrollment and the funding reductions that will bring. But the value of individual schools and their educational models should be about more than just enrollment numbers and building capacities, Lackey said.

“I know we hear that we have to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars, which I agree with all day, every day,” she said. “I say to my students, I have to be a great teacher and these skills I’m teaching you have to transfer even outside of here, because citizens of Fort Collins, taxpayers, are expecting me to do that. …

“The bigger thing that I don’t think any of us actually knows is the cost, literally, financially to our community if we go away, because nobody knows the number of people we’ve kept from incarceration, the number of people we’ve kept from serious needs from a facility — all of those things, where our taxpayer dollars go to other entities."

Added Walz: "The cost of a dropout is significant in any community."

Reporter Kelly Lyell covers education, breaking news, some sports and other topics of interest for the Coloradoan. Contact him at kellylyell@coloradoan.com, x.com/KellyLyell and facebook.com/KellyLyell.news.

This article originally appeared on Fort Collins Coloradoan: Centennial High Discovery Program a model for alternative education