Scenes From Trans Activist Cecilia Gentili’s Funeral as Mourners Fill St. Patrick’s Cathredal

Oscar Diaz reaches out to Ceyenne Doroshow and Peter Scotto during the funeral services for Cecilia Gentili at St. Patricks Cathedral in New York City, on Feb. 15, 2024. Credit - Laurel Golio for TIME

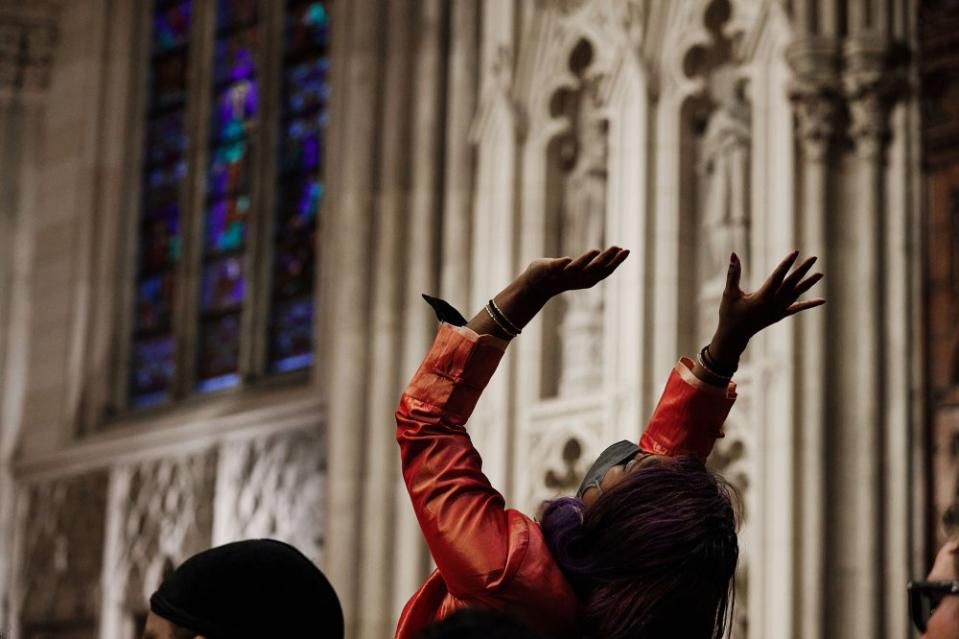

The pews of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City are a sea of black and ruby red that glimmers when the light hits just right. The shine stems from the various gems adorning attendees—on their slicked back, curly shags and mullets, delicate lacy veils, button down shirts, crocheted crop tops, and even decorated in the shape of a heart on the side of their cheeks—who arrive with red carnations and roses to commemorate transgender activist Cecilia Gentili.

The pearls and tulle worn at Gentili’s funeral are what Oscar Diaz, who identifies Gentili as their mother (a part of their chosen family), says best honors her “fabulous” legacy. “It felt appropriate to send her off in this way, to give her her ‘sainthood,’” they say. Gentili is believed to be the first trans woman to have a funeral service at St. Patrick's Cathedral, according to her funeral organizers.

It is no small feat that Gentili’s funeral was held at a Catholic cathedral that has not only hosted services for the greats—like Celia Cruz, Babe Ruth, Andy Warhol—but also symbolizes an institution that has isolated many queer folks from its doors. Whispers of conversation can be heard throughout the cathedral, with some mentioning how long it's been since they’ve attended mass. And when the priest does a call and response, it's not clear whether people do not reply because they are choosing not to, do not know how to, or perhaps don’t remember how to respond.

But regardless, the church on Thursday is packed by the hundreds, where the processional hymn fuses with the clicks and clacks of five-inch heels worn by some guests as they shuffle into their seats. “Cecilia died with Christ,” says Father Edward Dougherty, administering the service for the 52-year-old, after actor Billy Porter sang "This Day.”

Gentili was a pillar in New York for her work on two state bills that helped provide trafficking victims with relief and ended the “walking while trans” ban—an anti-loitering law that police used to harass trans people—but her impact extends much further.

She learned how to build community and create coalitions on her own after arriving in the U.S. as an undocumented immigrant from Argentina in 2004, during which she turned to sex work and developed a drug addiction before being granted asylum eight years later. Since then, she’s devoted her work to others.

Gentili was also a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for attempting to limit transgender people’s access to healthcare in 2020. Her advocacy for sex workers and transgender folks led Gentili to work as the managing director of policy at Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), a leading provider of HIV/AIDS prevention and care, put her on the board of organizations like Alianza Translatinx, a California-based organization advocating for trans inclusivity, and earned her the honor of having a New York City-based healthcare clinic for sex workers named after her.

Outside of her work, people recall her friendship. “She was my confidant,” says activist Ceyenne Doroshow, outfitted in a purple sequined dress and matching veil. “She was the person I could tell ‘I don't like the people I worked with. I like the people I worked for,’ which is the community.”

The care for Gentili is seen in the way some of the guests, like trans indigenous activist Li Aan Sanchez, have traveled more than 700 miles to be present. It is noticed in the way others, like Bobbi Schiavone, 62, came to the funeral despite only knowing Gentili by name and advocacy.

The service is somber but cheerful. To friends she was chef, business woman, playwright, entrepreneur. To many more she is madre, mother, p*ta (wh*re)—as the remembrance cards passed around during her funeral say—, actor, and author.

“To be around Cecilia [is] to feel like you were going to experience the most hilarious moment of your life, but in the process also figure out all of the ways to care for community and map out strategies of community care,” Chase Strangio, Deputy Director for Transgender Justice with the ACLU, says.

Throughout intervals during the service, chants of “Cecilia!” echo inside the 87,120-square-foot cathedral. “Santa Cecilia! (Saint Cecilia!),” people yell. “Madre de todas las p*tas! (Mother of all the wh*res!)” It's the same rallying cry heard as Gentili’s family leads her out of the cathedral towards the streets of New York City.

“Cecilia!”

Contact us at letters@time.com.