The Savannah Music Festival celebrates global roots music; those roots lead back to Africa

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In just a few weeks the streets of Savannah will be buzzing with people who have expectations of experiencing another exciting year at the Savannah Music Festival. This annual 17-day festival begins during the last week of March and runs through mid-April. Hundreds of music industry’s finest artists from myriad genres provide jaw-dropping performances that will move audiences to sing, dance and “remember the times.”

This year the festival celebrates its 34th season and is noted as “Georgia’s largest musical arts event and one of the most distinctive cross-genre music festivals in the world.” And, to think, it happens every year right here in beautiful Savannah – the hostess City of the South. Audiences will be able to enjoy a little bit of Blues, a little bit of Jazz, a little bit of funk, rock-n-roll, R & B, big orchestra, symphony and more. Performances will please the palettes of music lovers of almost every genre.

Music is 'cultural universal'

Music is considered “cultural universal,” meaning that it is found in every culture and doesn’t have a definitive starting point.

For the purpose of this column, let’s begin in Africa. Music in Africa can be documented as far back as 6,000-4,000 B.C. in a rock painting of a dance performance attributed to the Saharan period of the Neolithic African hunters. According to Kubik and Robotham (2023, Encyclopedia Britannica), the body movement and movement style depicted in the painting are reminiscent of dance styles still found in many African societies. It is undisputable that many musical genres derived from the contributions of Africans and their descendants throughout the Diaspora – including the distinctly American art forms of Blues, Jazz, Gospel – and, of course, the Negro Spiritual.

Negro Spirituals are folk songs created by enslaved Africans. It is said that the songs created by the enslaved Africans are synonymous with dignity, resolve and occasionally, some joy. Their songs revealed their stories of life, death, faith, hope, survival, and escape from the bonds of slavery.

According to the National Association of Teachers of Singing, Inc. (NATS), the melodies and their stories have been passed down from generation to generation – from plantation fields to praise houses to camp meetings to passages of escape to churches to contemporary concert halls, world stages and recital series. Although born from a very dark period of our nation’s history, these songs ring out a story that continues to be relevant – a story that still needs to be told. The lyrics ring out words of sorrow, hope, survival, and anticipation of better things to come. The stories simultaneously inspire and cause us to pause and reflect. The melodies simultaneously make us mourn, cry, and rejoice.

Hidden meaning of lyrics in Negro Spirituals

Often, the words to Negro Spirituals have dual and/or hidden meaning. Many are sung in a call-and-response form, where a leader’s voice rings out a line and singers follow with a unified refrain. Consider “Wade In The Water.” This Spiritual is believed to be a warning to the enslaved who were escaping to freedom. The lyrics tell them to use the waterways to hide their body scent from the bloodhounds used to locate them.

Another interpretation of the lyrics focuses on spiritual rebirth and redemption through baptism as the enslaved “wade in the water.” For many, their faith in God is what sustained them to survive the horrors of their pain. Additionally, water often was viewed as a source of spiritual power and cleansing. Thus, some believe the line, “See that band all dressed white, God’s gonna trouble the water” speaks to the anticipation of a supernatural intervention and the existence of guardian angels ready to help and shield them.

Another example is “Steal Away to Jesus." No doubt, to the casual observer, this song is about seeking solitude and comfort in Jesus. However, it has been decoded to reveal words encouraging the enslaved to get away to a place where other enslaved persons were gathered for a church service or a planned escape. If the latter, “Jesus” represented the leader of the planned escape.

“Go Down Moses” provides yet another example of the double meaning in the words of many Negro Spirituals. The lyrics focus on Moses confronting Pharoah to demand release of the Israelites from Egyptian bondage. For enslaved Blacks who resisted slavery through escape, the words were a covert call for a leader, like Moses, to lead them out of the evils of slavery. For many, Harriet Tubman, who was nicknamed “Moses” by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, was indeed that leader. True to her nickname, Tubman made about 13 rescue missions resulting in leading no less than 70 people out of slavery.

Another Negro Spiritual associated with Tubman is “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” In her biography of Tubman, Sarah Hopkins Bradford (1886) informs that when an enslaved Black heard this song being sung, he or she knew they had to be ready to escape because a group was getting ready to leave (the band of angels). According to Bradford, the Underground Railroad was the “sweet chariot” that was coming south (swinging low) to take the escapees north to freedom (carry me home).

The double meaning in many Negro Spirituals is simply ingenious. The fact that enslaved Blacks used praise songs to the casual listener that actually provided coded instructions is testament to their significant intelligence. These songs were birthed from Blacks, who were presented to the world as properties to be sold and traded, as being less than human. These songs are reminders that Blacks captured in Africa were mathematicians, scientists, queens, kings, royalty, astronomers, educators – intelligent people who were forced to become enslaved people in the New World.

A Gullah Geechee Negro Spiritual is official state historical song of Georgia

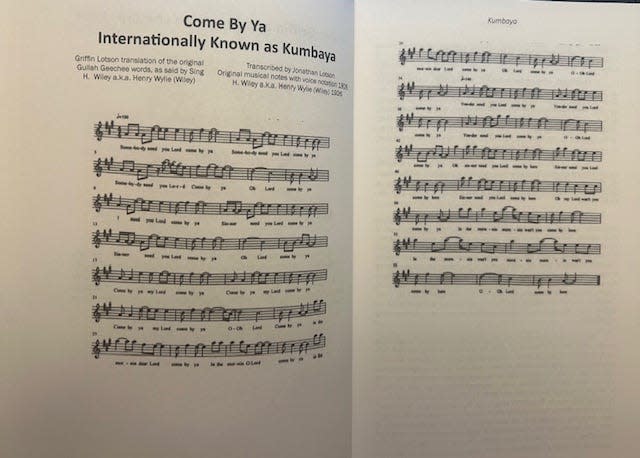

One Negro Spiritual has its birthplace as a recorded song in Darien, Georgia. The song is "Kumbaya," and thanks to Griffin Lotson it is now recognized as the official State Historical Song of Georgia. In his book, Kumbaya (2021), Lotson =explains that “ya” means “here” in Gullah and that “come by ya” is a Gullah Geechee term that has evolved into mainstream American Lexicon. Lotson’s research revealed that Henry Wylie recorded the song in 1926 in his native Gullah Geechee language.

The original words, reprinted with permission, are:

“Somebody need you Lord, come by ya. Somebody need you Lord, come by ya. Oh, Lord, come by ya,

I need you Lord, come by ya

Sinner need you Lord, come by ya. Sinner need you Lord, come by ya, oh Lord, come by ya

Come by ya, my Lord, come by ya. Come by ya my Lord, come by ya. Oh, Lord, come by ya.

In the morn in, dear Lord, come by ya; in the mornin', O, Lord, come by ya,

In the morn in, dear Lord, come by ya, oh, Lord, come by ya,……

Oh, Lord, come by ya.

Yonder need you, Lord, come by ya. Yonder need you, Lord, come by ya. Yonder need you, Lord, come by ya. Oh, Lord, come by ya.

Oh, sinner need you Lord, come by here, Sinner need you Lord, come by here, Sinner need you Lord, Come by here, oh my Lord, won’t you come by Ya,

In the morn in’, morn in’, won’t you come by here, in the morn in, morn in, wany you come by here

Oh, Lord, come by here."

Although birthed out of the experiences of enslaved and freed Blacks, Negro Spirituals are sung and enjoyed by diverse singers and in diverse venues across the world. United Parish, a predominately white church in Brookline, Massachusetts, began celebrating the musical legacy of enslaved and freed Black Americans with their Negro Spiritual Royalties Project, launched in 2021. Through this project, the parish collects an offering to donate to the development of young Black musicians every time they sing Negro Spirituals. This is their way of giving back, of making reparations.

While this month’s column isn’t about making reparations, it is about celebration. This year, as the City of Savannah prepares to host thousands of people who will enjoy the sounds pulsating from the Savannah Music Festival, take time to pause and remember that people throughout the Black Diaspora have contributed significantly to music played in every genre. Take time to honor Blacks who never received credit for the songs they composed. Take time to enjoy the melodies and words that feed souls. Take time to “remember the times.”

Here are links to a few Negro Spirituals: (all under Public Domain)

Swing Low Sweet Chariot: loc.gov/item/jukebox-14854/

Sometimes I feel Like a Motherless Child: loc.gov/item/lomaxbib000555/

Rocky My Soul: loc.gov/item/ihas.200197579

Steal Away: loc.gov/item/jukebox-4649/

Maxine L. Bryant, Ph.D., is a contributing lifestyles columnist. She is an assistant professor, Department of Criminal Justice & Criminology; director, Center for Africana Studies, and director, Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Center at Georgia Southern University, Armstrong Campus. Contact her at 912-478-1248 or email dr.maxinebryant@gmail.com. See more columns by her at SavannahNow.com/lifestyle/.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Savannah columnist shares hidden meaning of Negro Spiritual lyrics