Saudi king's visit to Russia heralds shift in global power structures

Vladimir Putin hopes first official trip by Saudi monarch to Moscow will seal powerful new alliance centred on oil and conflicts in the Gulf states

Russia will host its first visit by a Saudi monarch on Thursday, in an attempt to seal an alliance that would confirm Moscow as a major independent force in the Middle East capable of shaping worldwide oil prices and the outcome of regional conflicts such as those in Syria and Libya.

With diplomatic alliances shifting across the Middle East, Moscow hopes that King Salman’s historic four-day visit will show that Moscow can forge close alliances with all the key Middle East players, including Turkey, Iran and now Saudi.

Only two years ago, the idea of a Saudi monarch visiting Moscow would have seem far-fetched, as Moscow and Riyadh have opposed each other for decades on every major regional conflict, from Afghanistan to the role of the Muslim Brotherhood.

But the two sides have decided to end their animus, and in a round of meetings will sign commercial deals, coordinate on oil prices, and discuss a potential peace settlement in Syria, including the future role of Iran, now that it seems clear that President Bashar-al Assad is not going to be deposed.

As many as 100 Saudi businessmen are accompanying the King to Moscow and a £1bn joint oil investment fund is due to be agreed.

The Saudis, normally heavily dependent on US goodwill and oil consumption , have tended to shy away from an ambitious foreign policy, focussing narrowly on the country’s opposition to Shia Iran. But over the past few years, increasingly wary of American reliability, the Saudis have started to diversify their diplomatic alliances, including building contacts with forces with which it had previously refused to have dealings, such as Shia figures in Iraq.

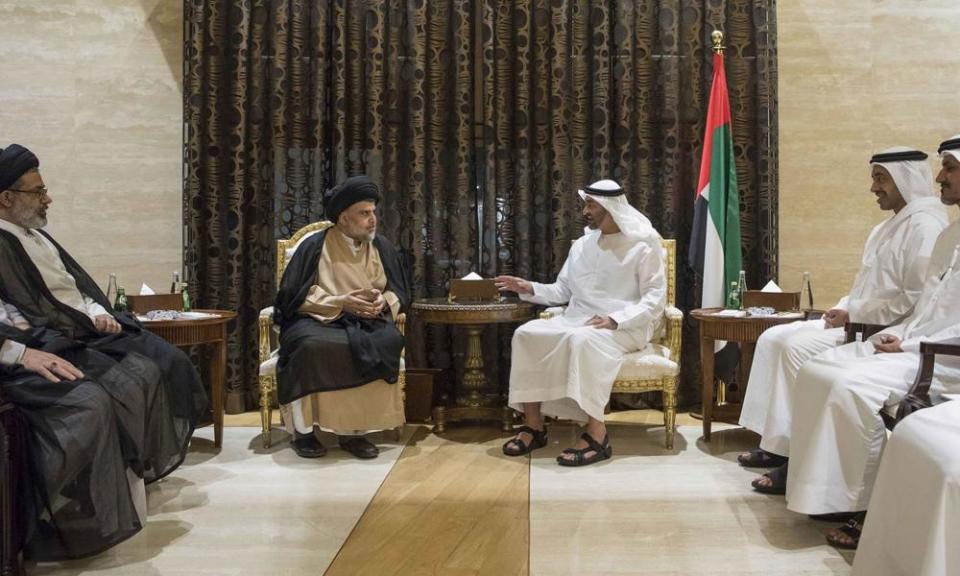

In recent months, Saudi, the region’s Sunni powerhouse, has hosted Muqtada al-Sadr, the influential Shia cleric. Riyadh and Baghdad have also said they will open the Arar border crossing for the first time in 27 years.

Much of the new activism is being driven by the king’s modernising and ambitious son, Crown Prince Mohammed Ibn Salman, the de facto orchestrator of Saudi’s high-risk foreign policy, including the military intervention in Yemen, and the trade boycott of Qatar, its onetime partner in the Gulf Co-operation Council.

The change has partly been forced upon Saudi due to the successful Russian-orchestrated advance by the Assad government in Syria, and the consequent military reverses for the Saudi-backed opposition.

There has been recrimination across the Gulf for the failure of the Syrian opposition and Russia’s success, with some blaming Saudi’s refusal to arm groups linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. Many Saudi commentators have expressed frustration at Donald Trump’s lack of a policy on Syria beyond the defeat of Islamic State.

But Russia’s success means the diplomatic energy in Syria has shifted towards the joint Russian-Turkish-Iranian formation of four de-escalation zones in Syria, a process that Saudi now pragmatically has been forced to support. Saudis are due to stage another meeting of the Syrian opposition in Riyadh in the middle of the month in a bid to unify the Syrian opposition and restructure its political demands.

At the same time, Riyadh, in common with Israel, will raise with Moscow its concern that these zones may guarantee a long-term presence for Iranian and Hezbollah troops inside Syria.

Both Israel and Saudi Arabia fear that with Russian acquiescence, Iran is building a corridor of territorial control through Iraq and Syria to its powerful proxy Hezbollah on Israel’s border in South Lebanon.

Russia is also hoping that today’s round of meetings will confirm closer cooperation between the two giant oil-producing nations, leading to a longer-term agreement to constrain production and prevent a further fall in oil price. Russia is not a member of the Opec oil producers cartel.

But in late 2016, 24 oil-producing countries, including Saudi and Russia, agreed to reduce overall output to around 1.8m barrels per day. The deal has been extended to March 1 2018 and is aimed at reducing the global oil surplus that had led to crude oil falling to a 13-year low of under $30 a barrel last year.

Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, speaking in Moscow ahead of King Salman’s visit, said: “What we’ve done serves the entire global economy well” – remarks that suggest Russia would like the deal to be extended. He added: “We will look at the situation in late March. I think it is possible.” He implied that any renewal would take the deal to the end of 2018.