Saturn's Dazzling Rings Make It 'Rain'

It's raining on Saturn, and the giant planet's amazing rings are apparently the cause, scientists say.

A new study unveiled today has found that erosion from particles making up the icy rings of Saturn are forming rain water that falls on certain parts of the planet.

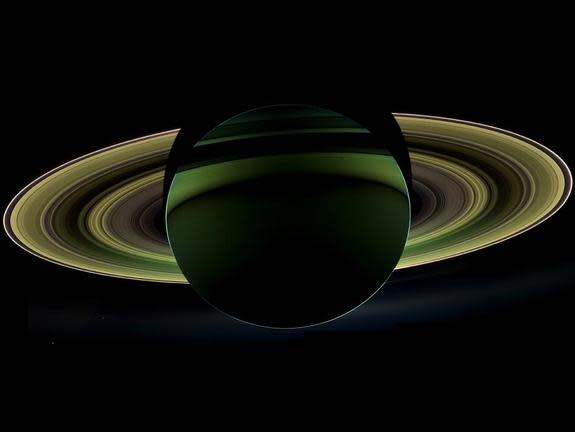

Scientists using the Keck Observatory in Hawaii have found that tiny ice particles that compose the planet's distinctive rings are sometimes eroded away and then deposited in the planet's upper atmosphere. The droplets then create a kind of rain on the planet. [Amazing photos of Saturn's rings]

"We estimate that one Olympic-sized swimming pool of water is falling on Saturn per day," James O'Donoghue, an astronomer at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom and an author of the study, told SPACE.com in an email.

It's raining on Saturn

By using data from the Keck Observatory collected over the course of two hours in 2011, O'Donoghue and his team were able to observe pieces of the ringed planet that have never been mapped in such exquisite detail.

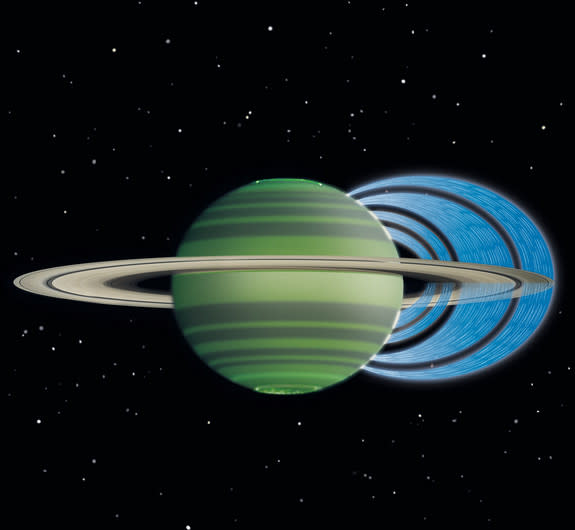

The team found that charged water molecules rain down only on certain parts of the planet, which show up darker in infrared images. O'Donoghue found a connection between those parts of Saturn and the parts of the rings heavy in ice.

"The most surprising element to us was that these dark regions on the planet are found to be linked — via magnetic field lines — to the solid portions of water-ice within Saturn's ring-plane," O'Donoghue said.

The magnetic connection creates a pathway for small ice particles in the rings to slough off into the planet's atmosphere, causing the "ring rain."

Because O’Donoghue and his group located the source of the ring rain, it might now be possible to work backwards to see how those charged water particles became vulnerable to erosion in the first place.

The research is detailed online in the April 10 edition of the journal Nature.

Saturn's ringed past

Most of the mass in Saturn's rings today is separated into "boulders" that are a few centimeters in diameter, but scientists have never pinned down the evolutionary past of the rings. Planetary scientists do know that the rings have not always been so clumped, Jack Connerney, an astrophysicist working with NASA who wasn't involved with the study, told SPACE.com.

"So what you have to do is get your mind around the idea that over millions of years, that boulder has not been a boulder," Connerney, who wrote a commentary on O'Donoghue's study in Nature, added. "Mass is transferred from one boulder to next, and while it's transferred, [the particles are] vulnerable to erosion mechanisms."

This could account for why O'Donoghue and his team saw rainfall on the gas giant.

O’Donoghue's study also could help further explain why each of Saturn's rings is a different density and size. The magnetic field that makes it rain in certain areas of the planet also could control the space and composition of the rings.

"It's quite possible that the rings we see today were shaped — or sculpted — by this process," Connerney added. "So, yes, acting over millions of years this process can remove mass from the ring plane, and who knows — a few tens of millions of years from now it can look quite different."

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.