A salute to Raleigh’s veterans slain overseas, marked on the city’s 100th Memorial Day

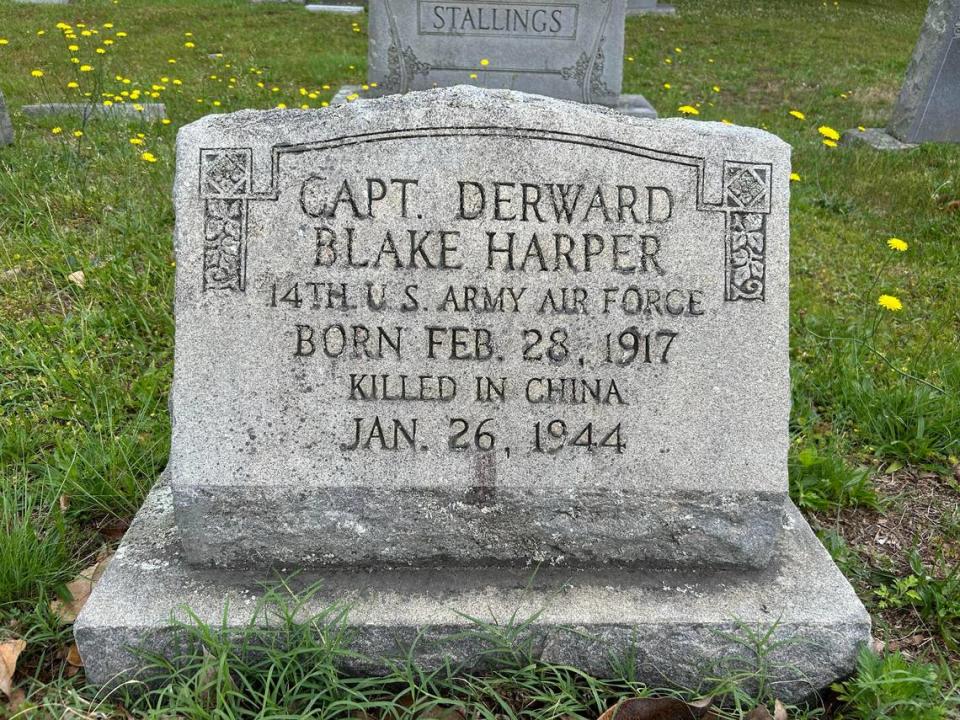

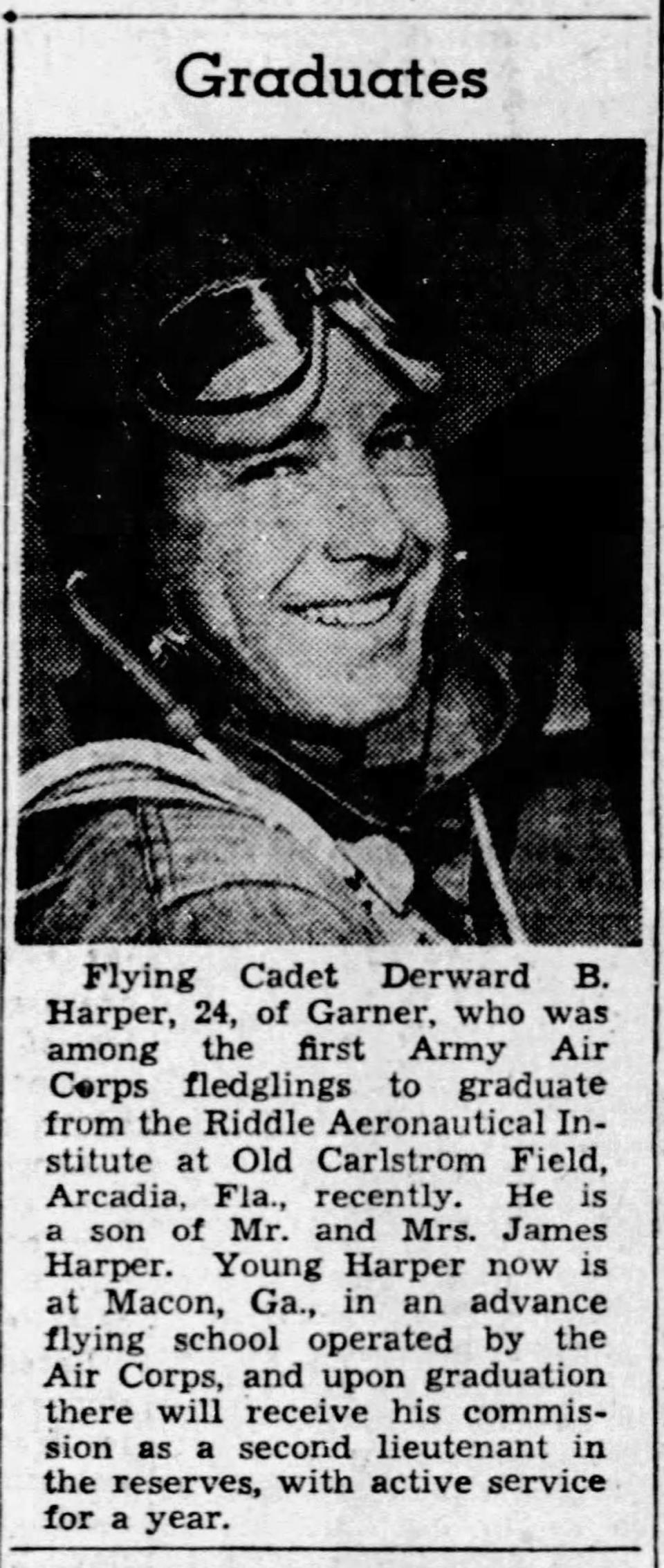

Near the end of World War II, a bomber pilot from Raleigh hit a patch of stormy weather and crashed his B-25 into the side of a Chinese mountain, dying at 26 along with his crew.

For more than a year, Capt. Derward Harper lay under a wooden cross in Yunnan Province — 7,000 miles from home.

Then, once the war had ended, the Army sent Harper’s family a letter: he’d been disinterred and reburied near his base, “with fitting dignity and solemnity.” Two years later, the family got another letter: he’d been moved again — this time to Hawaii.

Finally, after five years and a tall pile of government mail, Harper’s casket reached Raleigh, where his wife had remarried and his mother grown old.

And they held his fourth funeral.

“I don’t know if people can understand this process,” said Robin Simonton, executive director of Oakwood Cemetery, where Harper now rests. “I see loss every day, but I’ve never been here during a war. It’s loss and logistics.”

Raleigh’s 100th Memorial Day

This month marks the 100th anniversary of Raleigh’s first Memorial Day, a ceremony it was slow to embrace. One ugly reality shaped the city’s decision to join the national observance: huge numbers of soldiers getting shipped home from World War I in caskets.

Not only did Raleigh find itself burying men in their 20s, it struggled to retrieve those soldiers from the battlefields in France, blown apart by artillery shells or ravaged by Spanish flu, hastily buried in makeshift graves with their unfortunate comrades.

In their new book “Bringing Them Home,” Simonton and Raleigh historian Bruce Miller trace the path of dozens killed in Gettysburg, in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, along the Hindenburg Line in World War I, in Germany or Japan and all the way to Quan Nam in Vietnam — each of them painstakingly delivered to Oakwood.

In World War I, especially, the process could take a decade and sheaves of paperwork, sometimes delivering the wrong body to the wrong cemetery, sometimes never finding them at all.

“It’s a process that’s seldom understood,” said Miller. “We’ve heard people say, ‘He died in Korea and was buried in Anytown, USA.’ The middle part is gone. It’s lost, and it’s as if it were magic.”

In their book, Simonton and Miller try to both elevate the dead and demystify the words on their memorials: Killed in China; or Died in Rangoon, Burma; or Bon Voyage, Tom.

Here are a few of the stories they found in the world’s archives, charting Raleigh fighters.

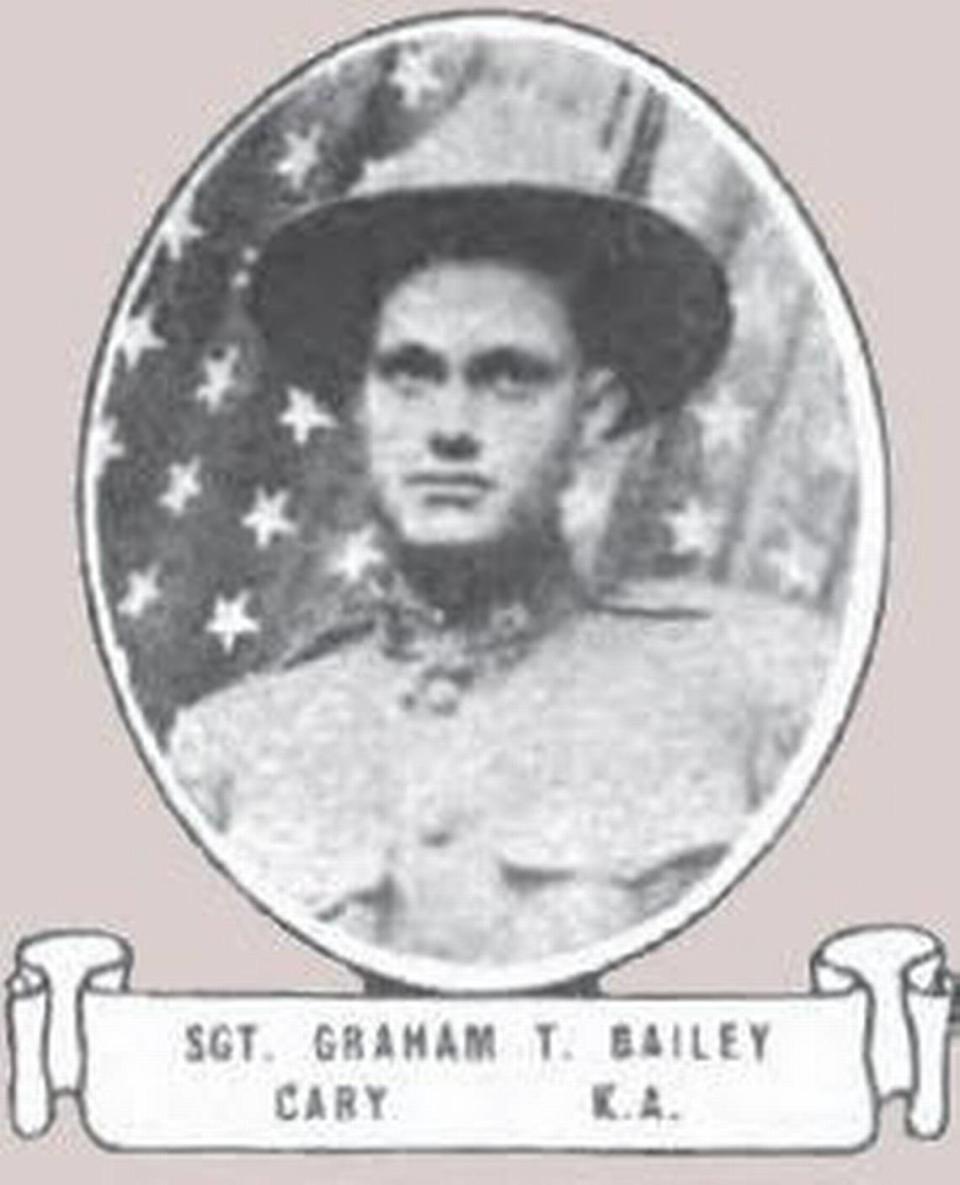

Graham Bailey: Whereabouts unknown

Born into a rough life, Bailey lost his mother as a boy then saw his father declared insane, confined to a mental institution where he died of auto-intoxication. At the time, neither Bailey nor his brother knew their grandparents names.

This string of misfortune led to Bailey joining the NC National Guard, then shipping out to the Western Front in 1918 as an Army corporal. By May of that year, he found himself in no-man’s-land near Ypres in Belgium, joining raids and taking German prisoners.

During one September assault, the deadliest day for North Carolina troops, a single German shell killed four American soldiers, including Bailey. Soon his sister asked for the body, by then buried in a French cemetery, to be shipped back to their home on Harp Street.

But Bailey’s whereabouts, lost in a tangle of paperwork, never surfaced. By 1921, the government learned that the soldier in the grave marked with Bailey’s name was actually Pvt. Martin Taylor. Somebody else wearing Bailey’s dog tags ended up in a third grave nearby.

So the government asked the sister for dental records, and whether her brother carried any scars or fractured bones, none of which she knew for sure. The inquiry continued for eight years and only further described the carnage behind his death.

More than a century later, no one can say where Bailey rests.

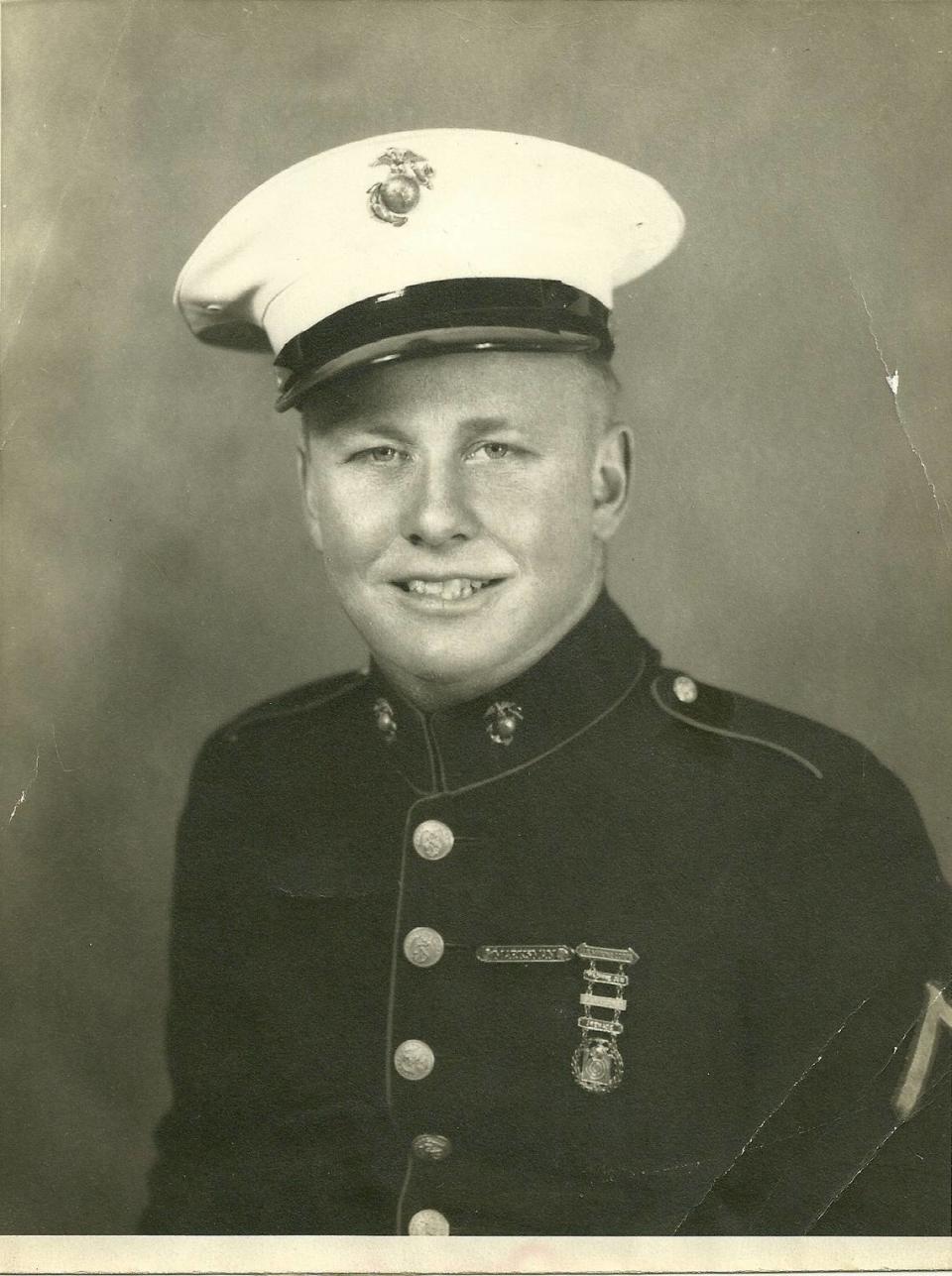

Bobby Crocker: ‘Slight mishap’ turns fatal

On the day Bobby Crocker went to war, he was still only 18, a star fullback at Raleigh High School — a player so dominant that in his final game he ran for two touchdowns and passed in a third.

But the day Crocker left Raleigh — Oct. 2, 1943 — he couldn’t suit up to play. Drafted into the Marines, his train left at halftime.

So he watched his teammates play the game they dedicated to him, then at halftime walked from the field to his train at Seaboard Station. The platform stood so close that fans could watch him all the way.

“If the stocky youngster fights as hard as a Marine as he played football,” The News & Observer raved, “he will continue to make headlines.”

But Crocker never saw action, and he never lived the heroic story his hometown predicted.

On a stopover at Eniwetok atoll in the Pacific, he was cleaning latrines when his supervisor showed off his .45-caliber pistol, which accidentally fired and sent a bullet through Crocker’s chest.

In a letter home, Crocker described his injury as a “slight mishap” and asked if his brother Bill was still fooling with the girls. “I notice in the last picture from him, he was sporting a new zoot suit,” wrote the teen. “Is Betty still as pretty as she was when I left? ... I believe if we can get rid of Germany in the next few months, I will probably be eating turkey with you next Christmas.”

But Crocker would later die from the injury.

It took till 1947 to get him home. He’d been buried twice before.

Memorial Day tours at Oakwood

Oakwood Cemetery will hold Memorial Day tours with a costumed guide and history tent from noon to 3 p.m. on May 27.

Sign up here or at: https://historicoakwoodcemetery.org/event/observe-memorial-day-at-oakwood-family-tours-and-history-tent/

‘Bringing Them Home’ book

These and many dozens of other stories make up “Bringing Them Home,” which can be purchased here or at:

https://historicoakwoodcemetery.org/product/bringing-them-home-raleighs-oakwood-cemetery-and-the-dead-of-americas-wars/