Russian Fireball Fallout: Huge Asteroid Numbers Raise Stakes of Impact Threat

The number of asteroids zooming close to Earth is far greater than previously believed, highlighting the need to ramp up efforts to find and track these potentially dangerous space rocks, experts say.

A new analysis of the Russian meteor explosion that injured more than 1,000 people in the city of Chelyabinsk this past February estimates that similar impacts occur about seven times more often than previously thought.

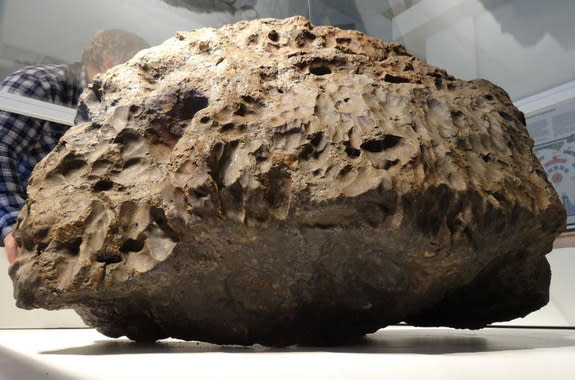

That means there could be more than 20 million near-Earth asteroids roughly 62 feet (19 meters) wide — the size of the Chelyabinsk object — rather than three or four million, scientists say, adding to the Russian meteor explosion's importance as a teachable moment. [See Photos of the Russian Meteor Explosion of Feb. 15]

"It has attracted more attention to the threat," Lindley Johnson, program executive for NASA's Near-Earth Object (NEO) Observations Program, said of the Chelyabinsk event in a teleconference with reporters Wednesday (Nov. 6).

The Russian meteor explosion is a "great advertisement," he added, "that this is really something that we do need to be dealing with, and addressing the improvement in capabilities to detect, track and characterize these objects."

Out of the blue

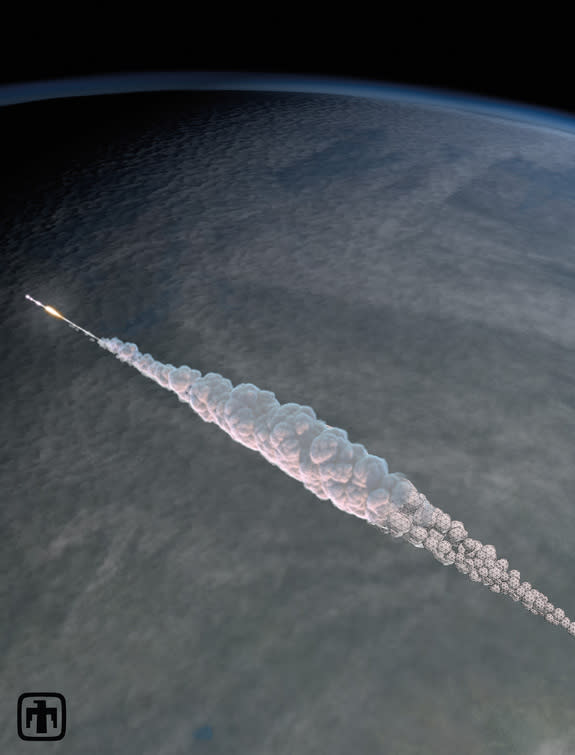

The Russian meteor caught scientists and citizens of Chelyabinsk by surprise, exploding without warning on Feb. 15. The shock wave created by the blast — which was equivalent to about 500 kilotons of TNT — shattered windows throughout the area, sending more than 1,200 people to the hospital. (There were no fatalities.)

It's not terribly surprising that the Chelyabinsk airburst came out of the blue. Scientists have discovered just 10,000 or so near-Earth objects to date, out of a total population that numbers in the millions.

And that population is likely significantly larger than scientists had realized, suggests the new study, which was published Wednesday (Nov. 6) in the journal Nature.

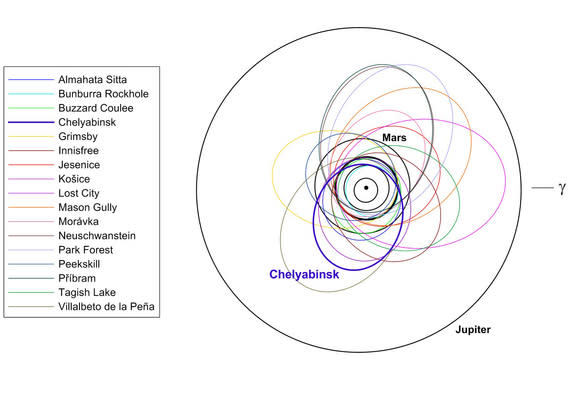

The researchers, led by Peter Brown of the University of Western Ontario in Canada, performed a global survey of recent airbursts packing at least 1 kiloton of energy. They concluded that the number of Chelyabinsk-like events — and, by extension, Chelyabinsk-meteor-size asteroids — appears to be about seven times greater than previously estimated.

While this calculation must be taken with a grain of salt because it's based on a small sample size, it does imply that the number of near-Earth asteroids in the 50- to 100-foot-range (15 to 30 meters) has likely been underestimated in the past, other researchers say.

"I'm uncomfortable to go out on a quote saying that it's actually seven times more at that size range," said Paul Chodas, a research scientist with the NEO Program Office at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., who was not involved in the study. "But I would say it appears to be several times more."

Hunting for asteroids

Astronomers have spotted 95 percent of the 980 near-Earth asteroids at least 0.6 miles (1 km) wide, which might end civilization if they hit us. But if they want to start making real progress in detecting smaller objects like the Chelyabinsk impactor, new tools will likely be needed.

At the top of many scientists' wish list is an infrared space telescope that would hunt for asteroids from inside the orbit of Earth, so it could stare out at our planet's neighborhood without having to fight the glare of the sun.

Such an instrument is already on the drawing board. The nonprofit B612 Foundation, which is dedicated to helping protect Earth against catastrophic asteroid impacts, aims to launch its Sentinel Space Telescope to a Venus-like orbit in 2018. Sentinel should find about 500,000 near-Earth asteroids in less than six years of operation, B612 officials have said.

But defending the planet effectively against space rocks involves more than the launch of one telescope, researchers say. Rather, detecting dangerous asteroids — and eventually deflecting them away from Earth — will require a concerted and sustained international effort, which has likely gotten a boost from the drama in the skies over Chelyabinsk on Feb. 15.

"It's provided, certainly, incentive by not only the U.S. government but nations around the world and the United Nations to improve our coordination of capabilities against this natural threat to the Earth," Johnson said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.