Russia may have just carried out its first direct action against the West

The threat to undersea infrastructure, like every other threat just now, is increasing. Only a few weeks ago the Houthis, so adeptly disrupting commercial shipping in the Bab el Mandeb chokepoint, declared that they were going to add undersea disruption to their playbook. They said they would target the submarine cables that run through the Bab el Mandeb between Asia and Europe.

Many commentators, myself included, thought that despite increasing Russian presence on the ground there – this is known from phone intercepts – the Houthis lacked the expertise to do this in a way that wouldn’t be immediately obvious while it was happening.

Reports yesterday, however, suggest that this judgement may have been premature.

As with all undersea disruption, establishing what has happened is hard. For example, it isn’t clear yet whether it was four separate cables (belonging to AAE-1, Seacom, EIG and TGN) or just one that was severed. Internet monitoring firm NetBlocks confirmed services in Djibouti have been disrupted. Seacom likewise reports ‘cable issues’ but apportions no blame. Flag Telecom founder and telecoms entrepreneur Sunil Tagare said on his social media accounts that it was “confirmed” the cables had been cut – without saying where the confirmation had come from.

It should be noted that just one cable being broken would be quite likely to be just a normal mishap. Cable breaks happen all the time: there are more than a hundred every year.

The other critical information that is missing is ‘where?’. ‘Off the coast of Yemen’ isn’t particularly helpful when it comes to assessing the depth of water and therefore the complexity of the operation and thus who could have done it.

Are the breaks where the cable(s) come up the beach in Djibouti – which would limit any disruption ashore to that area – or was it in 100m of fast-flowing water beneath a (still relatively) busy shipping lane out in the strait? The latter could mean noticeable disruption to all traffic between Asia and Europe, though one should note that there are other cables remaining in the Red Sea and it is also possible to route data south round Africa – or even round the world the other way.

Cutting cables where they come ashore would be trivially easy: it might be done by a ship or a small fishing vessel dragging a hook, and this might appear to be normal activity. The Iranian spy and weapons-shipment vessel MV Behshad has been anchored near Djibouti recently.

Cutting cables without being detected out in the strait would be much more difficult, probably a task for a specially equipped submarine: not a job for the Houthis or even the Iranians, probably.

For now, on this particular incident, we need to be cautious. It’s easy in situations like this for every glitch to start being pinned on it and before you know it, sabotage is ‘confirmed’.

The thing to remember is that whether the Houthis, Iranians or Russians (or a combination thereof) did or didn’t attack cables is less relevant than the fact that they have motive and are accelerating their capabilities in these areas. And who is going to want to take a ship in there to carry out the inspections and then repairs? Not me, unless it’s grey and heavily armed.

Also yesterday, coincidentally, Denmark ended its investigation into the Nord Stream attacks of September 2022. Here gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea were ruptured by a series of blasts resulting in 175,000 tons of methane destined for people’s homes being emitted into the air instead. Minor compared to the 135 million tons a year emitted by the energy sector but it’s still 1.85 million cows’ worth over a year: and Russia’s primary means of exporting gas directly into Western Europe is gone.

And yet despite the disruption and environmental impact, Denmark is officially saying there are ‘insufficient grounds to pursue a criminal case’, following something similar from Sweden earlier this month. Germany remains the only country with an investigation still open and they remain “very interested in getting to the bottom of the blasts” a spokesperson said on Monday.

Needless to say, the lack of finger-pointing has generated a feeding frenzy for conspiracists, taking the silence as a clear sign that it was someone ‘awkward’ like Ukraine who took out Nord Stream. As with the Bab el Mandeb, establishing who did what for certain is not that easy.

The list of countries that might want to remove Nord Stream is long and depending on your preferred theory, it’s easy to provide supporting ‘data’. The US did it because President Biden said he was going to. China did it because they had a ship there that was missing an anchor. Russia did it because satellite pictures show the right sort of ships hovering there at the right time. The UK did it because Russia said so (but they also blame the US and Ukraine depending on the day of the week). Ukraine did it because a yacht was found with traces of explosives on it, and so on.

Motive is one thing: sometimes it helps to look at capability. The Nord Stream 1 blast took place at 95 meters depth, reducing to 78 and 53 for the two Nord stream 2 blasts. So it’s not impossible stuff for either divers or underwater vehicles but given the currents, water temperature and shipping density, not simple either. Importantly the Nord Stream job wasn’t done under intense radar surveillance, meaning that a surface vessel could have been used and a small team well skilled in specialist deep diving techniques – and explosive demolitions – could have done it. Alternatively a reasonably capable remotely-operated vehicle (ROV) could have been used, though this would mean a bigger and better equipped surface support vessel.

So, quite a lot of countries could have done Nord Stream. But the Bab el Mandeb is different. The sea there is crawling with international warships, all scanning their radar with great vigilance, including a US Navy carrier which will be keeping an E-2 Hawkeye radar plane aloft round the clock. Any surface vessel acting suspiciously there would very quickly find helicopters and fast rigid inflatables full of heavily armed, unsympathetic people all over it. So far there has not even been any apparent attempt to lay drifting mines, which would be a lot easier.

So cable cutting in the Bab el Mandeb would really need to be done entirely from underwater – it’s in a different league to Nord Stream.

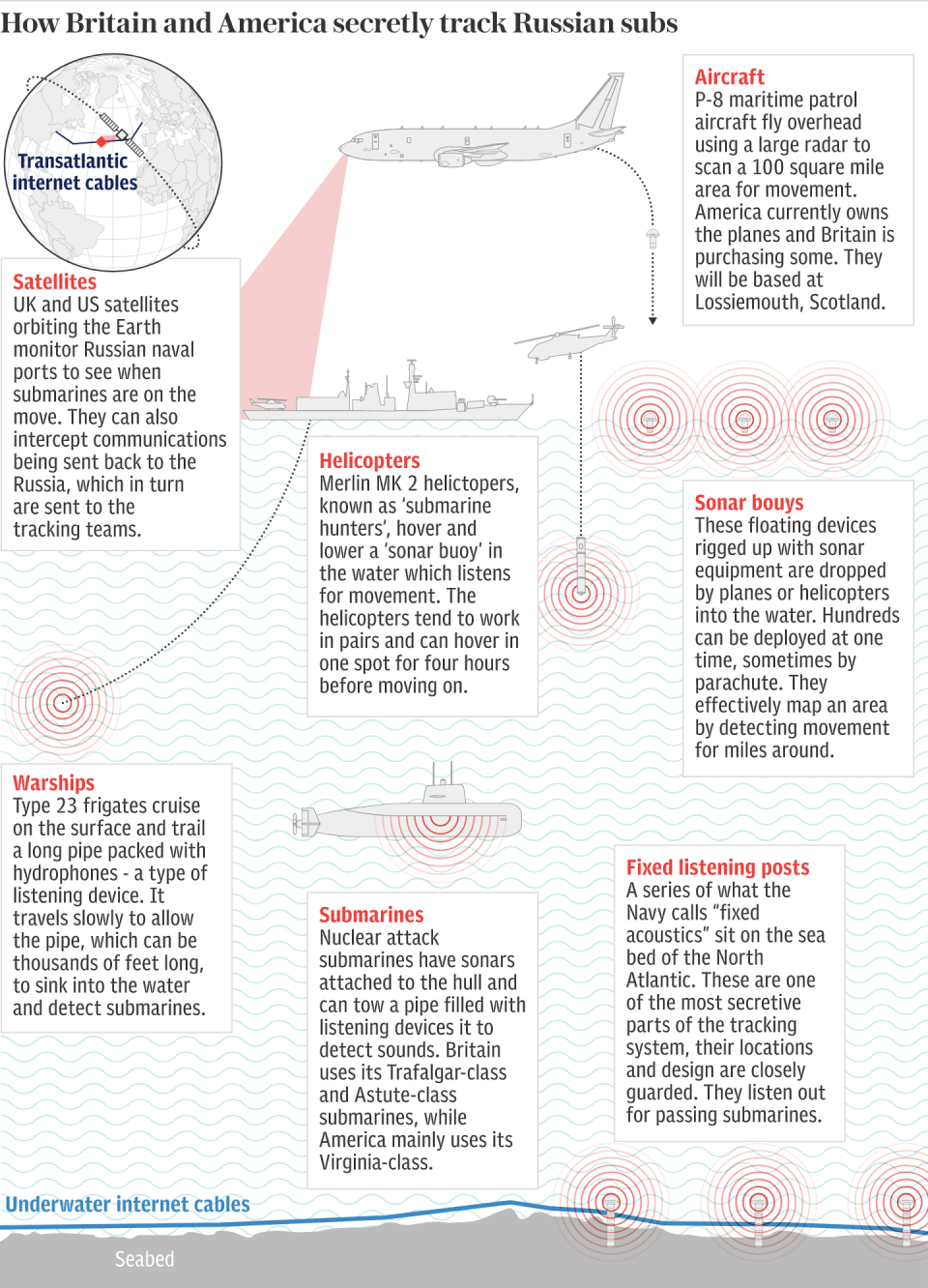

So who can do covert, fully underwater sabotage? Russia can – I spent years of my life in the Greenland-Iceland-UK gap watching them do it. In command of a towed-array sonar frigate, my job was to detect and deter their nuclear powered submarines as they sniffed around the transatlantic communications cables through which trillions of dollars worth of transactions pass every day.

Yes indeed, the Russians could cut cables secretly from underwater. One might speculate that a nuclear submarine mothership would lurk in deeper waters somewhere near and send in an ROV or mini-sub to do the actual work: this would be hard for the warships above to detect. They mostly have sonar and are capable of anti-submarine work, though they’re liable to be focused (much) more on their air and surface pictures at the moment. Alternatively a team might launch ROVs from the Houthi-controlled shore. The Houthis have some ROVs already, but none that look capable of long-range precision work.

I’m not saying the Russians have done this: but someone seems to have done something and not many others could have. This may have been the first direct action by the Russians against the West, as the new Cold War gets hotter.

Many nowadays are calling this type of action ‘greyzone’ activity, the newish term for sub-military adventurism. I would dispute this term when it comes to Russia. For them, it is normal maritime activity. They have a dedicated, highly secret naval sub-sea agency – the Main Directorate of Deep Sea Research, aka GUGI – and specially equipped nuclear-powered submarines dedicated to such tasks. Calling it ‘greyzone’ encourages the wrong mindset when it comes to countering it and being ready to do it ourselves, which should also be considered similarly normal activity for all Western navies.

Some Western navies are better equipped than others. The US Navy, for instance, has the USS Jimmy Carter, a specially modified Seawolf class sub with docking bays and hangars for ROVs and other things – and said to be equipped with dynamic positioning thrusters which let her hover precisely over a point on the sea bed. We in the UK now have Royal Fleet Auxiliary Proteus, the first of our new multi-role ocean surveillance ships: not as covert, but capable nonetheless, certainly when on the defensive.

The lessons from the Bab el Mandeb, Nord Stream and other undersea disruptions are clear. The risk to our Critical Undersea Infrastructure – be that electricity, oil, gas or any of the vital applications of data and communications – is going up. Particularly as an island nation, we in Britain need to be able to deter, detect and if necessary, defeat threats to it. We also need to be able to explore events post-incident (to be first with the truth, a particularly rare commodity in these cases) and be able to repair damage in both peaceful and contested waters.

Just saying ‘the US has got this’ is already looking shaky. We all need to be helping, especially maritime nations like the UK.

Escalating events in the Bab El Mandeb and elsewhere in the Baltic, Red, Black and South China Seas, in the Suez and Panama canals and so on mean that navies and their merchant counterparts are very important things right now.

Critical Undersea Infrastructure is called ‘critical’ for a reason. To protect it, the Treasury needs to get its pre-war chequebook out. Sadly, all I can see now is its pre-election one.

Tom Sharpe is a former Royal Navy officer who commanded four different warships