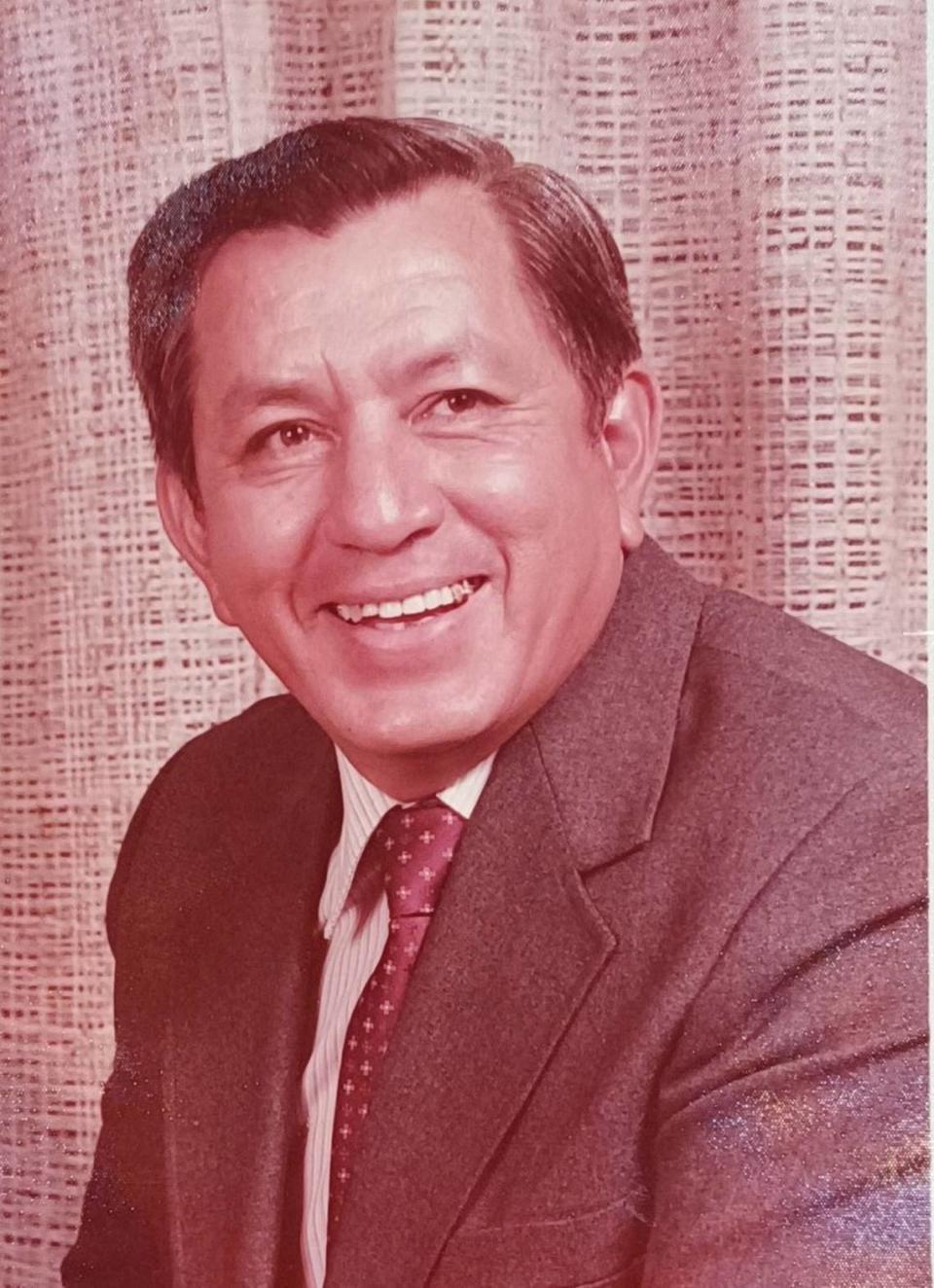

Rufino Mendoza’s fight for equality for Fort Worth Hispanic children: His legacy endures

Texas school districts resisted the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that separate but equal schools were unconstitutional.

Fort Worth ISD was one of the last major Texas school district to integrate in 1963. In 1959, the Fort Worth chapter of the NAACP filed a lawsuit to desegregate. The Mexican American Education Advisory Committee (MAEAC), headed by Rufino Mendoza Sr., followed suit in December 1971 as an intervenor for the district’s discriminatory treatment of Chicano students.

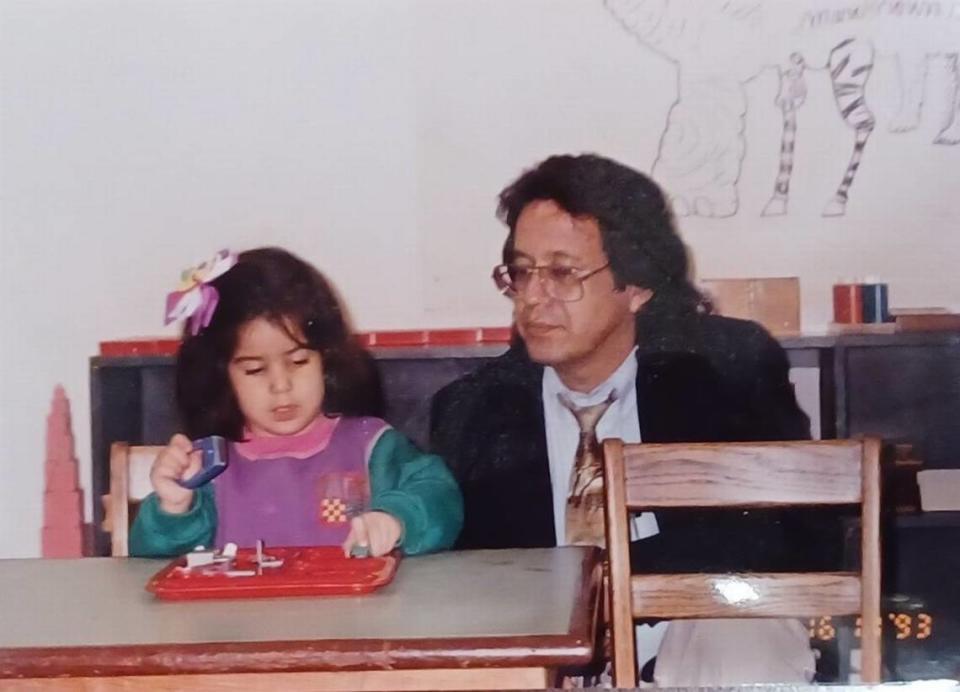

In May 1971, Eddy Herrera led a meeting at All Saints Catholic Church with 60 concerned Chicano parents to discuss their children’s poor educational status. Herrera had taught Rufino Mendoza Jr. at the University of Texas at Arlington and inspired him to become an activist. Father and son engaged Herrera, formed MAEAC, and became president and vice-president, respectively, along with five others. The Mendoza pair proved powerful.

Today's top stories:

→ Baby gorilla born by C-section needs new surrogate mother

→ Student at Eastern Hills Elementary locked in classroom alone, mom says

→ Man nearly decapitated wife, told police she cut herself: affidavit

🚨Get free alerts when news breaks.

Statistics of the time indicated high Chicano dropout rates and low educational performance compared to white students. A 1970 U.S. Civil Right Commission report, “Unfinished Education,” concluded that “Texas provides the worst education for Mexican American students of any state in the Southwest.”

The Texas Education Agency reported in 1985 that incompetent principals and teachers were dumped in four predominately Chicano schools in Fort Worth’s North Side.

Aware of the district’s practice of counting Chicano students as white for integration purposes, the committee immediately demanded they identify them as a separate ethnic group. They also called for the hiring of more Chicano administrators, teachers, counselors and auxiliary staff. Curriculum changes such as the inclusion of Chicano history and heroes were needed.

After six months of unproductive meetings with the superintendent, administrators and school board, the MAEAC retained attorney Ronald Fernandes and sued. Over the years, the MAEAC intervention was called the “Mendoza lawsuit.” L. Clifford Davis, NAACP attorney, welcomed Chicano intervention. Other Black citizens raised concerns the second lawsuit would detract from their initial demands.

Superintendent Julius Truelson said, “We keep telling these people that there aren’t that many qualified Mexican-Americans around for those positions, but they just don’t hear.” Assistant Superintendent Frank Kudlaty warned identifying Chicano people as a distinct ethnic group could destroy the bilingual program.

When Cecil Morgan, the district’s attorney, walked out of negotiations with Davis from Judge Eldon B. Mahon’s court, he told waiting reporters a racial joke that included a slur used against Black people. He bragged he had never been photographed with Davis in his 20 years of litigation and hoped it would never happen in the next 20 years.

MAEAC won in gaining the distinct ethnic status in 1989. In a second lawsuit partnered with the United Hispanic Council over at-large elections, they gained another Chicana representative, Rachel Newman, in 1994.

Mendoza Jr. said the committee contended with Mexican Americans who complained about the legal actions. The Hispanic people who favored status quo claimed the district taught well Chicano students and objected to the troubles MAEAC stirred. Some rejected the Mendozas’ use of the term “Chicano” as an ethnic identifier. Ruben Salazar, a Los Angeles Times reporter, wrote in 1970, “A Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.”

Mendoza Sr. plowed ahead, claiming the first Mexican American trustee at Tarrant County Junior College (as Tarrant County College was formerly called) failed to advocate for hiring and promoting Chicano people. To Mendoza Sr., trustee Pete Zepeda was another safe Mexican American that white people picked to represent the Chicano community.

In a neighborhood meeting with Police Chief Thomas R. Windham, Mendoza Sr. advised him to promote more Chicano employees to policy-making positions. He qualified his remarks stating he sought no personal gains for his three sons who served on the force. Mendoza Jr. was the first native-born Fort Worth Chicano police officer in the city. In 2000, the city appointed Ralph Mendoza as the first Fort Worth Chicano chief of police.

Although Mendoza Sr. had a ninth-grade education, and wife Martina even less, he stressed Chicano people must learn marketable skills to compete successfully. He told Superintendent I. Carl Candoli that he would go to school with his nine children and sit next to them. When the district ignored his daughter Rebecca Mendoza’s teacher application in 1974, Mendoza Sr. announced he knew of a Chicana educator who sought employment. She retired in 2016 after teaching 45 years at Riverside Middle School.

School board member Newman initiated with Mendoza Jr. a North Side petition drive to rename Denver Avenue Elementary for Rufino Mendoza Sr. After receiving over 1,750 signatures, the school board voted 8-1 to change the name in 1998. Jean McClung, the dissenting vote, would later have a middle school named after her.

Mendoza Sr.’s children and grandchildren have a family reunion of sorts when they participate in Rufino Mendoza Elementary School career day. They represent physicians, nurses, engineers, teachers, police officers, attorneys, postal workers and other professions as living testimony to his legacy.

In response to Candoli’s probe of his activism, considering his children were successful, Mendoza Sr. told him not all Chicano children had a father like him. After 30 years working as a postal worker, Mendoza Sr. retired in 1982. At 64, he suffered a heart attack while mowing lawns and died June 25, 1992.

Author Richard J. Gonzales writes and speaks about Fort Worth, national and international Latino history.