Are RPD rules on juvenile use of force working? City blocks records for PAB analysis

As a teenager, Freemonta Strong sat across from city police officers in discussion circles that tried to break down stereotypes and improve police-youth relations in Rochester. Nearly a decade later, in March 2024, Strong found himself revisiting the same conversation about bias and excessive force by police.

An investigation by the Police Accountability Board looked at 318 incidents over a year and a half where Rochester police officers pressed their knees into children’s backs, held juveniles at gunpoint or used other physical techniques to subdue and restrain them.

Black children made up nearly 80% of all recent cases where RPD used force on the city’s young people, according to the report.

Strong was not surprised by the agency’s findings.

This time, though, the conversation ahead of him carried more weight: His 4-year-old son was sitting in the audience of the PAB panel where Strong was speaking as a representative from Teen Empowerment. The boy was mostly oblivious to what was going on around him, tapping through games on a tablet while snacking on gummies shaped like Coke bottles.

But to the adults in the room, he represented the future: How do they create a reality where they can trust he won’t experience police violence?

“We already are fearful of the police,” Strong said. He wants to believe that if his son ever comes face-to-face with an officer, that they would approach the boy with compassion and help — not force. But after the recent PAB report, he feels vulnerable.

PAB: Incomplete RPD records impede investigations, accountability

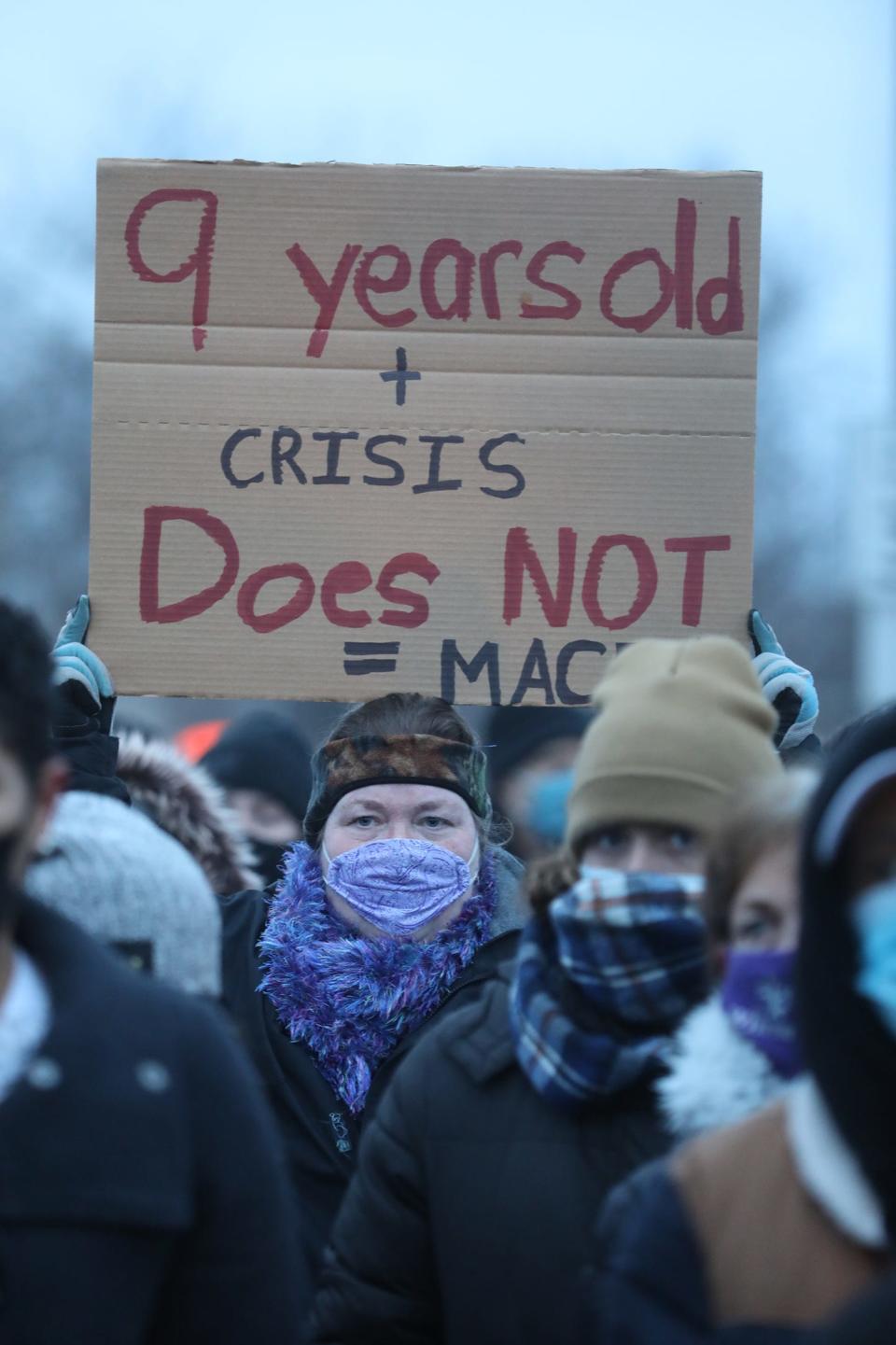

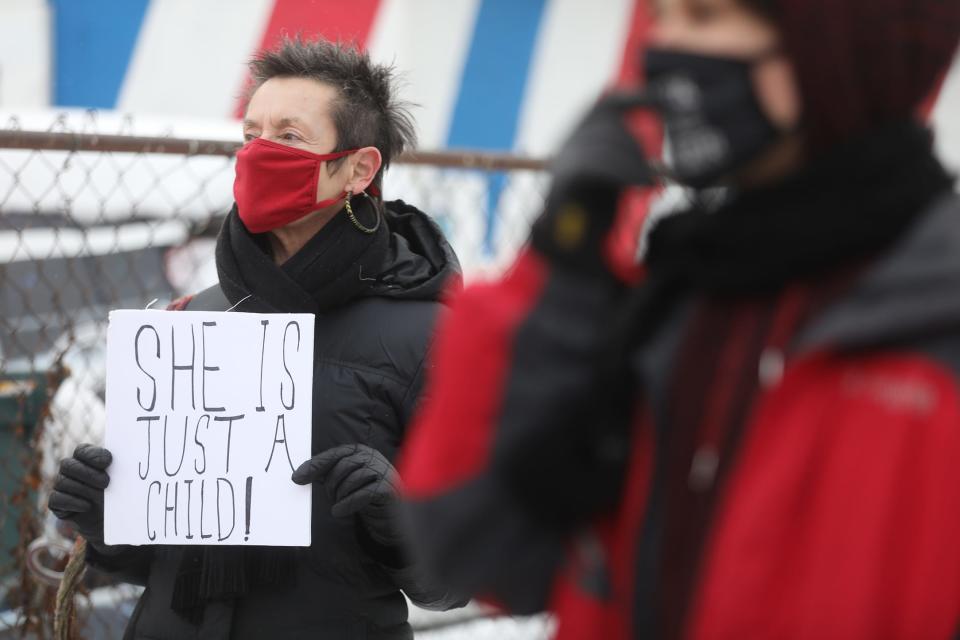

The Rochester Police Department implemented a new juvenile use of force policy in December 2021, months after RPD officers pepper-sprayed a handcuffed 9-year-old girl in the back of a police cruiser.

The incident drew community outrage. The officers involved were not disciplined because, at the time, their actions did not violate RPD policy.

The new policy placed restrictions on how and when officers may use pepper spray, Tasers and impact weapons like batons on juveniles, advised them to use de-escalation tactics in calls involving young people and warned that children might not immediately comply with their commands due to fear or lack of understanding.

RPD Juvenile Use of Force: Police pepper-sprayed a 9-year-old in Rochester in 2021. What happened to investigation?

It’s unclear, however, whether the policy has reduced rates of juvenile use of force in Rochester ― even after the PAB investigation ― because the city has refused to release records needed for a comparative analysis.

'Impractical' to share police records with the public?

PAB investigators said they requested juvenile use of force reports dating back to 2018. The city’s law department denied their request, calling it “impractical and time consuming,” according to the PAB.

Instead, the city said it would only release data from incidents that took place after the policy change ― thereby limiting the scope of the oversight agency’s investigation.

Without the older records, the PAB said it could not evaluate whether the policy “had any meaningful impact.”

A PAB spokesperson said inconsistent access to RPD records remains one of the agency’s biggest challenges.

The PAB has started to issue subpoenas for testimony from RPD officers and said the recent hiring of an in-house attorney will give the agency more teeth in its fight for information.

“These delays and refusals lead to hindered case resolutions, and as we saw in Juvenile Use of Force, the inability to fully analyze data and information related to RPD policies, practices or procedures,” the spokesperson said in an email. “But we are not giving up.”

More on police oversight: Police Accountability Board can't discipline officers, court says. What's next for PAB?

Malik Evans administration hesitant about reports' release

In a statement, city spokesperson Barbara Pierce said the older records were outside of the PAB’s jurisdiction, which she defined as the power to investigate current policies and practices.

“The current use of force policy was enacted in 2021, so any records previous to that do not reflect current policies or practices and are not within the jurisdiction of the PAB,” she said. “PAB’s desire to compare what was happening under former policies versus current policies is comparing apples to oranges.”

Pierce said Mayor Malik Evans had read the report and sees value in analyzing use of force data, but said his administration found several data assumptions and extrapolations in the report that they believe require clarity.

Capt. Greg Bello said the PAB report looked at 318 incidents out of over 300,000 calls for service made to RPD ― or approximately 0.1%.

Bello said RPD consistently reviews its policies and trainings, oftentimes with input from police advisory groups like the U.S. Department of Justice and the Police Executive Research Forum, to “ensure that they reflect or exceed the national standards.”

Since the policy was updated, he said there have been no sustained complaints of force involving juveniles and RPD officers. The police agency, however, does not release information about unsubstantiated complaints or how internal investigators clear those cases.

What did the PAB report find?

The PAB investigation focused on 318 cases of juvenile use of force between December 2021 and May 2023. The report found:

RPD’s use of force records involved youth between ages 2 and 17.

80% of the incidents involved Black children, mostly Black boys.

60% of the incidents took place in the Clinton and Lake patrol sections. Children in the 14621 ZIP code experienced the most incidents, at 20% of the total.

RPD officers pointed handguns and rifles at or near children in 34% of the incidents analyzed.

PAB investigators classified 30% of the incidents as involving a mental health crisis, though it is unclear what criteria the PAB used to determine that.

Read the full report: PAB investigates juvenile use of force

Black youth treated like threatening adults, not children, advocate says

Candice Lucas, the vice president for equity and advocacy at the Urban League of Rochester, said the report demonstrated a common bias playing out in Rochester policing, where Black youth are not treated with the same compassion as other children, but rather seen “as older, as more threatening, as inherently criminal, as dangerous.”

Other panelists and attendees called for RPD to provide more training for officers on how to handle a mental health crisis or approach young people.

Shanterra Mitchum, program director of Teen Empowerment, said the PAB data was important to show behavior that RPD may not have been actively tracking.

“When you are not aware, you do damage,” she said. “You destroy communities. You destroy young people. You destroy everything. It takes a conscious effort to become aware of your implicit bias.”

PAB Town Hall: Juvenile Use of Force https://t.co/H4hdBb52ha

— Rochester Police Accountability Board (@RochesterPAB) March 28, 2024

Several youth organizers from Teen Empowerment were at the event, including panelist Lianny Rodriguez, who said the organization is transformative for young people because it gives them a safe space to grow up.

“The youth that be in the streets, on corners, selling drugs, robbing places, they don’t have anywhere to go,” Rodriguez said. “They don’t got nobody to talk to … and they’re afraid of cops. But if a police officer were to walk up to one of them and actually try to create a bond with them … they’ll see that we’re not bad kids. We’re just people who need help.”

One attendee, Jamella James, turned to those youth and called on them to push for change on an issue that directly impacts them.

“The veil is broken,” James said. “You can actually do something, publish something, say something that’s going to matter, that’s going to last…

She paused and pointed to Strong’s 4-year-old son.

“… so that that young man doesn’t have to sit in (your) chair, talking to these people about the same old thing.”

— Kayla Canne reports on community justice and safety efforts for the Democrat and Chronicle. Follow her on Twitter @kaylacanne and @bykaylacanne on Instagram. Get in touch at kcanne@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: PAB investigation looks at how police treat juveniles in Rochester NY