A Rochester father waits years to find out why his son vanished. What he learns is crushing.

On a frigid day in a conference room at the Public Safety Building, Captain Greg Bello diligently types away at his keyboard. Suddenly, the atmosphere is pierced by the projection of case files on a TV screen. Each file is a person missing in Rochester.

It's a parent's worst nightmare.

Ray Bradley still waits for word of what happened to his adult child, Johnny Bradley. But he wasn't just waiting for Johnny to come home; he had been striving for years and years to get case details from the police department.

When the paltry answers about the police search for his 20-year-old came, they were a bitter shock.

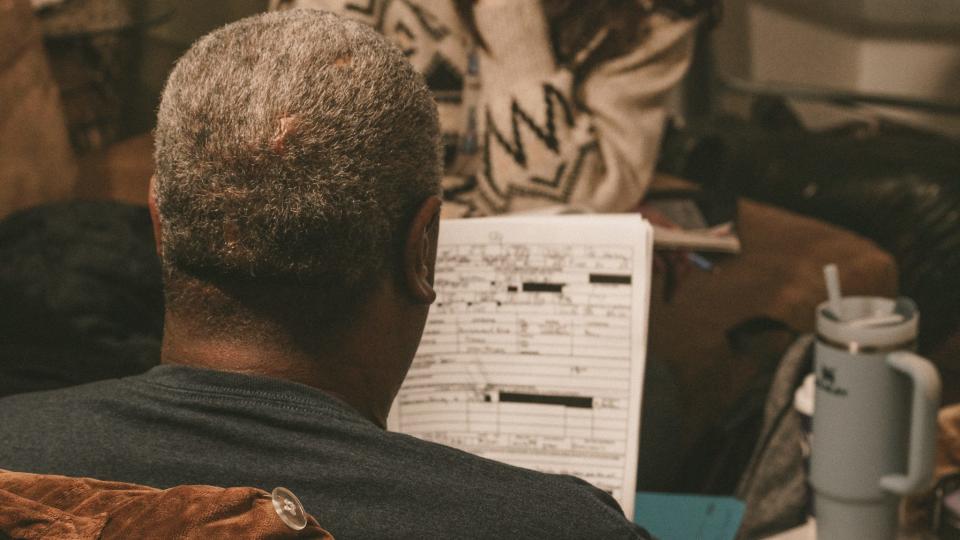

Or was it a surprise? In a way, what he saw in the blue folder containing his son's case file that he opened for the first time at Christmas was something he had expected all along.

Group you don't want to be in: Parents of missing children

At first glance, Ray Bradley is like any other 57-year-old man. He works as a medical transporter every morning, driving clients to and from their doctor's appointments.

He spends most of his weekends with his grandkids, though his five grandsons are on time-out from Grandpa's house until February due to the mass destruction of juice boxes and candy they left in his living room the last time they slept over.

But for the past 19 years, Bradley has been carrying the weight of loss. A dark cloud of grief and frustration follows him everywhere but isn't always visible to the naked eye.

He doesn't celebrate holidays or birthdays. Most nights, he's alone in his living room, watching television until the next day.

The anguish he felt was shared only by the members of a small yet expanding community — a group no parent desires to be a part of: parents of missing children.

Since Johnny's disappearance in 2005, Bradley hasn't been able to shake the feeling that the police department wasn't thoroughly investigating his son's case.

The nine pieces of paper within the blue folder confirmed his worst fears, in his view.

Two of the nine pages were from 2005; the rest were all from 2012. Now he's left to wonder, was anything done between 2005 and 2012? And has anything been done since then?

"What are they doing to me and my family," Ray Bradley says after pounding his fist on the table. "This playing field ain't fair. I'm just over it."

In Bradley's eyes, the lack of information within this folder was evidence that his son's case had fallen through the cracks.

Is anyone looking for Johnny?

How do police investigate missing people?

Bradley's doubts about RPD's investigation into his son's case began the day they reported him missing. He remembers the struggle his family experienced trying to get the officers to take their concerns seriously.

Rochester Police Department says they investigate every missing person case to the best of their ability. Investigator Randy Benjamin says he is actively working on Johnny's case.

To Ray Bradley, it felt like they decided Johnny left on his own before they even got to his house to take the initial report.

And he's not alone in that feeling.

USA TODAY reviewed policy manuals from 55 law enforcement agencies for their national investigation into disparities in missing children's cases. Over 40% of those manuals permit police to allocate less effort to locate runaways than other missing children.

Read More: 'Missing the Missing' offers support, advocacy for families of missing individuals in Rochester

The data supports a pattern where Black children in America are often categorized as runaways rather than missing, leading to disparities in investigative resources. Even though Johnny was over 18, he had a disability and there was tension between the family and police on whether he left of his own accord.

"He's a 20-year-old male; he can leave if he wants to," Ray Bradley recalls police telling him during their initial meeting.

May 3 will mark 19 years since Johnny's disappearance. Throughout this time, Bradley says the police were adamant that they were doing everything they could to locate Johnny — but were they?

Looking at this short stack of records, Bradley couldn't help but think about what was missing.

Where were the reports about the car Johnny was driving that was found abandoned in a parking lot shortly after his disappearance?

Or the ones about his debit card that someone tried to use to rent a car and buy McDonalds in Miami?

Bradley has spent almost two decades navigating the struggles of having a missing child. Now, he was faced with a different type of beast: the realization that those who were supposed to protect and help find his son seemingly didn't.

Go Deeper: What happens when a child disappears in America?

Missing person's investigations: What did Johnny's look like?

Retired RPD officer Kenneth Coniglio was the initial investigator assigned to Johnny's case. An Investigation Action Report dated Aug. 10, 2005, says Coniglio was canceling the missing persons report as Johnny was reportedly seen by family.

Investigator Randy Benjamin then took over Johnny's case in 2012 as a favor for a friend. Benjamin said he believes Ray called RPD sometime after the case was closed in 2005 to report that he still had not seen Johnny, but he is unsure when the case was officially reopened.

At the Public Safety Building this year, Benjamin, Bello and civilian employee Laurie Van Brederode assured the Democrat & Chronicle they are still actively investigating Johnny's disappearance.

They said they understand families in these situations want answers and, at times, may feel left in the dark but explained that it's vital to withhold certain information about their investigations to protect the integrity of the case.

The lack of resources and staffing can also play a role in this tricky relationship between families of missing children and the police department.

Though RPD has a missing person unit, officers must be assigned explicitly to only investigate these cases.

According to section 6 of RPD's General Order on missing person investigations, cases with extenuating circumstances are immediately followed up by the patrol section of occurrence and then assumed by the Central Investigation Section. Non-extenuating missing person cases are routinely followed up by the patrol section of occurrence after 10 days and then considered by CIS after 30 days.

These CIS investigators often work on multiple cases, making it challenging to stay in constant communication with all the families and victims.

Benjamin admitted there has been inconsistent communication with Bradley throughout the years. He said he understood Bradley's frustration but reaffirmed that police are on the hunt for his son.

Benjamin ended the conversation by offering that though he cannot share every update in Johnny's investigation, the father is welcome to call him anytime.

"Why this case?" the investigator asked Democrat and Chronicle reporters, referring to the newspaper's interest.

For 19 years, Ray Bradley has been asking "why not," regarding this question. He questions why the media has to bring attention for the police to do their job.

This blue folder that Ray Bradley hoped would answer some of his questions only furthered his confusion and frustration. He sat in a state of shock, trying to take it all in. The only thing clear to him at that moment was that he would never stop advocating for Johnny.

"I'm the only voice he has now."

— Robert Bell is a multimedia journalist and reporter at The Democrat & Chronicle. He was born in Rochester, grew up in Philadelphia and studied film in Los Angeles. Follow him at @byrobbell on X and @byrobbell on IG. Contact him at rlbell@gannett.com.

— Madison Scott is a recent college graduate who is an intern with the Democrat and Chronicle. She has an interest in how the system helps or doesn't help families with missing loved ones. She can be reached at MDScott@gannett.com. Tell her if you have a good history book recommendation, especially about the Rochester region.

This article originally appeared on Rochester Democrat and Chronicle: Johnny Bradley disappeared 19 years ago: The case devastates his dad