The Road To Union: The coming of America’s second Constitution

This is the third of three articles dealing with America’s forgotten first constitution: the Articles of Confederation. In this article, Donald Applestein looks at some of the challenges that arose under the Articles that eventually led to the calling of the Constitution Convention.

Click here to read part one and part two of the series.

The traditional, political view of events that led to the calling of the 1787 Constitution Convention in Philadelphia was the alleged defects in the Articles of Confederation. Those were principally in the areas of inability to tax, control and regulate commerce and trade, and the lack of flexibility.

TAXATION

Under the Articles, the Congress had no power tax. It could impose tariffs and duties, but not direct taxes. As a result, Congress was left to make “requests” of the states to send revenue. As would be expected, this system did not produce the revenues needed to finance the War and other costs of government.

Not only were receipts below what was requested, but they were not received in a timely or consistent fashion. This situation precipitated the necessity of seeking foreign loans, primarily from France and the Netherlands. The circumstances surrounding these loans were further exacerbated by the country’s inability to repay them as expected. Following the War, this problem persisted with the continuing for revenues.

All of this had a negative impact on the country’s credit and standing in the community of nations. The repayment problems of Congress spilled over into the private sector, adversely affecting the development of manufacturing, and domestic and international trade.

COMMERCE AND TRADE

Foreign merchants were unwilling to extent credit to United States merchants and manufacturers because of the government’s inability to repay its loans. They said, “if your government does not repay its loans, why should I expect you to repay yours. We won’t do business with you.”

Domestically, individual states imposed tariffs and duties on interstate trade, which hampered development of our domestic economy. Congress was powerless to intercede. Promotion of the domestic economy became extremely difficult, if not impossible. Indeed, many of the Founding Fathers, including George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, were frustrated with interstate commerce.

LACK OF FLEXIBILITY

In order to amend the Articles, all 13 states had to agree to changes. This proved to be a near impossibility. (Imagine requiring unanimity of the current Congress!) Each state wanted to protect its interests above all else, and therefore amending the Articles proved to be impossible. This forced the conclusion that a fundamental change was required, if not a total overhaul of the Articles.

It was these concerns that led to a meeting between delegates from Maryland and Virginia to discuss their common water border. Initially meeting in Alexandria, Virginia, Washington invited the delegates to his home at Mount Vernon, and they began meeting on March 25, 1785.

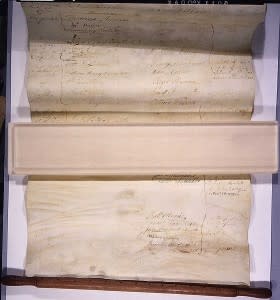

They met to discuss issues of navigation on the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay, fishing rights, and the development of commerce in general. The conference proved successful and produced the Mount Vernon Compact. Under the Compact, which was approved by both legislatures, the Potomac was under Maryland’s sole jurisdiction but was declared a common waterway for use by Virginia. The two states also agreed to share expenses associated with navigation aids, reciprocal fishing rights, and mutual defense. Delaware and Pennsylvania were invited to join the Compact.

In January 1786, with Maryland’s support, Virginia invited all states to a meeting in Annapolis in September to discuss commercial issues and for the reduction of the trade barriers that had developed between the states. Delegates from six states – New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia – met from September 11 to September 14 to discuss reduction of trade barriers. New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and North Carolina appointed delegates, but they did not arrive in time to take part.

The upshot of the “Annapolis Convention” (officially, the “Meeting of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government”) was a report to Congress and the states calling for a constitutional convention in Philadelphia the following May. The report called on all states to attend, and urged that delegates be given authority to examine problems broader than just commerce.

Initially, there was a lack interest among the states to attend, until Washington announced his intention to attend the upcoming convention. With his announcement and the experience of Shays’ Rebellion, there was a distinct change in thinking that the convention was going to be serious. Now, the country was on its way to Philadelphia and its second Constitution.

Donald Applestein is a retired attorney and an experience guide in the National Constitution Center’s Public Programs Department.

More Constitution Daily Historical Stories

Ten fascinating facts on the 70th anniversary of D-Day

10 fascinating birthday facts about President John F. Kennedy