A New Road Threatens to Displace a ‘Safe Haven’ for New Orleans’ Black Youth

NEW ORLEANS — As the youth group sat in its warm-up circle, Kennedy Turner, half-jokingly, scoffed at his peers. “Why didn’t y’all react to my prom photos in the group chat?”

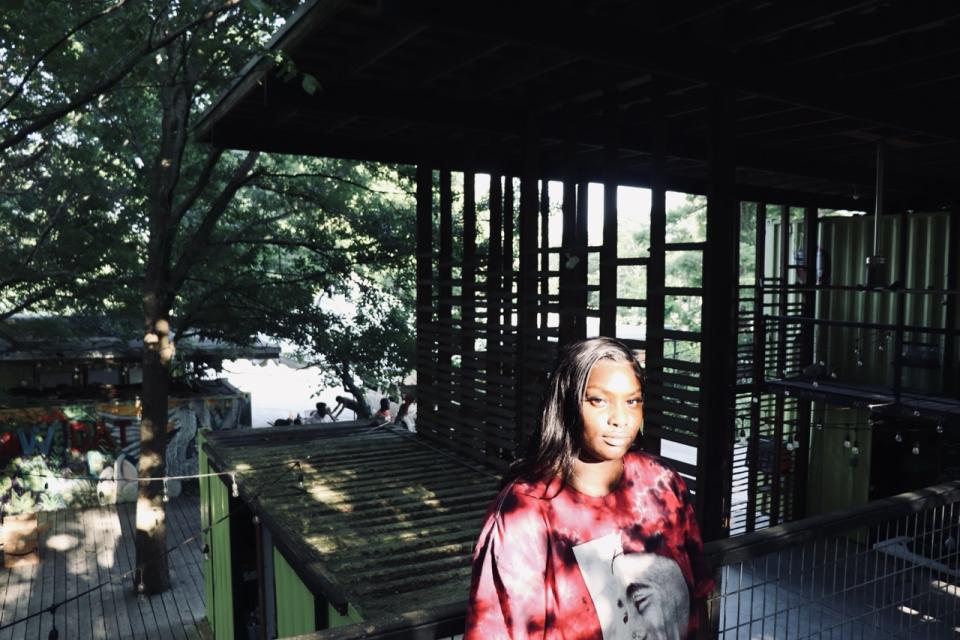

Quickly, Cionne Chase, 19, jumped in to explain that she did, in fact, react to the photos and most definitely did not deserve to be chastised like everyone else. While the conversation fizzled and shifted to other pressing matters like their weekend plans, at its core, it represented something that Turner and hundreds of Black children have come to expect from Grow Dat Youth Farm over the last 13 years: support and consistency.

By most accounts, it is the only youth farm primarily serving people of color in Louisiana, the nation’s second-Blackest state. In the years following a Hurricane Katrina-induced mass exodus of people and resources from New Orleans, it has served as a “safe haven” for Black youth.

Yet, a plan to run a road straight through the 7-acre farm is at the center of a $200 million proposal to revitalize New Orleans’ largest park, where Grow Dat is located.

In a city that has lost one-third of its Black population since 2000 due to the effects of gentrification, the potential displacement of Grow Dat underscores a growing national trend in Black communities.

While gentrification leads to an influx of resources in communities, studies show that it does not trickle down into opportunities for the school-age children originally calling these neighborhoods home. In the aftermath, it can also lead to children from low-income households being shortchanged in the workforce.

As national youth unemployment reaches its lowest levels in two decades, youth subminimum-wage laws have flourished, allowing employers to pay youth less than adults in the same jobs. In Louisiana, lawmakers have even attempted to repeal a law that required youth workers to receive mandatory lunch breaks.

Chase, who has already worked two other jobs before being employed by Grow Dat, says this is the first time she’s been treated like a “human” by an employer: “They actually show that they care about you, and they actually pull you to the side to make sure that you’re OK, that you’re not just overworking yourself.”

The potential displacement of the farm is an example of how local leaders can stunt the ambitions of Black youth when envisioning what they want their neighborhoods to look like and who their neighborhoods can truly serve, explained Jonshell Johnson-Whitten, a farmer and education coordinator at Grow Dat.

According to an analysis by the nonprofit education group Afterschool Alliance, the number of Black children participating in after-school and extracurricular programs has declined by nearly 40% nationwide since 2014. A lot of it has to do with a lack of programs like Grow Dat. Afterschool Alliance found that more than half of Black children who are not enrolled in an after-school program would be in one if one were available.

“Our goal is to have young people leaving this space feeling powerful, feeling like leaders, feeling like they can see an issue and solve it,” she said. “We are trying to build alternatives so folks living in New Orleans can thrive, and it’s harmful for the young people to see that the leaders of today don’t value them.”

Fighting for their “second home”

When entering the green cocoon that is Grow Dat, the outside world “sick” with violence disappears, Chase said. Louisiana has the country’s worst gun death rate for children, and according to a 2021 study, it has the nation’s most “at-risk” youth for economic insecurity, poor educational outcomes, and food access.

Grow Dat has shown Chase that “we can make this world, this planet, into something so much more.”

“If this space didn’t exist, I wouldn’t have learned to move through with this much hope, compassion, and empathy,” said Chase, a self-described “Katrina baby.” She was born the same year the storm ripped through her hometown. After her experiences at Grow Dat, she hopes to become a professional chef and to own a sustainable creole and country food restaurant.

In the weeks since the redevelopment proposal reached the public, hundreds of supporters of the youth farm have mobilized and flooded planning meetings, causing the City Park Conservancy, the organization in charge of the park’s redevelopment, to extend its planning process. Still, the conservancy has said it does not plan to re-offer the farm a new lease once its current one expires in 2027, despite its role in improving food access and youth employment for the city’s Black youth.

According to reporting by local New Orleans outlet Verite News, Grow Dat owes $250,000 in back rent. Grow Dat says it has never received formal communication about overdue rent.

Turner, who will be attending Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge this upcoming fall, likens the situation to the disruption of life that Louisianans are far too familiar with: hurricane destruction. “This is my second home,” he said, and it saddens him to think that he could return from college and it won’t be there anymore. “It’s like you evacuate from your house, and then you come back to see that it isn’t there anymore.”

Since its creation, more than 600 teens have participated and been employed by the farm, which has grown approximately 450,000 pounds of produce for sale and donation across the city.

In addition, the program has filled an educational gap in the city, where 20% of Black adults don’t have a high school diploma compared to 3% of white adults. Regular programming revolves around the history of the land, which is the site of a former slaveholding plantation. (City Park remained segregated until 1958.)

Lessons also often focus on climate change and environmental justice. The programming offers young people the tools to “work with the land and water instead of against it” in the state most impacted by climate threats, explained Johnson-Whitten, a native of New Orleans’ infamously often flooded Lower Ninth Ward.

She does not lose sight of the irony of running a flood-prone road through a green space: “If the climate crisis is here, and everyone says it is here, why are we working against it?” Johnson-Whitten also pointed out that a major highway, Interstate 610, runs along the farm already.

In a statement, Cara Lambright, the CEO of City Park Conservancy, said that while the group is not committing to saving Grow Dat during the redevelopment process, they will spend more time working on ideas to prevent flooding by improving stormwater storage. The new paved road is part of a larger plan to establish easy vehicle, pedestrian, and biking access throughout the 1,300-acre park.

The situation speaks to the value of not only Black youth, but also larger conversations around gentrification, who gets access to nature, and the nation’s goals around constructing the next century’s infrastructure with climate threats in mind. The improvements made to the park are undergirded by attempts to make it more tourist-friendly. (Of the nation’s largest cities, New Orleans is the fifth-most gentrified, according to a study published in 2020.)

“It is showing young people who is really cared about, and it looks like it is not them,” said Johnson-Whitten.

Another shot

Kameron Benoit-Gordon, 20, is candid about how the coronavirus pandemic disrupted his life and how online schooling and a lack of community ultimately led him to drop out of high school. But a job fair in 2022 gave him another shot.

Since coming across Grow Dat at the fair, he’s worked his way through two programs at the farm, hoping to go through a third this summer after he graduates from high school. He returned to school at the same time he started working for Grow Dat. He attributes Grow Dat experiences, like a trip to the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama, as helping to shape his future goals of entering the medical field to improve equitable health practices in the South.

A child of New Orleans, only ever spending time somewhere else as an infant after Katrina pushed his family to Baton Rouge, Benoit-Gordon is also a child of Creole and Southern food. Which means, as he puts it, a lot of fried chicken and fries. But by being involved in cultivating produce, his eyes have been opened to new cuisines. He says the first time a soup that wasn’t gumbo ever touched his lips was here at the farm, as was the first time he ever tasted leafy greens like chard and kale.

One out of three Black children in the U.S. don’t have reliable access to fresh food.

Johnson-Whitten said these kinds of experiences are what make the land special, but they also explain why those in power may not see them as important as the youth.

“People like me who have experienced food apartheid, and who, still today, experiences food insecurity, understand how much it means to see food on the land and see it be fresh and local and nutritious and accessible – and free,” she said, “but If you can access food whenever and however you want with an endless amount of money, then it doesn’t really matter.”

The post A New Road Threatens to Displace a ‘Safe Haven’ for New Orleans’ Black Youth appeared first on Capital B News.