Risky business

Death was not part of the plan.

When NBC began its coverage of the 134th Kentucky Derby, it unfolded as if the network and horse racing were trying to redefine the sport before the horses even reached the track. Hugh Hefner and three Playboy bunnies paraded down the red carpet outside Churchill Downs.

Horse racing is sexy!

Heidi Montag from the MTV's reality show "The Hills" sashayed down the same red carpet.

Horse racing is hip!

The nattily dressed sipped mint juleps from their luxury suites on Millionaire's Row.

Horse racing is chic!

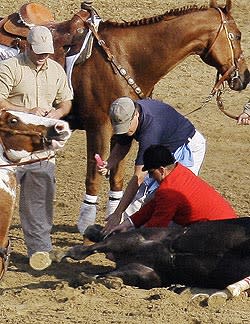

Eight Belles is examined on the track after breaking both front ankles following a second-place finish in the Kentucky Derby.

(AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Then, at the conclusion of what's billed as the most exciting two minutes in sport, tragedy ruined the script – and threatened to further damage a sport clinging to relevancy. Eight Belles, the filly that finished second to Big Brown, broke down 25 yards after the finish line. Her front ankles snapped. She writhed on the dirt. Then she went still.

The track veterinarian had administered a lethal injection.

Public outrage erupted, for just two years ago Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro broke down at the Preakness Stakes and months-long efforts to save him failed. Racing officials explained Eight Belles had no chance to survive. They expressed grave concern for the filly. But as the Preakness Stakes looms on Saturday, racing officials are just as concerned about the health of a sport, which has struggled to cultivate new fans, lost a significant share of the gambling dollar and now finds itself embroiled in controversy.

More than 100,000 fans are expected to squeeze inside Pimlico Race Course for the second leg of the Triple Crown. PETA will be there, too – in full force.

The death of Eight Belles could overshadow a feat many racing officials thought would reinvigorate the sport. Big Brown, the strapping Bay that won the Kentucky Derby in convincing fashion, has stirred hopes of those eagerly awaiting the first horse to sweep the Derby, the Preakness and the Belmont since Affirmed in 1978.

"We're putting on the gas and the brakes at the same time," said Alex Waldrop, president of the National Thoroughbred Racing Association (NTRA). "… We want people to watch Big Brown. But obviously we're concerned about the impact (of Eight Belles)."

PETA, which has never set up a formal protest for one of the Triple Crown races, said it received twice as many e-mails and phone calls over Eight Belles than that poured in after NFL star Michael Vick was tied to the drowning and electrocution of dogs.

"We've had about double the number of visitors to our website since we began putting information about Eight Belles and the racing industry, which caught us off guard," said Kathy Guillermo, a former horse racing aficionado who is PETA's point person for issues concerning the sport. "There is an enormous interest in what's happening now."

Waldorp

Racing officials might find it hard to dismiss PETA's claims or to characterize the outcry as hysteria from people who know nothing about the sport. Two days after Eight Belles was killed, Waldrop, who as president of the NTRA is one of the leading figures in thoroughbred racing, posted on the association's website a blog entitled "Safety First." The item generated almost 800 responses, many calling on the industry to address safety and welfare concerns, compared to the five comments generated by Waldrop's pre-race blog entitled "Derby Fever."

"Completely overwhelmed," he said of the response to his blog.

The use of synthetic turf, restrictions on permissible medication, steroids testing and breeding changes that would strengthen the brittle legs of thoroughbreds are among changes being discussed. But racing also has tried to manage a public backlash for which some had prepared.

ANTICIPATING DISASTER

From a symposium held after after Barbaro broke down at the 2006 Preakness, the attempt to frame a catastrophic injury in more palatable terms comes through in the transcript.

"There's one thing a publicist ought to send e-mails, memos to everybody involved at the various racetracks," Randy Moss, a racing analyst for ABC and ESPN, said during the symposium. "Strike the following words from your vocabulary forever: 'It's all part of the game.'

Go For Wand and her jockey Randy Romero, hit the dirt as they fall during the final stretch of the Breeders Cup Distaff at Belmont Park in New York on Oct. 27, 1990.

(AP Photo/Mike Albans)

"That, as true as it may be, when someone in a position of authority goes on television and says that after an accident like Barbaro or Pine Island (a horse that was euthanized after it broke down during a high-profile race in 2006), it's one of the worst things anyone can say to the average viewer who is watching. It conveys a sense of almost apathy to the whole situation."

During that same symposium, Moss addressed TV coverage of a catastrophic injury on the track.

"I think if there's one moment NBC could go back and change in their history, in covering horse racing, it would be the Go For Wand situation in 1990 where there was incessant replays of Go For Wand going down in the stretch," he said. "That sort of become poster child of how not to handle a situation like that.

"The way we felt about it, the one graphic shot where Pine Island went down (at the 2006 Breeders Cup.) It was the isolated camera when she went down. One time and that was enough. There were people in the production truck that wanted to keep coming back to it and there were some arguments in the production truck.

"Ultimately what won was the side of 'Let's don't go there anymore.' We can show the horse on the racetrack to a limited extent as well. We basically showed her in the ambulance, a couple of shots of her standing on the track, a shot of the ambulance going off. At SportsCenter it's out of our hands but it's a situation where a couple of the biggest stories were there. And they were trying to cover that."

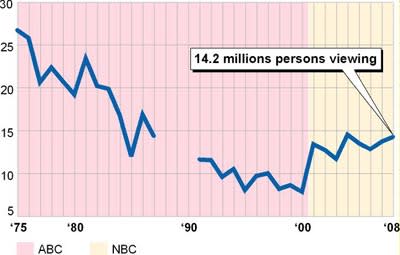

Kentucky Derby viewership

In millions of viewers:

Source: The Nielsen Company 2008. Data from 1988-90 not available.

Interestingly enough, it was the NBC's coverage of the event that provoked some of the most intense debate. Pictures of the breakdown came from the blimp camera rather than close-up shots. Critics excoriated the network for showing limited footage of the breakdown and accused NBC of trying to downplay the tragedy.

Others praised NBC, saying the more disturbing footage would not have been suitable for children watching the race on TV. Although it may be little comfort to those who found any of the images horrifying, far fewer people have watched the Kentucky Derby in recent years.

After the race, NBC reported that more than 14 million viewers had watched the Derby on TV, roughly the same number of viewers who watched the NCAA basketball championship and the final round of The Masters this year. What NBC failed to note is almost 27 million viewers watched the Derby in 1975, and, despite some fluctuation, ratings have experienced a steep decline.

If an ESPN survey conducted in 2007 to determine the most popular sports among males is right, horse racing ranks 13th – behind figure skating and extreme sports. But who's betting may be more important than who's watching.

Spencer Smith cheers as the horses come down the stretch at the Friday Night Races at Hollywood Park on May 9 in Inglewood, Calif.

(Michael Baker/For Yahoo! Sports)

COURTING YOUNGER FANS

On Friday night at Hollywood Park in Inglewood, Calif., young singles flowed through the upper level grandstand almost as fast as beer flowed through the taps. It was an encouraging sight for racing, but an exception to the rule.

Like many tracks around the country, Hollywood Park caters to the young on Friday nights with promotions such as $1 beers, $1 hot dogs and concerts after the final race. Spencer Smith, a 39-year-old mortgage broker who staked out tables near a bar for about 30 friends, said he has been attending the Friday night events since they began in 1991.

"Now if you come here on Saturday," Smith said, looking around at the throbbing crowd, "all the energy is gone."

So, for the most part, are the fans.

The Kentucky Derby, Preakness and Belmont each draw crowds in excess of 100,000. But the Triple Crown races provide a deceptive snapshot. Some tracks have stopped keeping track of how many fans trickle through the turnstiles, and Churchill Downs discloses attendance figures only on Derby day. Racing officials attribute the decline to horseplayers heading to off-track betting sites or staying home and wagering on the Internet. But generally speaking, a trip to the racetrack feels like a trip to an AARP convention.

Arnold Velazquez, left, talks on the phone while Robert Jojola looks at the racing program with Lauren Supernaw, left, and Nancy Alvarez at the Friday Night Races at Hollywood Park.

(Michael Baker/For Yahoo! Sports)

Demographics cited by the racing industry confirm the perception.

Sixty percent of racing fans are older than 45, and 20 percent of the sport's "core" fans are 65 or older, according to an ESPN survey. (ESPN and another company conduct the surveys for 30 sports, including the NFL, NBA and Major League Baseball.)

The survey showed racing has three million core fans, defined as those who place a bet at least once a month, and 20 million casual fans, defined as those who place a bet at least once a year, according to the NTRA.

"Our core fan base is older than the national norm," said Keith Chamblin, director of marketing for the NTRA. "We don't see that as either a positive or a negative. It's just a fact."

Yet at the same time, the NTRA said it began buying airtime for telecasts on ESPN in 1999 in an effort to tap into the network's young viewers. But cultivating young fans to replace the older generation of horseplayers remains tricky at best.

Del Mar Thoroughbred Club outside of San Diego is considered one of the most successful when it comes to attracting young crowds. Seven years ago they rebranded the track as a gathering spot for the hip and chic, in part with its slogan: "Cool As Ever."

Cool As Ever?

Ziggy Marley at the 2007 reggae festival at Del Mar.

(Photo courtesy Del Mar Thoroughbred Club)

"Everyone's first reaction is 'What in the hell does that have to do with horse racing? ' " said Craig Dado, director of marketing for Del Mar. "The answer is nothing. It has everything to do with our brand.

"When Bing Crosby opened the track in the 1930s and used to have all his Hollywood friends down here, this was a very cool place. And it still is."

One day last season, Del Mar brought in more than 35,000 fans. The big draw, however, stood on two feet, not four hooves.

His name: Ziggy Marley, the dreadlocked reggae star.

The 2007 reggae festival turned Del Mar into a mini-Woodstock. But while Del Mar and Hollywood Park report significant spikes in attendance during such special events, track officials acknowledge seeing only modest gains in wagering on those days. It seems the young fans enjoy the beer, hot dogs and festivities but bet small amounts of money.

"To get the guy who comes out for the reggae festival and try to get him to come out on a non-reggae day," Dado said, "that's my job."

That job has become increasingly difficult because of the changing landscape of the gambling industry.

COMPETING FOR GAMBLERS

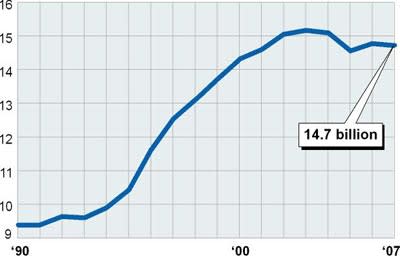

Money wagered on racing drops

On track and off track betting in the United States declined in 2007.

In billions of dollars:

Source: Jockey Club

Until the 1970s, outside of Nevada, the only place to wager legally was at the racetrack. The sport has lost that monopoly.

First came the state lotteries. Then casinos. Followed by card parlors, Internet gambling and horse racing helplessly watched the gambling dollar migrate elsewhere.

"Horse racing has kind of fallen into two categories culturally in this country, both of which are a little archaic," said Robert Thompson, a professor of sociology at Syracuse University who specializes in pop culture. "One is the category of the aristocratic Kentucky Derby. The second is of the gamblers that you would see in 'Guys and Dolls,' the kind of ne're do-well that are betting on the horses.

"Both of those are anachronistic. The notion of polite aristocratic society that would go to the races seems so 19th century, and I supposed the 'Guys and Dolls' notion of gamblers seems mid-20th century. Neither one of them seem 21th century."

Optimists point out that the sport took in $14.7 billion last year in the United States, and the figure is staggering. But handle – the term of pari-mutuel betting – has leveled off this decade. Signs of desperation: the New York Racing Association (NYRA), which controls Belmont Park and every other track in the state, filed for bankruptcy.

Salvation has come in the form of slot machines. More than a dozen states have granted tracks the right to operate the one-armed bandits, and the money has infused the tracks with much-needed cash. But research suggests it might be a stop-gap solution.

Few of the slot players are wagering on the horse races, as more and more casinos spring up across the country and offer more options for those presently headed for the tracks to play slots.

"What happens when gaming stops helping you?" said Tino Rieger, executive director of the Oklahoma Racing Commission. "What will you do then?"

SHIFTING VIEW OF HORSES

Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro looks out from his stall in the intensive care unit at the University of Pennsylvania's New Bolton Center for Large Animals in 2006.

(AP Photo/The University of Pennsylvania, Sabina Louise Pierce)

Jay Coakley, a prominent sports sociologist, said the outrage over Eight Belles underscores a cultural shift that could complicate racing's efforts to capture more of the gambling dollar.

"There's a general, increased sensitivity to issues related to animals and the well being of animals that are under the control of human beings," said Coakley, author of "Sport in Society: Issues and Controversies." "…The whole notion of using animals for sport is something young people feel less comfortable with today than in the past.

"The resistance to mistreatment of animals is much higher today than in the past as we have become less rural, as fewer of us have ever been on a farm, as any of us have ever seen animals born and die and work. As those experiences have become less and less frequent in our culture, we define animals differently."

When veterinarians worked to save Barbaro, thousands of people sent letters of encouragement – to the horse. An audiotape of Barbaro's victory still plays when callers are placed on hold at Churchill Downs. But the outpouring of sentiment of the horse signaled America's connection with the animal rather than new interest in heading to the betting window. Which may explain why racing officials are looking overseas.

GOING GLOBAL

Asia and the United Kingdom are markets in which the industry hopes to reach through simulcasts. Culturally, Coakley said, countries with stronger roots to rural life might be more likely to embrace the horse as an athlete.

"But you don't want to give up on your local fans," he said. "You always need a core of local fans in order to have immediate resources and also nurture and maintain the status associated with horse ownership. You need this subculture to provide people with motivation to invest their resources in the sport.

"But apart from that, if you're going to make money on this, you're going to have to look globally."

But less than two weeks removed the death of Eight Belles, the racing industry is squarely focused on Pimlico, where Kentucky Derby winner Big Brown will be poised to take another step toward the Triple Crown – and PETA will be poised to protest.

It's unlikely Hugh Hefner and his Playboy bunnies will attend, and at the moment the industry seems unconcerned about recasting its sport as sexy, hip and chic. For now, despite the serious challenges it faces to maintain its relevance, racing would be content to prove it's safe.