Rise of vicious Venezuelan prison gang sends migrants streaming toward U.S.

Cristian Cortes was already thinking about leaving Colombia to escape the gang violence ravaging his neighborhood when he came home to find a threatening flier shoved under his apartment door.

“Those who are snitches, we will blow up grenades in their cars,” it read. “No one will be safe inside their houses.”

The warning had been distributed by Tren de Aragua, a gang that has spread to half a dozen South American countries in the past few years after emerging from a Venezuelan prison around 2012. Wherever it has appeared, the gang has brought kidnapping, drug dealing, human trafficking, contract killings, and extortion along with it.

Tren de Aragua’s calling card is violence. It posts graphic videos on social media showing victims begging before being executed. Now, after a dispute with a local building management board in the Bogotá neighborhood where Cortes lived, the gang’s members were threatening to poison the water supply and set fire to elevators.

Cortes and 15 members of his family decided to flee.

“In Bogotá, every time I arrived in my neighborhood I had to hide everything — my money, my cell phone — because they could kill me for that,” Cortes said in an interview in a U.S. city, which he asked not to be revealed.

Tren de Aragua has grabbed headlines in recent years, mostly in Spanish-language media. But compared to other transnational gangs, such as MS-13 or the Sinaloa Cartel, the group has remained relatively unknown outside South America. Many aspects of its operations are still little-understood by analysts and law enforcement.

Drawing on a leak of documents from the Colombian prosecutor’s office, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and its partners, including the Miami Herald, have been able to piece together a picture that gives fresh insight into the gang’s operations.

This article is part of NarcoFiles: The New Criminal Order, a transnational investigation into modern organized crime and how it has innovated and spread throughout the globe.

Explore the full project here.

The reporting shows how Tren de Aragua has managed to go toe-to-toe with established groups, obtained heavy weaponry, and expanded outside its home country. The gang has set off a wave of terror in countries including Chile, Colombia, Brazil, and Peru, sometimes partnering up with other notorious gangs.

“They use excessive violence to demonstrate their power. The murder of whoever betrays or does not obey orders sets an example to others,” reads a police report detailing the gang’s history, which was included in the trove of documents from the Colombian prosecutor’s office.

In particular, Tren de Aragua has piled misery on Venezuelans who have already fled by the millions over the past decade to escape political turmoil, corruption, and an economic meltdown that has tipped into a humanitarian crisis.

READ MORE: Huge cyber leak offers new proof of how Maduro has turned Venezuela into a narco-state

Now there are signs that some Tren de Aragua members are even heading further north. The U.S. Border Patrol told OCCRP’s media partner CNN en Español that it has detained 38 suspected Tren de Aragua members in just one year, between October 2022 and 2023. At least two are being prosecuted for alleged illegal entry into the United States.

Spreading Terror

Tren de Aragua arose in the severely overcrowded Tocorón prison in Venezuela’s north-central Aragua state, most likely between 2012 and 2013, officials estimate. Due to neglect and corruption, authorities have largely ceded control of Tocorón to prisoners, who rule the facility through units known as “pranatos.”

Over the years, Tocorón became an international crime hub. In September, Venezuelan Interior Minister Remigio Ceballos told reporters that sniper rifles, grenades, rocket launchers have been found in the prison.

READ MORE: NarcoFiles: Dozens of DEA agents face risk of exposure in Colombian cyber leak

Humberto Prado, general coordinator of the Venezuelan Prisons Observatory, a rights group that monitors prison conditions in the country, said Tren de Aragua’s brutal tactics are rooted in practices the gang developed inside Tocorón.

He described the extreme lengths the gang would use to extract the “causa,” a tax from prisoners to allow them to live. “The first time you don’t pay, they shoot your wrist. If you don’t pay for a second time, they shoot your ankle. The third non-payment is the death penalty,” Prado said.

That kind of brutality has helped Tren de Aragua take over illicit sectors such as prostitution and drug trafficking in several South American cities.

One young woman told CNN en Español she had been forced into prostitution in Colombia by Tren de Aragua members, who tied her to a bed, drugged her, and starved her for two months. She said she was repeatedly raped by five men, and then forced to have sex with clients. Though she knew there were other women in nearby rooms, her only companions, she said, “were the mice.”

Óscar Naranjo, a former Colombian vice president and a retired police general who fought Pablo Escobar’s infamous Medellín cocaine cartel, said that Tren de Aragua is “the most disruptive organization in Latin America today.”

The gang’s tactics are reminiscent of those bad old days — bags of dismembered body parts and bodies buried under cement have turned up in Colombia and Chile, for example — but members are now able to amplify their terror even further, using social media.

In February this year, a video of the murder of a trans sex worker named Rubi Ferrer spread fear through the Peruvian capital of Lima. The video, taken on a phone, shows Ferrer begging for her life before she is shot point blank. Peruvian police attributed the killing to Tren de Aragua.

Ferrer’s murder, and the killing of another colleague named Priscila Aguado, was a message, according to Angela Villón, president of the Sex Workers Movement of Peru.

At the time, Villón said, the gang was attempting to take control of the sector in Lima, and sex workers had been warned to stop their activities. The gang was replacing them with women who fled conditions in Venezuela, but were desperately poor.

“After the threats came the deaths — the murders of Rubí Ferrer and Priscila Aguado. In one week they killed six women,” said Villón, who received the video of Ferrer’s killing on her phone.

Villón said around 18 of her colleagues have been shot in the feet as a warning to stop walking the streets. According to her organization, 24 sex workers were kidnapped or murdered in 2023 alone, while another 35 are missing.

Heavy Weapons

In another demonstration of the gang’s rapid expansion, a wave of murders broke out in 2021 in Boa Vista, capital of the Brazilian state of Roraima, which borders Venezuela and Guyana. Police identified a dozen killings in a five-month stretch from March to August 2021, all of which they attributed to Tren de Aragua.

The victims were Venezuelan migrants, and four of them had been dismembered. Prosecutors in Roraima said some victims may have owed drug debts, and that the murders were intended to “instill fear and terror” in the region.

A document obtained from the Roraima Public Security Secretariat, which oversees the state’s police, says that Tren de Aragua members are well armed, using machine guns and rifles.

In the document, the state’s secretariat — as well as the civil and military police — ask the Ministry of Justice and Public Security to provide “proportionate weaponry and ammunition to level the conditions for combating organized crime in the Amazon areas belonging to the state of Roraima.”

Over the weekend, USBP arrested 7 hardened criminals trying to enter the U.S.

1) w/ homicide conviction

2) w/ Assault Against Person & Hit & Run

3) Registered Sex Offender

4) El Sal Gang Member

5) Tren de Aragua Gang Member

6) Guatemalan w/ Warrant

7) Weapons Trafficker in Peru pic.twitter.com/ajLa03xBmt— Chief Jason Owens (@USBPChief) August 28, 2023

Tren de Aragua also used heavy weapons in Colombia in 2021. An army intelligence report included in the leaked documents from the Colombian prosecutor’s office says the gang used “assault rifles and fragmentation grenades” when it clashed with the National Liberation Army, a guerrilla group known by its Spanish-language acronym ELN.

The area around the city of Cucuta turned into what some locals called a “battle zone” as the groups fought for control over the La Parada border crossing with Venezuela. Eventually, the report said, Tren de Aragua “imposed its firepower, managing to establish itself in the place as the maximum controller of the illegal economy.”

Another report in the leak of Colombian prosecutors’ documents details the brutality meted out on those who betray the gang, such as Yonathan Zabalza Palencia, a Tren de Aragua member the gang had “marked” as an ELN “guerrillero.” Police found his dismembered body inside a sack that had been tossed into a canal.

In 2022, Colombia’s Attorney General announced the arrest in Bogotá of 19 alleged Tren de Aragua members, accusing them of murder, drug trafficking, bribery, extortion, and possessing illegal firearms.

“They want to show it, make it public, visible, to intimidate society as a whole,” said Naranjo, the retired police general.

Prison Crackdown

In September, Ceballos, the Venezuelan interior minister, told CNN en Español that authorities had “dismantled the leadership” of Tren de Aragua after a massive operation to take control of Tocorón prison.

The gang had run the prison for years, living in luxury off the proceeds of its crimes. Gang members had access to a swimming pool and several restaurants inside the facility, which also reportedly hosted a disco, a baseball diamond, a market, and a cock fighting ring.

Ceballos told journalists that the operation, which involved thousands of armed personnel, was a “complete success.”

But journalist Ronna Risquez, author of a recent book on Tren de Aragua, told OCCRP that while the raid would be a “hard blow,” it was unlikely that it would completely disrupt the gang.

“It does not mean the dismantling of the organization,” she said. “The leaders of the Tren de Aragua have not been arrested and it is not known where they are.”

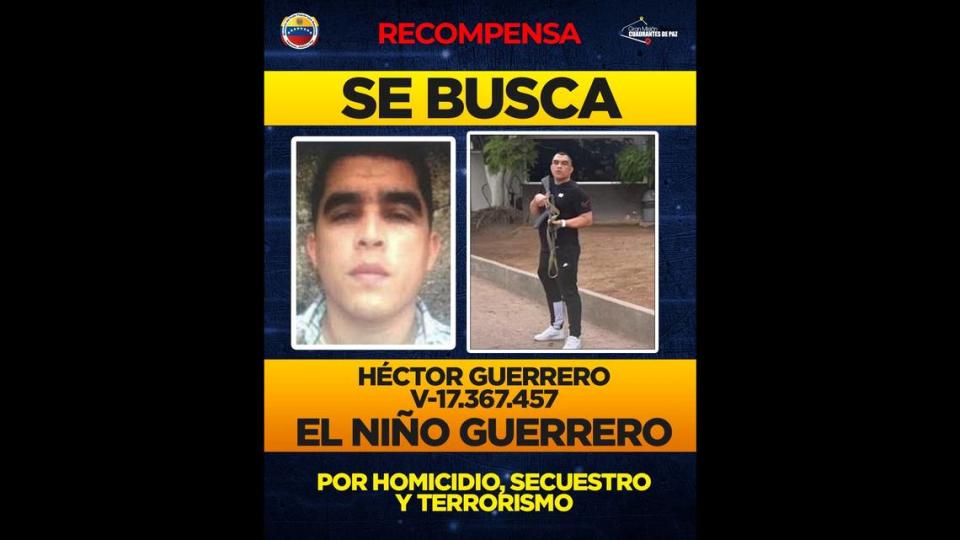

Arrest warrants have been issued in Peru and Colombia for Héctor Guerrero, known by his alias “Niño Guerrero,” who authorities say managed the group from Tocorón prison. His current whereabouts are unknown.

And now, as the U.S. Border Patrol statement suggests, there are also signs that the gang is starting to head further north.

That will be unwelcome news for people such as Juan, a Venezuelan who arrived recently in New York with his wife and three daughters. The family fled after his wife’s former husband, a Tren de Aragua member, gave an order for him to be killed.

Juan, 28, who used only his first name for safety reasons, said it was too risky to stay in South America, because gang members could have easily found him.

“They are already throughout Ecuador, through Colombia, through all those countries,” he said. “And here it is a little more difficult to enter, I think.”