The rise of car travel brought ‘tourist camps’ to Fort Worth. What the heck were they?

W. T. Casstevens made a career out of the job opportunities produced by new technology. In his case, it was cars.

Early automobiles had a reputation for breaking down on rough, often unpaved, roads. Casstevens started his career as a streetcar conductor, but became an automobile mechanic during the early years of the automobile industry.

He then switched to selling used cars. Many of the automobiles he bought were junkers, so Casstevens decided that turning his business at 508 North Main into an auto parts salvage yard would be more profitable. He boasted that, “We tear ‘em up and sell the pieces.” He also opened a gas station, another necessity for travelers.

Randy Casstevens, remembers his great uncle as a dapper man who wore a diamond pinkie ring and was a professional gambler. He bought and sold large pieces of land and always entertained new business opportunities. For a time, W. T. and his wife Euzella lived on Park Place in Berkeley, just south of downtown Fort Worth, but later settled around other family members on Casstevens Street in Westworth Village, west of downtown.

Transcontinental highway comes through Fort Worth

During the late teens, planners decided to run the nation’s first all-weather, transcontinental highway through Fort Worth. It was named for Alabama senator John H. Bankhead. The Bankhead Highway was also designated as Texas Highway No. 1 within the state. The Bankhead name was used until 1939, when much of the route was designated as U. S. Highway 80.

Rather than build an all-new highway, the Bankhead sought to link stretches of existing roadway with sections of new construction. The early Bankhead route ran along Vickery Boulevard, but it later switched to one which went down West Seventh and along Camp Bowie Boulevard past the city limits and on to Weatherford and Mineral Wells.

New construction was needed just west of the Fort Worth city limits, so Camp Bowie was extended in 1930.

Roadside amenities grow with auto travel

Travelers could now take long-distance car trips. In addition to taking care of their automobiles, they needed a place to sleep and eat, and Casstevens was happy address those needs.

Early tourist camps were often literally just that – camping sites. Thus, the name. But travelers wanted better accommodations than camping offered. Tourist camps or courts soon offered sleeping rooms that looked very different from downtown hotels. They were usually one-story buildings with a place to park the car near the room. They gave the traveler a “haven of comfort and rest” suitable for a short stay.

Casstevens wasn’t the first to put a “tourist camp” along the Bankhead route, but he had one of the earliest lodgings on the west side of the city limits. One of the first tourist camps in town was the AA Tourist Camp at 2136 West Seventh St. (west end of the Seventh street bridge), which opened in mid-1927.

Casstevens preferred a location he already owned – his farm just outside of the western city limits, which had electrical service and a water well. He opened Cottage City by December of 1927, and the water tank was a landmark on the almost empty horizon.

His 1929 postcard, printed in economical black ink, shows Cottage City’s location along the Bankhead with Fort Worth smokestacks (which then suggested prosperity as opposed to pollution) in the background.

Cottage City was a series of bungalow cottages with a restaurant and gas station. It was located in what is now the 6000 block of Camp Bowie Boulevard on the south side of the street – roughly where the Exxon gas station next to the Ridglea Theater now stands.

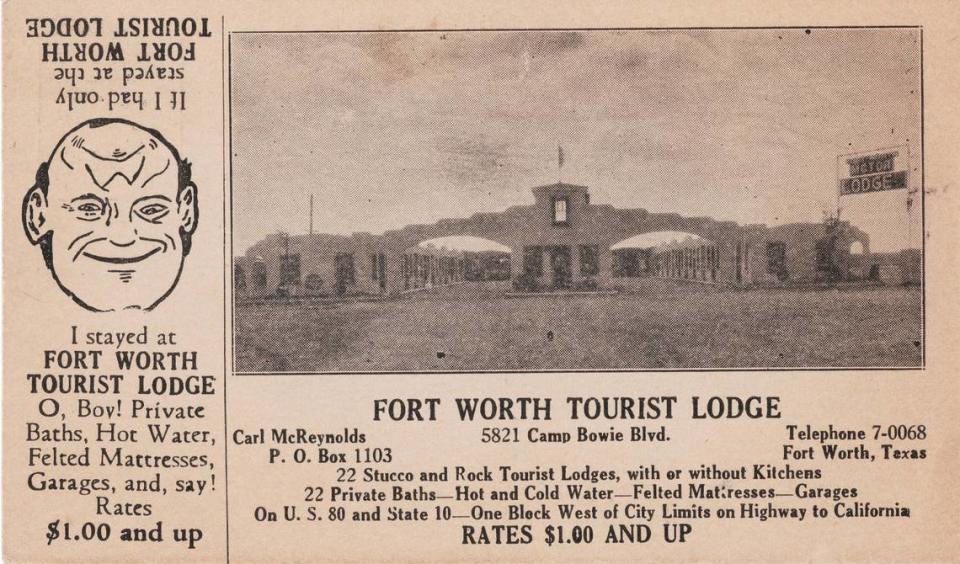

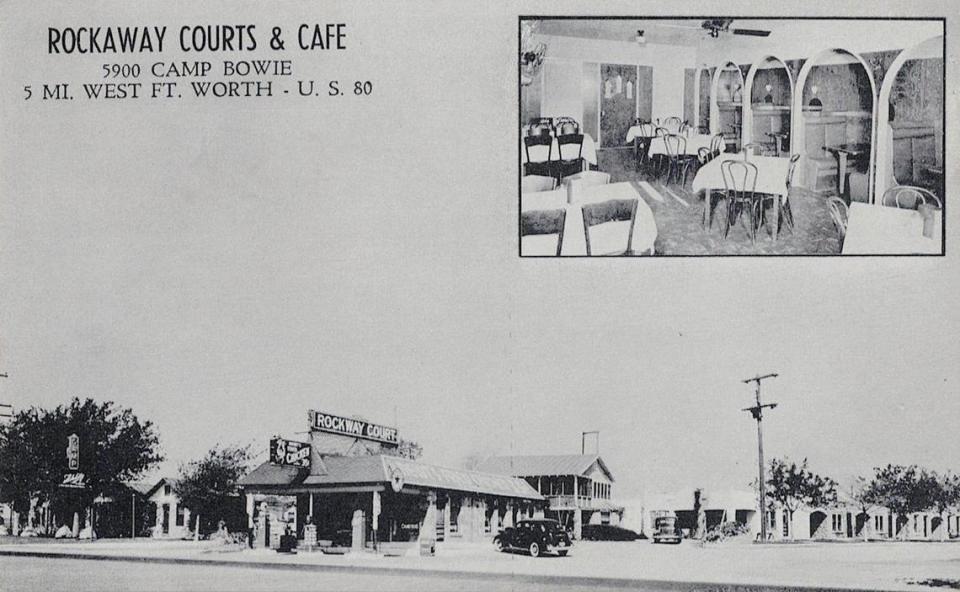

A bit closer to town, at 5821 Camp Bowie Blvd., the Fort Worth Tourist Lodge run by Carl McReynolds was completed in 1930. McReynolds’ finances were strained, and he did not get his operation established before the Great Depression hit. By 1933 he was asking potential buyers to, “make [him] an offer.” Two slightly later tourist courts (the general name evolved from camp to court) in this area included Rockaway Courts & Café (5900 Camp Bowie) and the Hatch Brothers Tourist Court (5800 Camp Bowie).

A 1930 photograph that shows Camp Bowie Boulevard looking west includes three of the tourist lodges and the boulevard under construction. This was a part of Camp Bowie outside the city limits and past where the streetcar ran to Arlington Heights. The Highway Department paved this section of the highway with brick in 1930. It was heralded as a “Gateway to West Texas.”

Tourist lodges become temporary homes

As the Great Depression deepened, families traveling west became economic migrants rather than travelers. Sometimes, when travelers ran out of money, they plopped down in a tourist court and looked for work.

Cottage City became Fort Worth’s official housing place for transient families between 1933 and 1937. There were also separate facilities at other locations in town for single men, women, and Black people. Men were sent to work projects, while educational courses were offered for women and children.

The tenant mix changed again once World War II started. Most were employed in the defense industry, but all were longer term residents. Rationing made long distance travel difficult unless it was for war work.

By the war’s end, older tourist courts were being eclipsed by the latest thing in travel lodging – motels. Highway 80 (which followed the Bankhead route in this part of town, but took a different path elsewhere) collected a dazzling array of u-shaped courtyard motels with a swimming pool and fantastic neon signs. Many still remain, though their glory days have passed.

Casstevens remodeled and expanded Cottage City over the years and eventually changed its name to Casstevens Hotel and Courts. Many occupants were long term tenants seeking an affordable place to live. Casstevens Hotel survived the 1954 explosion of a hot water heater, which rocketed through an exterior wall, but it didn’t outlive the expansion of Ridglea with its juggernaut of commercial development along Camp Bowie and surrounding residences.

Note: Special thanks are due to Dan L. Smith and Marcel Quimby for their work on the Bankhead Highway history.

Carol Roark is an archivist, historian, and author with a special interest in architectural and photographic history who has written several books on Fort Worth history.