Have RI's cozy local libraries become ground zero in the culture wars?

PROVIDENCE − Quick: what are the first words that come to mind when you think of your cozy, well-lit leather-chaired local library?

Censorship? Book banning? A neo-Nazi flag-waving rally for an all-white New England? Didn't think so.

And yet, those words straight out of a dystopian novel have made headlines in Rhode Island, Connecticut and beyond, have prompted recent debate at the State House over a bill to shield librarians from harassment and prosecution, and even led a former Rhode Island legislator to write a book documenting the citizen-led war that saved Providence's neighborhood libraries.

Can't happen here?

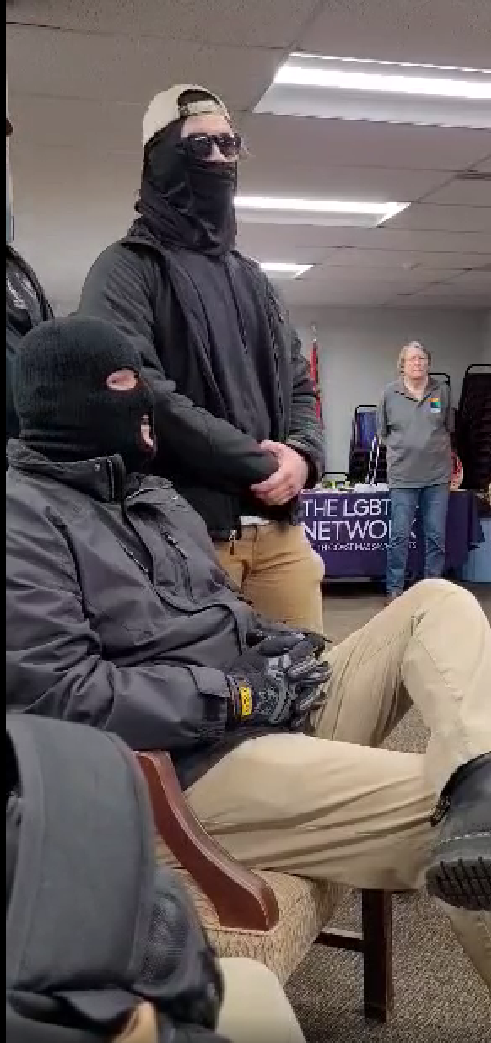

In late February, 15 to 20 members of the People’s Initiative of New England (PINE), an extension of the neo-Nazi National Socialist Club 131, handed out flyers outside the Cumberland Public Library and other town sites, according to The Valley Breeze.

The flyers called for an “end [to] all non-white migration to New England." According to their handout, the group wants the six New England states "formally recognized as a white homeland and a sovereign state."

"A new national party will be established for the government of New England."

It is not clear why the mask-wearing visitors, who arrived in vehicles with New Hampshire and Connecticut license plates, chose the sidewalk outside the governor's hometown public library for their flag-waving demonstration.

Library director Celeste Dyer believes they may simply have stopped where they saw activity after posing for the pictures they posted online of themselves next to Nine Men's Misery, a monument on the same former monastery property that marks the spot where nine Colonists were captured and killed by the Wampanoag tribe during King Philip's War.

Whatever led them there, Dyer said, their presence – and their message – made the library patrons uncomfortable.

Reading one of their pamphlets, "we were all horrified,'' Dyer told Political Scene. "But they have the right to say what they want to say. We just don't have to listen if we don't want to."

PINE posted its own takeaway from the visit online: "Passerby loved the flags and welcomed the volunteers with honks and waves. Many fruitful conversations were held, and New Englanders were overwhelmingly receptive to the message of New England Nationalism!"

More: Rhode Island saw a huge increase in white supremacist incidents last year. Who's behind it?

The school library fight comes to Rhode Island

On Thursday, Feb. 29, Rep. Jennifer Stewart − a history teacher from Pawtucket who is no stranger to controversy − went to bat for a bill (H7386) she calls "Freedom to Read."

If it became law, her bill would prohibit "the practice of banning, removing, censoring or otherwise restricting access to specific books or resources due to partisan or doctrinal disapproval."

"I think a bill like this shouldn't be needed," she told fellow legislators on the House Committee on State Government & Elections.

But "you're going to hear testimony tonight from several people about why it is in fact needed as a protective measure and as an important statement of the democratic values of Rhode Island."

More: Moms for Liberty to advise librarians on book removals in Florida

Scores of defenders – including former and current teachers and librarians from across the state – wrote or turned out in person to support the bill, including former high school teacher Cassidy Sandberg, who wrote:

"Books are everything. They are a place to go for escapism to an imaginary place. They are a resource for information and learning. They are informative entertainment. They are [h]istory. They are culture. They cultivate understanding but have also been known to cultivate hate."

"Regardless, they should not be censored," she wrote.

"Most of the challenges we see nationwide are against books written by or about a person of color or a member of the LGBTQIA+ community," Cheryl Space, library director at the Community Libraries of Providence, told the legislators.

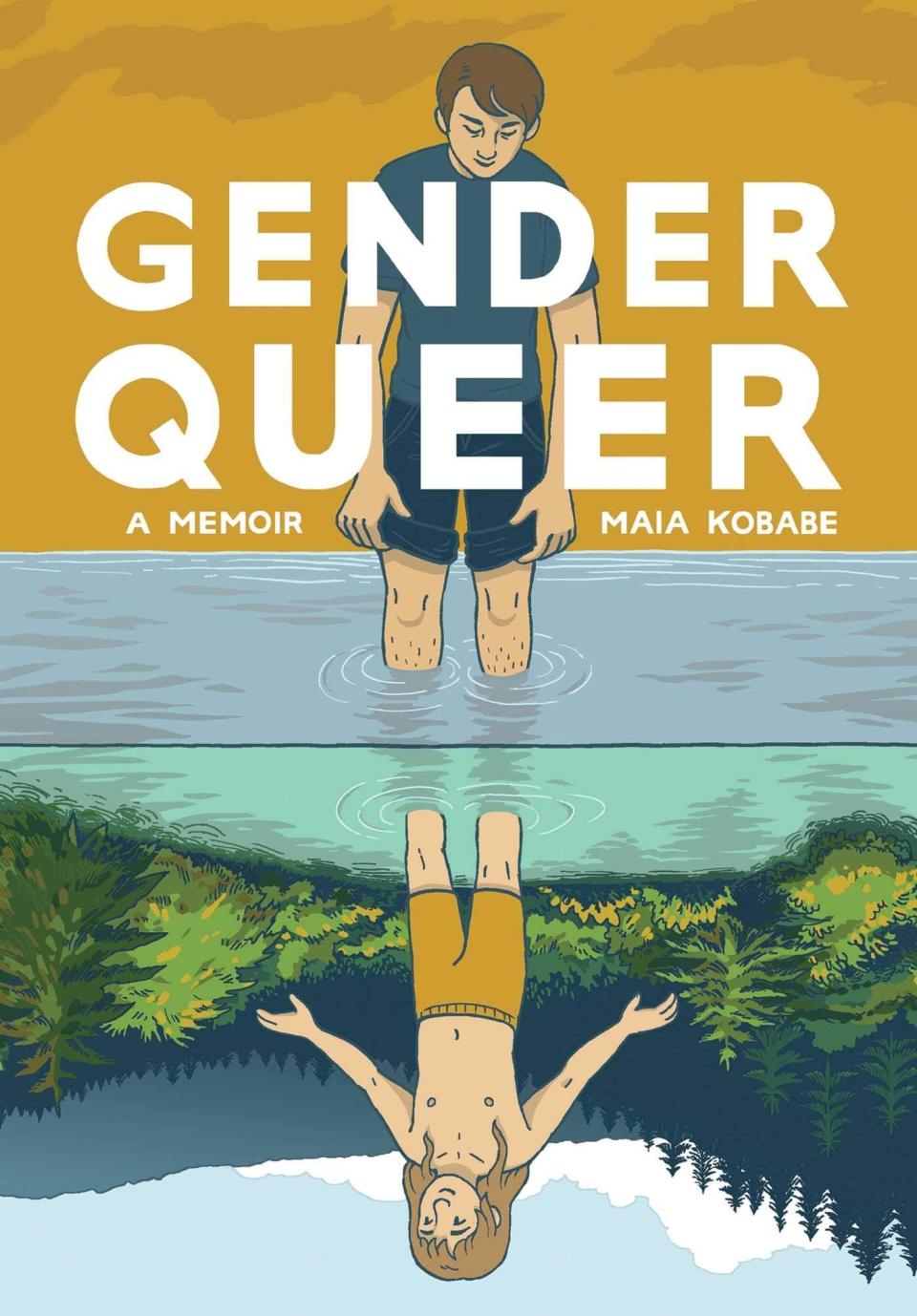

On cue, the protagonists on both sides of the heated debate in Westerly over a book titled "Gender Queer" took turns at the microphone.

On one side: Marianne Mirando, the Westerly high school librarian who put “Gender Queer: A Memoir” on the shelves and said no one has the right to pull books that others might want to read. On the other side: Robert Chiaradio, who filed a complaint with the Westerly police alleging violations of obscenity law by school officials, including Mirando.

Mirando said she was subjected to harassing phone calls and "a slanderous email" after the effort.

"I kept telling myself, it'll be fine," she said. "I live in New England, [but] frankly, if I was a younger librarian, that would've been even more difficult to withstand."

During her long career as a librarian, Mirando told legislators that she has never seen anything like the book censorship movement led by "the ironically entitled Moms for Liberty" and "fanatics who assume that their interests should supersede [others'] First Amendment rights."

Every library contains books that some people like, or don't like, she said. The books targeted for censorship are typically ones about "historically underrepresented groups" she said, or marginalized people.

"Reading provides information, expands knowledge, nurtures empathy, and empowers learners. Why would anyone want to limit that?" she asked.

On the other side, Chiaradio stood firm in his stated belief that books can be corrupting and the American Library Association is pushing bills like this to "actually codify [the] sexualization and indoctrination of Rhode Island's youth, which in ... my view will lead to the destruction of these kids [and] the family unit as we know it."

As he sees it, Stewart's bill would allow books depicting "vulgarity, pedophilia and other sexual acts" to be put in public libraries with no outside input, and only at the discretion of the librarian.

"I think it's a terrible bill like Rep. [Brian] Newberry said, and I think it should be torn up and thrown in the trash," said Chiaradio.

In his turn, Newberry asked: Why is this needed? (Stewart: "There have been four attempts to try to censor the holdings of libraries in the state").

Newberry also asked each speaker: "The public entity is paid for by public tax dollars. ... So why can't the people who pay for that [at] least have a say?"

The ACLU's Steven Brown provided one answer: the wording of a 1982 U.S. Supreme Court opinion:

"We hold that local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to prescribe what shall be Orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion."

"That's what this is all about," Brown said.

New book documents fight to save Providence's libraries

Former Rep. Linda Kushner has written a bite-sized book that documents what almost, but did not, happen in Providence two decades ago – and her role in preventing it.

Titled "The Fight that Saved the Libraries," the book, set for release by Stillwater River Publishers in May, recounts the five-year battle Kushner and others won to keep the nine branch libraries in Providence open.

The short version: The Providence Public Library was a private corporation with a public purpose, supported over the years by both private donations and city and state dollars.

By 2004, state and municipal dollars constituted 61% of the operating budget of the Providence Public Library, yet, as Kushner writes, "its decisions were made by a private board at closed meetings with no input from the public it was designed to serve."

The book is most fun when Kushner talks about the nine branch libraries as windows into Providence's changing neighborhoods:

At Rochambeau, where Russian immigrants settled in the 1980s and 1990s, men would gather to wait for the library to open so they could read the library's Russian-language newspapers. Their discussions, Kushner writes, grew "so animated" that the librarians gave them their own small, closed-off room that became known as the Russian Room.

An influx of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the 1990s "created a demand for books in Spanish at the South Providence, Washington Park, and Knight Memorial branches.

Hmong and other South Asian refugees fleeing the Vietnam War in the 1960s arrived in Providence, settling around St. Michael's Church in South Providence and on Smith Hill. Those neighborhood libraries hung the "colorful handmade wall-hangings made by the Hmong, documenting the refugees’ experiences" on the walls.

What was happening behind the scenes was another story, which Kushner tells in detail from her perspective.

By July 2004, the Providence Public Library had cut 21 librarians and 14 clerical workers and slashed hours at the Central Library, eliminating all Saturday hours and most weekday evening hours.

The branches also had their hours slashed, with the larger libraries only open 45 hours a week and smaller ones 30.5 hours.

The response to the layoffs and cuts from the public was "immediate and fierce," Kushner wrote, especially after learning from IRS filings that, "while crying poverty," the Providence Public Library, "from 1998 and 2002 had increased the top five administrator’s salaries by roughly 12% a year."

Then more came out, including "the fact that PPL had over $35 million in unrestricted funds."

"It was an eye opener for the reading public including, I am sure, members of the Providence City Council," Kushner wrote.

And yet it took another five years for a new nonprofit group, the Providence Community Library, to take over the nine branches. Roofs were fixed and fire protection was installed after the buildings were subsequently transferred to the city.

How all that happened is a textbook case of a never-say-die fight to save the local libraries.

What has happened since is what Kushner describes as a revolution.

ESL (English as a second language) classes were added to the "library menu" at a point in time when 38.1% of Providence’s residents were of Latino descent. Then came GED (high school equivalency), computer and citizenship classes.

The book begins, and essentially ends with this lookback by Kushner: "I never, ever in my life thought I’d be the mother of a library system."

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: How Rhode Island's libraries are in the middle of political fights