Ringling College of Art students learn forensic sculpting using skulls from cold cases

A small group of students, faculty and alumni from Ringling College of Art and Design gathered during spring break last week for a unique, week-long workshop. However, the highly artistic participants were asked to put their creativity on a shelf.

Joe Mullins, Senior Forensic Imaging Specialist with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, led the Forensic Skull Sculpture Workshop. Mullins told the participants, “Everybody line up and you're giving me your artistic license. You're cashing it in. It's being revoked for this class, because the reason is, as you do this, it's not a creative class.”

Mullins worked with the District 21 Medical Examiner’s Office, which covers Lee, Hendry and Glades Counties, to try to solve some cold cases. Twelve skulls from the medical examiner’s unidentified death investigations were scanned and replicated with a 3D printer at Ringling College. Two other cases came from a medical examiner in New York.

Each student is worked with a replica of an actual unsolved case. Students received limited information about the unidentified person. They were told if it was a male or female, an estimated age range and possible race. In some cases, the medical examiner knew the length and color of hair. If clothes were recovered with the body, they may have had an idea of the person’s weight. In any case, it wasn't much to go on.

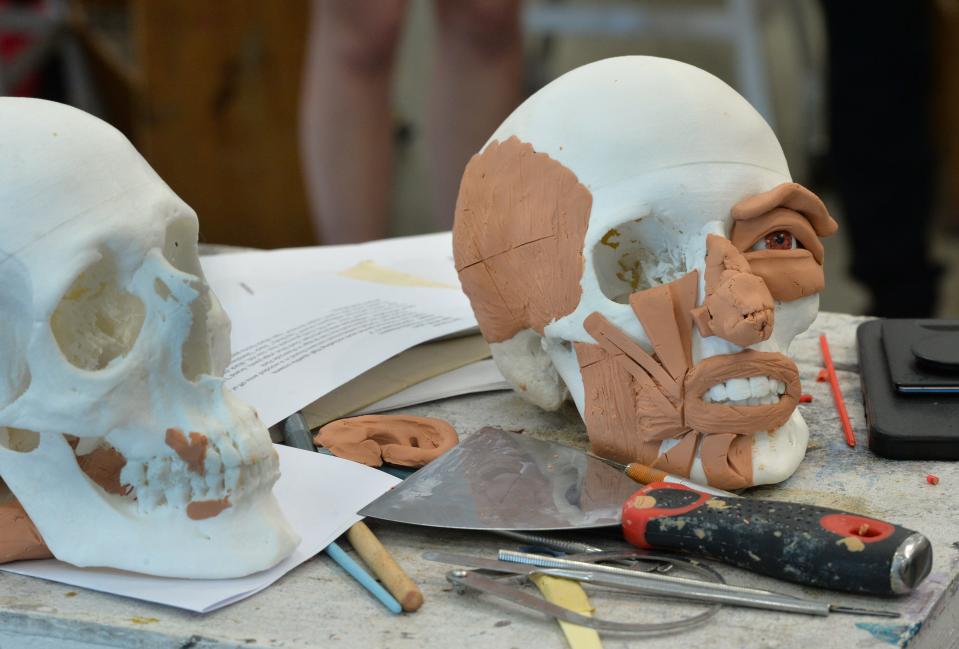

From the bare skull, students began sculpting from the inside out, following human anatomy and data from forensic anthropologists.

“They start adding muscles, then slowly build it out, dictating what that skull is telling us about the projection of your nose, the width of your nose, thickness of your lips, whether you have attached or detached earlobes. Your skull is the foundation that you're built on. That's everything about you is being represented by your face, but it's etched into your skull. So that's where that forensic anthropologists can pick up the skull and give us those parameters. So this is amazing detail that we're given, but we still have to represent in more of an ambiguous way. You can’t go too far off the rails.”

Third-year illustration major Noah Shadowens said the workshop will help with his drawing. “You can look at as many anatomy books as you want. But we built the muscles and now I know exactly where they go”, he said. “Joe told us, 'After this, you will look at people differently.'”

“We’re just teaching fine artists how to be a forensic artist in this week-long class, because they're really getting an education on how to be a forensic artist. It's just like a superpower that's been laying dormant.” Mullins says.

Mullins adds the students have to resist the urge to make their work pretty and perfect. “There's no artistic license. If the skull isn't telling you to do it, you can't sculpt it.”

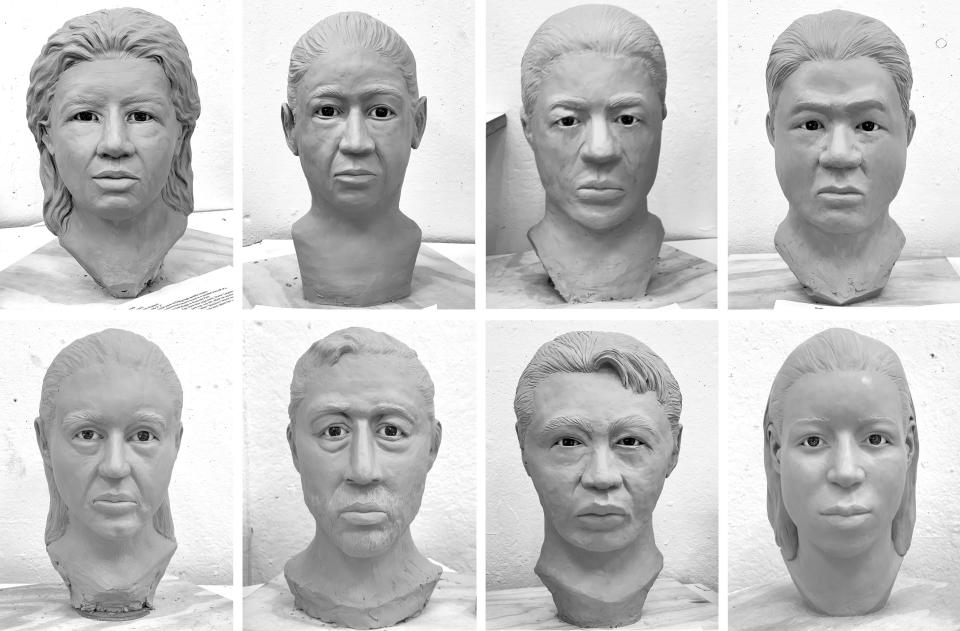

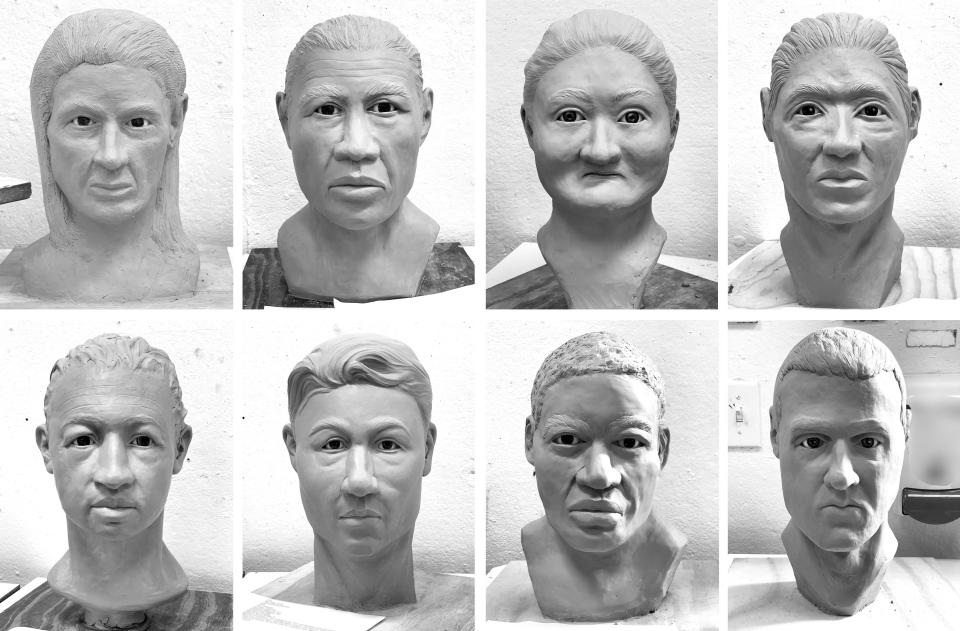

Mullins explains, “At the end of the week, everybody has to hit the parameters for these active cases with the information they have in front of them, so if somebody's working on a 30- to 40-year-old Caucasian male with short hair and a medium build, when it's all said and done, that's a facial approximation that they've created from that bare skull to this finished clay bust. If I show it to you and you say, 'Oh, it looks like a black male, like a teenager,' then they've missed the mark. So, with that in mind, there's no artistic license. If I issued that creative license, then just turned them loose, they could sculpt a beautiful representation – a beautiful bust – but it doesn’t look like the skull that’s underneath.”

"The sole purpose of this class is to utilize the talent here at Ringling, the mix of alumni, staff and current students here, to lend their abilities to help these coldest of the cold cases. To help put a face that's recognizable and now that the answers for these families that have been out there feel not knowing what happened to their family member for 5, 10, 15, 20, some of these 30-plus years.” Mullins said. “This mission is to give these people their identity back. They were born with a name. They deserve to die with one. So that's really the purpose of this class.”

The finished sculptures will be displayed in the Special Collections section of the Goldstein Library on the campus of the Ringling College of Art and Design beginning on April 8 and run through April 26. If you think you recognize any of the faces below as a possible missing person, please contact National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) at namus.nij.ojp.gov/

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Cold case: Ringling art students use forensic sculpting from skulls