New research could help predict the next solar flare

Newly published research could help predict when there will be "powerful solar storms."

According to Northwestern's McCormick School of Engineering, an international team of researchers found that the sun’s magnetic field starts around 20,000 miles below its surface. Previously, the magnetic field was thought to have originated 130,000 miles below its surface.

According to NASA, the sun's magnetic field is created by a magnetic dynamo that is inside of it. This study aimed to prove that the dynamo actually begins near the sun's surface. Researchers hope that a better understanding of the sun's dynamo could help predict future solar flares.

“This work proposes a new hypothesis for how the sun’s magnetic field is generated that better matches solar observations, and, we hope, could be used to make better predictions of solar activity," said the study's co-author Daniel Lecoanet, an assistant professor of engineering sciences and applied mathematics, researcher at the McCormick School of Engineering and a member of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics.

It's an age-old question that astronomer Galileo Galilei tried to answer, but hundreds of years later, researchers say they found the answer and published the findings in the journal, Nature.

“Understanding the origin of the sun’s magnetic field has been an open question since Galileo and is important for predicting future solar activity, like flares that could hit the Earth,” Lecoanet said.

What is a solar flare?

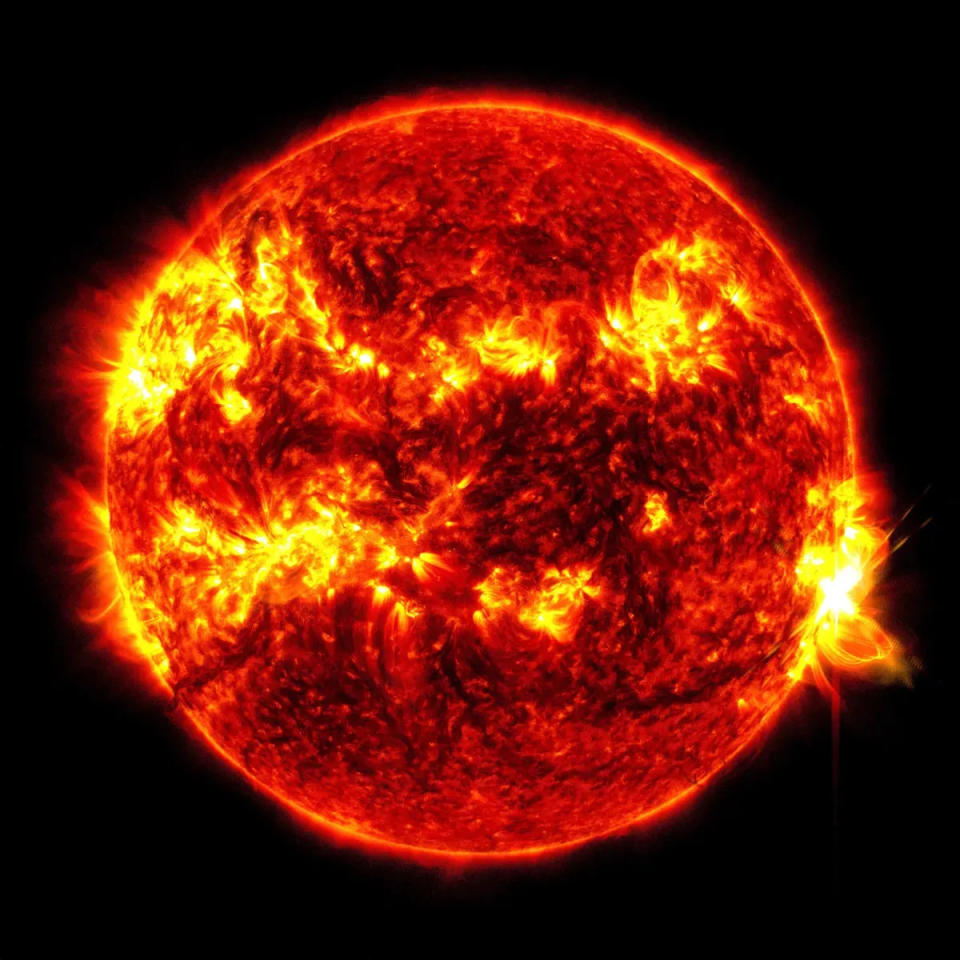

A solar flare is an explosion of radiation that is produced by the sun and can result in solar storms

Recently, the same powerful solar storm that created the bewildering Northern Lights seen across North America, affected farmers' equipment at the height of planting season. Machines and tools that rely on GPS, like tractors, glitched and struggled with navigational issues.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also warned that it could disrupt communications.

Pretty and damaging

While solar flares can cause phenomena such as the aurora borealis that captured attention at the beginning of May, they can cause a lot of damage, too. This is why it's important for researchers to be able to predict when they will hit.

"Although this month’s strong solar storms released beautiful, extended views of the Northern Lights, similar storms can cause intense destruction," said the school in a statement.

According to the university, solar flares can damage the following:

Earth-orbiting satellites

Electricity grids

Radio communications.

How was it calculated?

For their study, researchers ran complex calculations on a NASA supercomputer to discover where the magnetic field is generated.

To figure out where these flares originated, researchers developed "state-of-the-art numerical simulations to model the sun’s magnetic field," states the school.

This new model now takes torsional oscillations into account. It correlates with magnetic activity and is a phenomenon in the sun "in which the solar rotation is periodically sped up or slowed down in certain zones of latitude while elsewhere the rotation remains essentially steady," states a different study.

The sun is super active

The sun is at its solar maximum, meaning it is reaching the height of its 11-year cycle and is at the highest rate of solar activity.

Folks can expect to see more solar flares and solar activity, including solar storms.

Contributing: Eric Lagatta, USA TODAY

Julia is a trending reporter for USA TODAY. She has covered various topics, from local businesses and government in her hometown, Miami, to tech and pop culture. You can connect with her on LinkedIn or follow her on X, formerly Twitter, Instagram and TikTok: @juliamariegz

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: When's the next solar flare? New research could help predict that