How Republicans Echo Antisemitic Tropes Despite Declaring Support for Israel

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Republican speaker of the House, Mike Johnson, traveled to Columbia University two weeks ago to decry the “virus of antisemitism” that he said pro-Palestinian protesters were spreading across the country. “They have chased down Jewish students. They have mocked them and reviled them,” he said to jeers from protesters. “They have shouted racial epithets. They have screamed at those who bear the Star of David.”

Former President Donald Trump chimed in. President Joe Biden, he wrote on Truth Social, “HATES Israel and Hates the Jewish people.”

Amid the widening protests and the unease, if not fear, among many Jews, Republicans have sought to seize the political advantage by portraying themselves as the true protectors of Israel and Jews under assault from the progressive left.

Sign up for The Morning newsletter from the New York Times

While largely peaceful, the campus protests over Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip that has killed tens of thousands have been loud and disruptive and have at times taken on a sharpened edge. Jewish students have been shouted at to return to Poland, where Nazis killed 3 million Jews during the Holocaust. There are chants and signs in support of Hamas, whose attack on Israel sparked the current war. A leader of the Columbia protests declared in a video that “Zionists don’t deserve to live.”

Debate rages over the extent to which the protests on the political left constitute coded or even direct attacks on Jews. But far less attention has been paid to a trend on the right: For all of their rhetoric of the moment, increasingly through the Trump era many Republicans have helped inject into the mainstream thinly veiled anti-Jewish messages with deep historical roots.

The conspiracy theory taking on fresh currency is one that dates back hundreds of years and has perennially bubbled into view: that a shady cabal of wealthy Jews secretly controls events and institutions contrary to the national interest of whatever country it is operating in.

The current formulation of the trope taps into the populist loathing of an elite “ruling class.” “Globalists” or “globalist elites” are blamed for everything from Black Lives Matter to the influx of migrants across the southern border, often described as a plot to replace native-born Americans with foreigners who will vote for Democrats. The favored personification of the globalist enemy is George Soros, the 93-year-old Hungarian American Jewish financier and Holocaust survivor who has spent billions in support of liberal causes and democratic institutions.

This language is hardly new — Soros became a boogeyman of the American far right long before the ascendancy of Trump. And the elected officials now invoking him or the globalists rarely, if ever, directly mention Jews or blame them outright. Some of them may not immediately understand the antisemitic resonance of the meme, and in some cases its use may simply be reflexive political rhetoric. But its rising ubiquity reflects the breaking down of old guardrails on all types of degrading speech, and the cross-pollination with the raw, sometimes hate-filled speech of the extreme right, in a party under the sway of the norm-defying former, and perhaps future, president.

In a July 2023 email to supporters, the Trump campaign employed an image that bears striking resemblance to a Nazi-era cartoon of a hooknosed puppet master manipulating world figures: Soros as puppet master, pulling the strings controlling Biden.

To take a measure of the drumbeat of the cabal conspiracy theory among elected officials, The New York Times reviewed about five years of campaign emails from Trump, as well as news releases, tweets and newsletters of members of Congress over the last decade.

The review found that last year at least 790 emails from Trump to his supporters invoked Soros or globalists conspiratorially, a meteoric rise from prior years. The Times also found that House and Senate Republicans increasingly used “Soros” and “globalist” in ways that evoked the historical tropes, from just a handful of messages in 2013 to more than 300 messages from 79 members in 2023.

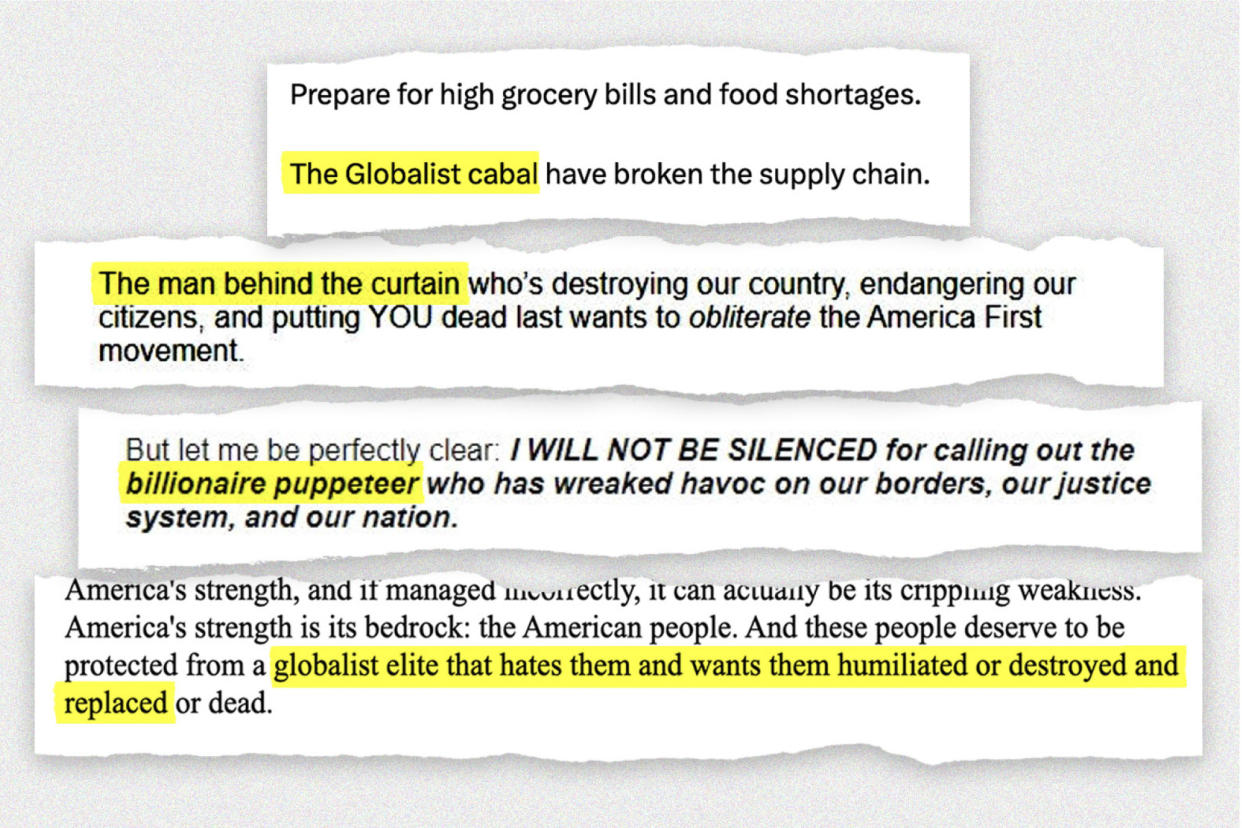

Trump frequently referred to Soros as “shadowy” and “the man behind the curtain who’s destroying our country.” He linked Soros and other enemies to a “globalist cabal,” echoing the trope that Jews secretly control the world’s financial and political systems — an idea espoused in “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” a fraudulent document used by Josef Stalin and the Nazis as a rationale for targeting Jews. Republican members of Congress repeatedly made incendiary and conspiratorial claims about Soros and globalists — that they were “evil,” that they “hate America” and that they wanted the American people to be “humiliated or destroyed and replaced or dead.” Republicans blamed them for leading people to “forget about God and family values,” for controlling the media, for allowing “violent criminals and rapists to get off scot-free” and more.

Conservative lawmakers dispute the notion that invoking Soros and globalists is antisemitic. “Not every criticism of Mr. Soros is antisemitic,” said Rep. Matt Gaetz, R-Fla. “Every criticism of Mr. Soros that I have levied is directed specifically at his flawed policy goals.” What’s more, he said, “I regularly criticize globalists of all faiths.”

Republican elected officials also point to their longstanding support for Israel. “Jewish Americans and Jewish leaders around the world recognize that President Trump did more for them and the state of Israel than any president in history,” said a spokesperson for Trump. She added, “Joe Biden can’t stand up to antisemitism in his own Democrat Party — primarily because his biggest donors like George Soros help fund it.”

Dov Waxman, a professor of Israel studies at UCLA, said Trump and other Republicans “are presenting themselves as committed to fighting antisemitism, but they’re actually mainstreaming some of the most antisemitic ideas in circulation today.”

That duality was encapsulated on the day the House speaker visited Columbia. Trump, speaking to reporters that evening at the New York City courthouse where he is on trial, amped up his criticism of the campus protests — and added a twist: He compared them to the violent 2017 march in Charlottesville, Virginia, where torch-bearing white supremacists chanted, “Jews will not replace us.” At the time, he sought to minimize the deadly Charlottesville rally by saying there were “very fine people on both sides.” Now, he called it “a little peanut,” adding: “The hate wasn’t the kind of hate that you have here. This is tremendous hate.”

Oct. 7 Creates an Opening

From campuses in turmoil to the halls of Congress, activism on the left has ignited ever-more-fevered debate over the meaning, propriety and limits of language.

Chief among the phrases at issue is “From the river to the sea, Palestine must be free,” which has become a mantra of the campus protests. While pro-Palestine activists describe the chant as a rallying cry for Palestinian liberation, to many supporters of Israel it signals a call for the destruction of the Jewish state.

Indeed, the pro-Palestinian movement has long faced accusations that its criticism of Israeli policy, particularly its opposition to the idea of a Jewish homeland on disputed territory, amounts to prejudice against Jews.

In November, the Republican-led House, with support from 22 Democrats, censured Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich., Congress’s sole Palestinian American, for her statements after the Hamas attack, including “from the river to the sea.”

(The Times’ review of lawmakers’ statements found roughly 20 from the last decade by a handful of Democrats, including Tlaib, that could be construed as antisemitic. These included “from the river to the sea,” as well as messages that Israel was a colonialist state or that lobbyist money was the driving force behind political support for Israel.)

In response to her censure, Tlaib said her criticisms were of Israel’s government, not Jews. “The idea that criticizing the government of Israel is antisemitic sets a very dangerous precedent, and it’s being used to silence diverse voices speaking up for human rights across our nation,” she said.

But the new surge of pro-Palestinian activism in traditionally left-wing spaces like college campuses has left some American Jews feeling especially vulnerable, an anxiety that has only grown as the protests and the efforts to shut them down have become more confrontational. In the wake of the Hamas attack, many have been stunned by what they see as a lack of empathy or solidarity from groups and people they had previously considered allies.

Accompanying the campus protests — and the furor surrounding them — have been sharp increases in reports of antisemitic incidents on a broader national canvas.

In 2023, the Anti-Defamation League reported more than 8,800 instances of anti-Jewish violence, harassment and vandalism, the most since it began tracking incidents in 1979 and a 140% increase from the record set the previous year. The tally included a 30% increase in antisemitic propaganda from white supremacists, from 852 incidents in 2022 to 1,112 in 2023.

The ADL’s new figures, however, reflect the heightened sensitivities over language: After Oct. 7, as the Forward first reported, the ADL broadened its criteria to include more “anti-Zionist chants and slogans” at rallies.

“For us, the context has changed,” explained Oren Segal, vice president of the ADL Center on Extremism. “After a massacre that kills 1,200 Israelis, we were including more of those expressions in support for terror, more of the calls that ‘Palestine will be free from the river to the sea’ as antisemitic incidents in a way that we had not traditionally done.”

The post-Oct. 7 turmoil has split both American Jewry and the Democratic Party. The protesters have assailed not just Israeli policy but also Biden’s support for Israel in the Israel-Hamas war. Against that backdrop, there has been much political opportunism.

In March, when Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., the majority leader and the nation’s highest-ranking Jewish elected official, called for new elections to replace Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, congressional Republicans accused him of being anti-Israel. Trump went further, saying that “any Jewish person that votes for Democrats hates their religion.” When Jewish groups criticized his comments, the Trump campaign held firm, saying that the Democratic Party “has turned into a full-blown anti-Israel, antisemitic, pro-terrorist cabal.”

The fissures have opened up on both sides of the aisle.

In a series of hearings since Oct. 7, House Republicans have grilled educational leaders on antisemitism, and last week they introduced a bill to crack down on antisemitic speech on college campuses. While it passed overwhelmingly, with bipartisan support, it gave Republicans a hoped-for opening to press their case that Democrats are soft on antisemitism: Seventy progressive Democrats voted “no,” with some worrying that it would inappropriately inhibit criticism of Israel. But the bill also ended up splitting the right: Twenty-one Republicans voted against it, saying that they feared it would outlaw parts of the Bible.

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., said she would not vote for a bill that “could convict Christians of antisemitism for believing the gospel that says Jesus was handed over to Herod to be crucified by the Jews.” The assertion that Jews were responsible for the killing of Jesus is widely considered an antisemitic trope and has been disavowed by the Roman Catholic Church.

(Evangelical Christians, who have been central to Republicans’ support for Israel, believe that God made an unbreakable promise to Jews designating the region as their homeland. Some also connect Israel’s existence to biblical prophecies about the last days before a theocratic kingdom is established on Earth and, some believe, those who do not convert to Christianity perish.)

In this moment, many Jews in America feel that the most salient threats come from anti-Israel activity, even if in the long term they should not dismiss strains of antisemitism on the “reactionary right” and the “illiberal left,” said Alvin Rosenfeld, director of the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism at Indiana University, Bloomington.

“If you were to ask me, where do I think the most serious threats today come from,” he said, “it wouldn’t be first and foremost from some things that politicians have said.”

But as America’s presidential election draws nearer, he cautioned, that might change.

“It’s turning very ugly,” he said, adding that Trump’s comments about Jews who vote for Democrats “go beyond what I could have imagined, even. It’s not just bad, it’s vile.”

Targeting Soros

Trump once claimed to be “the least antisemitic person that you’ve ever seen in your entire life,” but he has a history of trafficking in antisemitic tropes.

During the 2016 campaign, he tweeted a photo of Hillary Clinton against a backdrop of $100 bills and a Star of David. His closing campaign ad featured Soros — along with Janet Yellen, then chair of the Federal Reserve, and Lloyd Blankfein, then the CEO of Goldman Sachs, both of whom are Jewish — as examples of “global special interests” enriching themselves on the backs of working Americans.

In 2018, he helped popularize the unfounded conspiracy theory that Soros was financing a caravan of Central American migrants, a view shared by the gunman who killed 11 congregants at a Pittsburgh synagogue.

Trump’s targeting of Soros escalated in the run-up to his indictment last April in New York on charges related to hush-money payments to a porn actor who claimed they had had a sexual encounter. Trump said Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg had been “handpicked and funded by George Soros,” an allegation then amplified by Trump acolytes.

In fact, Soros’ involvement was indirect: In 2021, the political arm of a racial-justice organization called Color of Change pledged $1 million to the Bragg campaign; shortly afterward, the group received $1 million from Soros, one of several donations, totaling about $4 million, since 2016. Color of Change eventually spent about $425,000 in support of Bragg; a spokesperson for Soros said none of his contributions had been earmarked for the candidate.

Since then, Trump’s attacks have only intensified and widened — blaming Soros or globalists, for example, for letting “violent criminals” go free, “buying the White House” and turning America into a “Marxist Third World nation.”

In Congress, Republican lawmakers who followed Trump’s lead run the gamut, from conspiracy theorists like Greene and Paul Gosar of Arizona to party leaders like Elise Stefanik of New York, the No. 4 House Republican, and Johnson.

On several occasions, Johnson has criticized the Manhattan district attorney prosecuting Trump by prominently referring to his indirect links to Soros. Last spring, in a newsletter to constituents, he called Bragg the “Soros-selected DA.”

In a statement for this article, a spokesperson dismissed the idea that Johnson’s references to Soros were antisemitic, pointing to the antisemitism bill introduced last week by Republicans. He added, “No numbers of opinions from so-called ‘experts’ can change the fact that pro-Hamas campus agitators and the DAs who are supposed to prosecute them have both been funded by major Democrat donors including Mr. Soros.”

Greene has been among the most prolific users of the trope. She has invoked Soros or “globalists” at least 120 times over the last five years, including referring to him at least a dozen times during the 2020 election as an “enemy of the people,” an epithet used by Nazis and Stalinists that Trump has wielded against journalists and other perceived opponents. She did not respond to a request for comment.

Code Words

Across the centuries, the conspiracy theory of the manipulative, avaricious Jew has worn many faces, from Judas to Shylock to the Rothschilds. Under Stalin, accusations of “rootless cosmopolitanism” echoed Adolf Hitler’s charges about a “poison injected by the international and cosmopolitan Jew(s),” to destroy the Aryan race.

After the Cold War, the code words “internationalist” and “cosmopolitan” were largely replaced by “globalist” and “Soros,” according to Pamela Nadell, a professor of history and Jewish studies at American University. Soros became a target of Hungary’s right-wing nationalist prime minister, Viktor Orban, who is something of a hero on the American right.

An analysis of right-wing extremist media in the United States — including neo-Nazi sites like The Daily Stormer and an ADL database of the transcripts of more than 50,000 episodes of extremist and conspiracy-oriented podcasts — revealed a flood of bluntly antisemitic iterations of the globalist and Soros tropes.

In a June 2022 podcast, for example, Harry Vox, a self-described investigative journalist, railed against “every scumbag who uses the word ‘globalist’ because he’s afraid to use ‘Jewish banking cartel,’ which is the real definition for the term ‘globalist.’”

While people like Vox operate largely out of sight of mainstream politics, some purveyors of blatantly antisemitic rhetoric have become woven into Trump’s Republican Party.

Greene and Gaetz have appeared on the “Infowars” program hosted by Alex Jones, who said in 2017 that “the head of the Jewish mafia is George Soros.” Jones was an early supporter of Trump, who appeared on “Infowars” during his first presidential campaign. During a 2022 episode, Jones said, “I understand there’s a Jewish mafia, and they’re used to demonize anybody that promotes freedom, but I don’t blame Jews in general for that.” His guest on that episode was rapper Kanye West — now known as Ye — who professed admiration for Hitler.

In late 2022, Trump hosted West at dinner at Mar-a-Lago along with Nick Fuentes, the white nationalist leader and outspoken Holocaust denier. In the ensuing publicity firestorm, Trump said in a statement that he did not know Fuentes, and that West “expressed no anti-Semitism, & I appreciated all of the nice things he said about me on ‘Tucker Carlson.’”

Last May, Trump phoned in to an event at his Miami resort hosted by the ReAwaken America Tour, a Christian nationalist road show featuring speakers who have promoted far-right, often antisemitic, conspiracy theories. The tour has been led in part by Michael Flynn, Trump’s former national security adviser, who said during a ReAwaken rally in 2021 that the United States should have only one religion. Trump praised the May attendees for being a part of an “important purpose,” and said he wanted to bring Flynn back to the White House. Trump’s eldest sons, and others from his inner circle, have been featured speakers on the tour.

The current climate has highlighted Republican politicians’ split-screen messaging.

After Oct. 7, Rep. Andy Biggs, R-Ariz., posted on the social platform X, “Anti-Semitism and calls for the destruction of Israel are detrimental to the safety of our Jewish communities.” Just months before, he had appeared on a show hosted by Stew Peters, a conspiracy theorist who promotes antisemitic tropes including that “the criminal cabal — primarily Jewish-controlled central banks” are funding evil in America. At least three other congressional Republicans have appeared on Peters’ show.

Recently some Republicans have blamed Soros for the pro-Palestinian protests. “America-hating, chaos-funding George Soros at work again trying to destabilize our nation on behalf of Hamas terrorists,” Rep. Beth Van Duyne, R-Texas, wrote on X.

In fact, Soros’ connection to the protests is indirect: His foundation has donated to groups that have supported pro-Palestinian efforts, including recent protests, according to its financial records. It has also given to groups that focus on fighting antisemitism, the records show. “We have never and will never pay protesters, nor do we coordinate, train, or advise participants or grantees on the advocacy tactics they choose to pursue,” said a spokesperson for the foundation.

Asked by the Times whether she was aware that the invocations of Soros are widely considered anti-Jewish in certain contexts, Van Duyne posted the questions and her response on X. In addition to funding “organizations that are driving antisemitism on college campuses,” she wrote, “Soros also funded the violent BLM movement, organizations who fought to defund the police, and helped elect pro-criminal district attorneys.”

And when conservative movers and shakers gathered in late February for the Conservative Political Action Conference, the annual homecoming of influential activists and politicians on the right, they were greeted this way: “Welcome to CPAC 2024, where globalism goes to die.”

—

Methodology

The Times used a variety of methods to examine the extent to which federal politicians have used language promoting antisemitic tropes. Reporters examined official news releases, congressional newsletters and posts on X (formerly Twitter) of every person who served in Congress over the past 10 years that contained the words “Soros,” “globalist” or “globalism” — terms widely accepted by multiple historians and experts on antisemitism as “dog whistles” that refer to Jews. Reporters read each message to determine if the terms were used in a way that echoed conspiracy theories about Jews. The Times used a similar process to analyze about five years of campaign emails from former President Donald Trump. The Times also examined congressional news releases, newsletters and posts on X for words and phrases that experts said could have antisemitic implications when used in conjunction with discussions of Israel. These included “from the river to the sea,” and variants of “colonial,” “Nazi” and “lobby.” Retweets or approving quotes of other messages were counted in the Times analysis, and repeated messages that used the same or very similar language were each tallied separately. Using computer analysis techniques that allow the examination of large amounts of text, the Times also analyzed extremist websites and podcasts to explore how they discussed Soros and globalists. The Anti-Defamation League provided transcripts of extremist and conspiracy-oriented podcasts that frequently mentioned Soros and globalists. Additional sources for congressional newsletters, congressional news releases and emails from the campaign of Trump: DCinbox, LegiStorm, congressional websites, Archive of Political Emails.

c.2024 The New York Times Company