Renovations to Selma center bring back memories of Bloody Sunday

Helen Brooks and Alice Moore did not know each other when they marched for voting rights on Bloody Sunday in 1965.

But both girls, then 13 and 16 respectively, ran with their sisters to the river under the Edmond Pettus Bridge to quell their burning faces after state troopers fired tear gas into the crowd.

More: Previous Coverage Selma center that chronicles civil rights march is getting a $20M upgrade

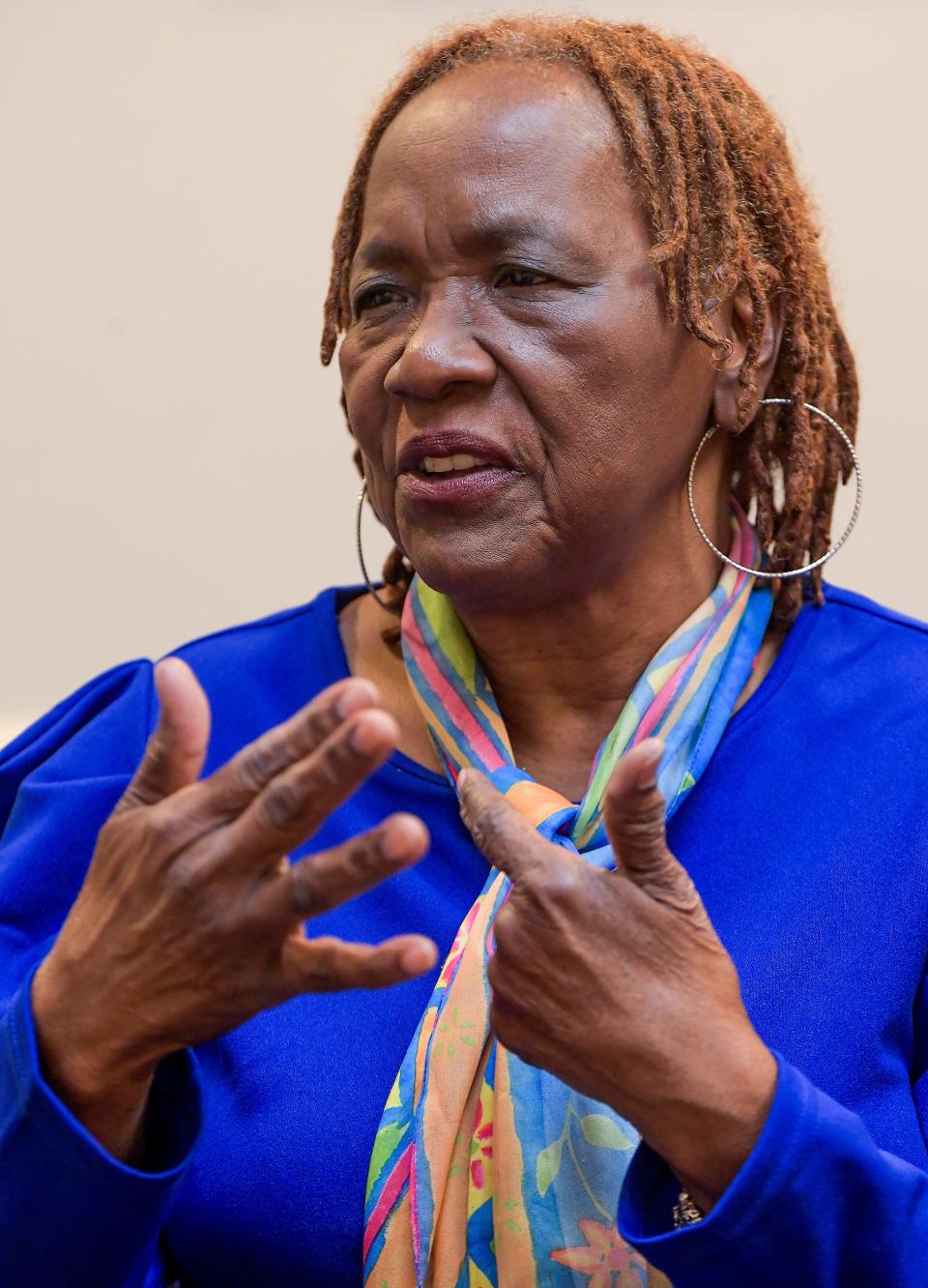

“Nobody can prepare you for it when you’re getting a straight shot of tear gas in your face," Moore said.

Moore said she “just laid there until I could recover myself, until I could see."

They did not meet each other until nearly 60 years later, when the National Park Service began collecting oral histories from foot soldiers to incorporate into a renovated Selma Interpretive Center.

Shirley Baxter, the supervisory park ranger for Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, helped collect 199 oral histories from people who participated in the march. Many of the people had never been interviewed before.

Brooks was among those. Her sister Ruby Brooks Lanier, who was also a foot soldier, never got the chance to widely share her experiences. Lanier died in 2014, just months after marching with Brooks on the day's anniversary jubilee.

“I just hate that some people never got the chance to tell their story," Brooks said.

The National Park Service has been collecting these interviews since 2002.

“My goal was to try to find the people who had not been interviewed," Baxter said.

Moving toward the $21 million renovations

At Tabernacle Baptist Church on Tuesday, March 26, more than a dozen people gathered to hear updates on the project. Among them were numerous foot soldiers who stood their ground on the bridge during Bloody Sunday.

The renovations to the Selma Interpretive Center will cost an estimated $21 million, said Barbara Tagger, the acting superintendent for the center.

The plan is for the updates to wrap up by the summer of 2025, said Willie Adams, the trail manager for the Selma-to-Montgomery trail.

But unexpected issues could delay the reopening date, as the park service is renovating another older building and has already come across numerous problems within the building's structure, Adams said.

Tagger will update the plans for the center based on the feedback from the community.

After the bridge

That historic day in 1965 entrenched the Edmund Pettus Bridge as a symbol of the voting rights movement, and its image summons a different memory for all of the 199 people who shared their stories.

Brooks remembers holding hands with Lanier, as they knelt down to pray all those years ago on Bloody Sunday.

While they were on their knees, the state troopers began to charge them, hurling tear gas at the group of mostly teens.

That's when a crowd, including Brooks and Moore, ran to the river. The two girls were just a few feet away from one another, but after that moment, their paths diverged.

Moore was not scared. She credits that to her youth.

“We were ready to go back after Bloody Sunday," Moore said.

Neither girl was arrested on Bloody Sunday, although both were arrested several times during other protests.

In 1967, the school district asked for volunteers to help integrate the white high school. Brooks stepped up along with five other Black students.

White students harassed Brooks and her Black classmates daily. They yelled slurs. They followed them in their cars as they walked home from school.

Brooks could not focus in class. She could not study. She was afraid.

A month before Brooks was set to re-enroll at the Black school, a boy spit on her. Brooks said she forgot all about her non-violence training and spat back. It was then that she made up her mind to leave Selma.

So she did.

“I just didn’t want to stay in a place where I was constantly rejected," Brooks said.

In 1970, Brooks moved to New York City to attend Brooklyn College. She began a career in social work and stayed until 1993, when she arrived back in Selma.

“No matter where you go, I was like this when I was in New York, Selma will always be my home," Brooks said.

When she moved home, Brooks was struck by the fact that Joseph Smitherman, the man who had been mayor in 1965, still held the position. After retiring, Brooks eventually moved near Savannah, Georgia, to live close to her daughters.

Moore also eventually left Selma, moving to Atlanta. Her youthful fearlessness eventually left, too. The trauma from the events of her teenage years crept in.

“It began to resonate to me as an older person because I would weep a lot. I would cry a lot as I think about it but that came with age," Moore said. She later added, “because I didn’t talk about it. I didn’t talk about it to other people."

Returning to Selma

In 2015, Moore stepped across the bridge for the first time since Bloody Sunday during a reenactment of the event.

“It was very unnerving," she said. "I made it across, and I didn’t walk back across."

After Bloody Sunday, Moore said she learned to use her voice in other ways. She writes letters to legislators and attends political events.

When Ahmaud Arbery was slain in 2020, Moore took to the streets once more, driving to Brunswick, Georgia, to protest.

Now, when Moore returns to Selma for the jubilee, she is concerned by the lack of care people seem to show for what actually happened on the bridge that day in 1965.

“It was almost a feel(ing) that we forgot why we’re there," Moore said. She later added, “What happened is hardly thought about by those people."

Moore said they do not think about the trauma that she and her companions went through on the Edmond Pettus Bridge. “You don’t get the feeling that anybody really cares about what happened," Moore said. "It’s history, and they come there and take a picture."

This story has been edited to reflect that Alice Moore was arrested prior to Bloody Sunday.

Alex Gladden is the Montgomery Advertiser's public safety reporter. She can be reached at agladden@gannett.com or on Twitter @gladlyalex.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Two women crossed a bridge in 1965. Here they share their experiences