Remember When: Hocking Glass fire fought with only a 'drop of water'

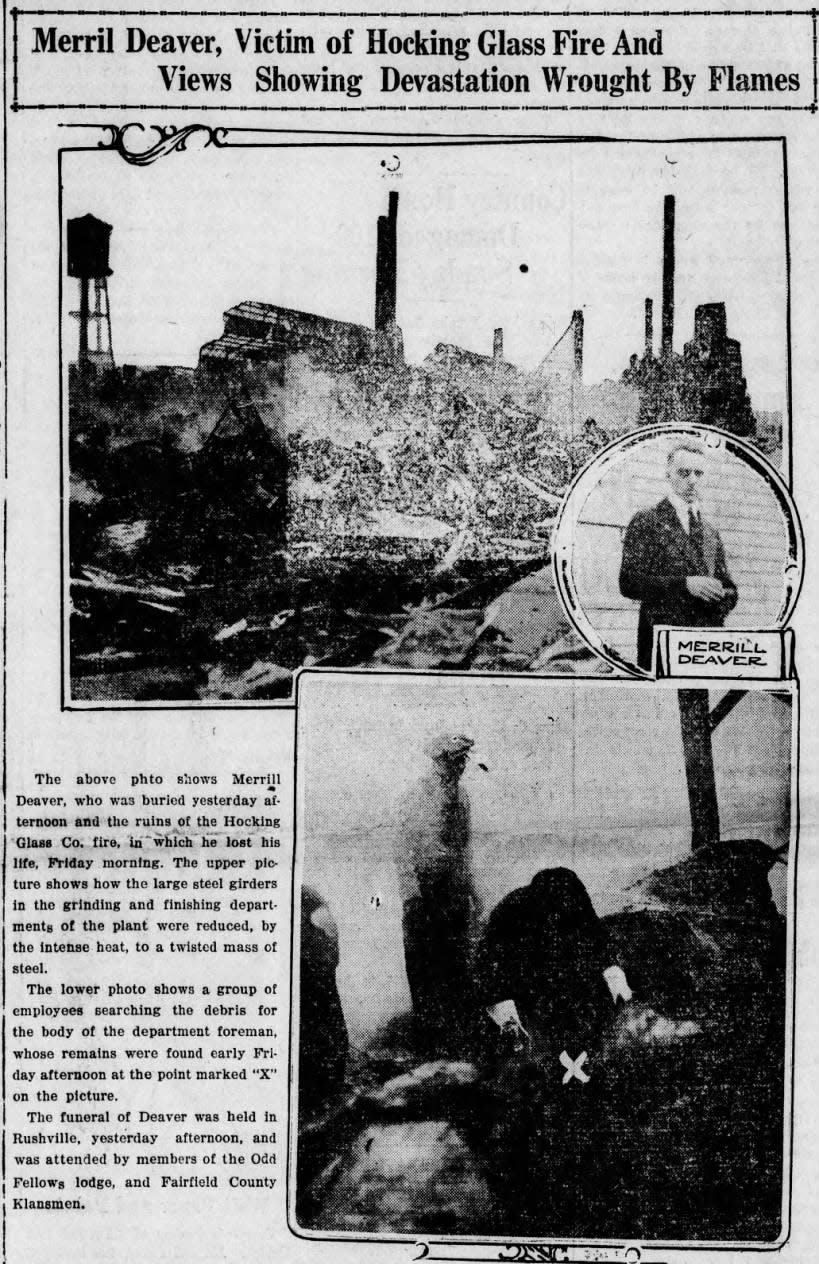

March 7, 1924, the Lancaster Daily Eagle’s front page headline reported: “Million Dollar Fire Destroys Hocking Glass Plant. Body of Merrill Deavers Found in the Ruins.” The date of this horrific event 100 years ago is not one readers would remember without a short review of local history.

Isaac J. Collins first came to Lancaster in 1903 and took a job at the Ohio Flint Glass Co. on Lawrence St. “By 1905, Collins had already been involved with some aspect of the glass business for at least five years, working in two entirely different glass factory operations…he listened and learned. He concluded that a glass factory could make money by supplying the five-and-dime and variety store markets with inexpensive glassware. Volume sales with low markup would generate profit, he believed,” (Mister Collins: Father of Anchor Hocking by Marg Iwen, c2010, p.34).

The former Sutton-Dickey Carbon Co. stood abandoned on the west side of Lancaster, and Collins thought it could become his glass factory. He approached friends and raised enough money to purchase the empty factory and items needed. The Hocking Glass Co. was formally incorporated Nov. 2, 1905, and Collins purchased the glassmaking equipment he needed from the Ohio Flint Glass Co. when it closed Feb. 11, 1906.

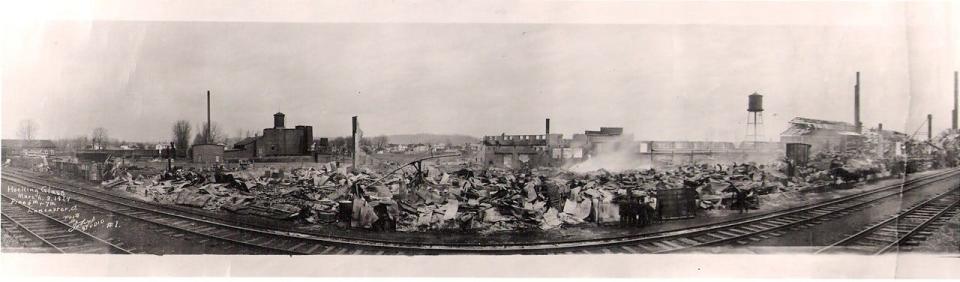

Collins hired Wiliam V. Fisher in 1918 at the end of World War I and in one year Fisher “…had worked himself into the position of general superintendent of the Hocking,” (Iwen, p.51). After these men purchased a rotary pressing machine and a continuous tank to melt glass, “…Hocking’s sales increased from $20,000 during the factory’s first year to $900,000 (more than $12 million in today’s dollars) the same year Fisher was hired,” (Iwen, p.52).Six years later, the Lancaster Daily Eagle’s headline on Friday, March 7, 1924 read: “The most disastrous fire, in the history of Lancaster, destroyed the Hocking Glass Co. factory last night, resulted in a million dollar loss and cost the life of one person. Six hundred and fifty employees were thrown out of work by the catastrophe and local industrial conditions were seriously affected.”

From details published in the Daily Eagle the day after the fire, we learn the fire was discovered on Thursday night, March 6th at 10:45 p.m. by John Schultz, night watchman, in the packing department. He sent an alarm by telephone and fire alarm box. There were 150 people at work that night.

The factory was equipped with an automatic sprinkler system but due to the low pressure of the water supply and a strong wind blowing from the west, the apparatus failed to stop the blaze, which spread rapidly to the decorating and finishing departments. The fire department under the leadership of Chief Landerfelt had arrived by this time with two fire trucks and 2800 feet of hose. They were aided by all the employees in the building who made valiant efforts to stop the fire, but their attempts were futile. The eight inch water main was practically useless, and could only supply a drop in the bucket compared to what was needed.

Lancaster’s Mayor had called the Columbus Fire Chief at midnight. He sent a truck with seven men that arrived at 2 a.m. and did not leave until 5:30 a.m. It was said light from the fire could be seen from Bexley and Logan. Homes surrounding the factory miraculously escaped destruction in spite of the sparks descending over the entire West Side.

At 7:30 a.m. a driving snow storm swept the city and made work more difficult. Louis Noice was in charge of nine men who were appointed to patrol the grounds and prevent spectators from approaching the falling walls, and still flaming wreckage. The largest fire truck returned to the engine house by 4:00 p.m., but the other truck with Chief Landerfelt and several other fire men stayed until about 7:00 p.m. Embers fell around town for some time and everyone was on alert to watch for fires starting up.

Thomas Fulton was the only Hocking Glass official in town the night of the fire. He contacted I. J. Collins who was in Toledo, and E. B. Good in California. These three men owned the company. Fulton also telegraphed cancellations of all orders that had been made by the company. A temporary office was opened in the Wilson Building at the corner of Columbus & Wheeling Sts., and the company’s safe was rescued from the fire.

Bucket brigades were kept busy through the night to help protect homes and companies near the factory. However, “thousands of people” came by foot and in cars to the fire scene and blocked the routes for those fighting the fires. The Herman Tire Building Machine factory was only about 200 feet north of the Hocking fire and was kept under close watch. The Lancaster Leatherboard plant was a short distance away and also in danger.

A very smart and brave Hocking Valley freight train engineer, Steve Oakley, observed the fire as he approached Lancaster. He saw about 25 train cars loaded with new products ready to be shipped. He hooked them onto his train, removed them from the danger of the fire, and saved the factory nearly $100,000.

Sadly, the body of Merrill D. Deavers, an employee of the Hocking Glass Co., was found on Friday afternoon. It was believed Deaver who had recently become a foreman had tried to stay until all his men were out of the fire. It cost him his life. He was 24 years old, and had been married two years. The coroner’s report stated “suffocatoin by smoke.”

Sadly, it took the fire to bring changes. Lancaster’s mayor, service director, and safety director began an investigation of the fire department immediately. The water supply for Hocking Glass had always been short. Collins and Fulton stated they would not reestablish the plant in Lancaster unless a more adequate supply of water and greater fire protection was provided.

March 18, 1924 the Daily Eagle announced the Chamber of Commerce was buying for $20,000 the former Leatherboard factory on the West Side, owned by the Godman Shoe Co. and presenting it as a gift to the Hocking Glass Co. along with three acres and a railroad switch. The Hocking Glass Co.’s attorney stated, “The new factory to be erected soon would exceed the old one in size and would be modern and fireproof.”

Thomas Fulton was able to report (29 March 1924 Daily Eagle) 75 Hocking employees were clearing up wreckage left by the fire, and the Austen Construction Co. was building the new factory with 50 laborers, 20 carpenters and 5 engineers on the job.

“Remarkable return toward normalcy in three months” appeared on the front page of the Daily Eagle May 22, 1924. “Six hundred of the six hundred and fifty workmen employed by the Hocking Glass Co., previous to the fire, are now back on the job.”

Readers may contact Harvey at joycelancastereg@gmail.com

This article originally appeared on Lancaster Eagle-Gazette: Hocking Glass fire fought with only a 'drop of water'