Released from death row, then returned — forced to prove race discrimination a second time

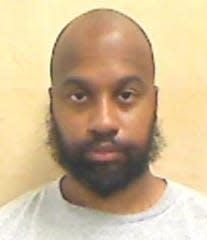

Next week, Tilmon Golphin, a black man who had already proved that his murder trial was tainted by racial discrimination, will be forced to fight for his life before the North Carolina Supreme Court — yet again.

Golphin was just 19 in 1997 when he was charged with capital murder. During jury selection, a black man in the jury pool reported that he overheard two white jurors remarking that Golphin “never should have made it out of the woods” where he and his brother fled.

Instead of the court investigating the reported comments, the prosecutor aggressively questioned the man who reported them, ultimately striking him from the jury. The final selection included only one black person in a county that was likely about 17% African American.

Race-based jury strikes are illegal, but they remain a national problem. In 2012, a trial court reduced Golphin’s sentence from death to life without parole when racial bias was proved in his case (Golphin's brother was 17 and sentenced to life as a juvenile). But that reprieve was short-lived. A year later, legislators repealed the anti-discrimination protections of the Racial Justice Act that saved Golphin and three other people on death row who had also proved discrimination in their capital trials.

All four are back on death row.

For far too long, the nation has lived with the lie that we can construct a legal machinery capable of deciding who lives and dies with fairness and without racism. Golphin's case is the latest in a long line that shows we can't.

North Carolina now has the opportunity to right past wrongs.

Let's stop repeating history

The link between slavery, Jim Crow, lynching and the death penalty is as connected as the intertwined ropes of the lynch-man’s noose.

Two museums bring that point home in stark ways: Alabama's National Memorial for Peace and Justice forces us to remember the lynchings that took the lives of more than 4,000 African Americans in the seven decades after Reconstruction.

POLICING THE USA: A look at race, justice, media

North Carolina's Levine Museum hosted an exhibit on the legacy of lynching and asked its witnesses to ponder how decades of racial terror still cast a shadow today.

In 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court ushered in the modern death penalty in the case of Gregg v. Georgia, ruling that capital punishment was “essential.” Without it, the court said, citizens would turn to “self-help, vigilante justice and lynch law.” Essentially, the court charged the criminal justice system with a job once left to mobs with a noose.

I hope North Carolina's Supreme Court will remember that dark history during oral arguments for Golphin and five others, two of whom presented a mountain of evidence yet never got the chance to prove discrimination in their cases before protections were struck down.

Just as African Americans were once disproportionately lynched, they are now disproportionately represented on death row.

Defendants convicted of killing whites are more likely to be sentenced to death than those who kill blacks, and prosecutors routinely exclude black citizens from capital jury service. Forty years after establishing the modern death penalty, we have professionalized and proceduralized the path to execution, but we cannot wash away the stain of racism.

Racial justice

I was proud to be part of the effort in North Carolina — one that should be a model for the nation — to confront the role of race in the death penalty. The Racial Justice Act became law in 2009. It barred execution if a person could show that race was a significant factor in the prosecutor’s decision to seek the death penalty, in the prosecutor’s jury selection, or in the jury’s decision to impose the death sentence.

Death row prisoners from around the state shored up evidence of discrimination in their cases and filed claims. There was plenty of solid evidence: prosecution notes denigrating black jurors whom attorneys attempted to dismiss at trial; training materials designed to help prosecutors dismiss black jurors but evade detections of racism; black citizens excused from jury service for traits deemed acceptable in white citizens; and a comprehensive study showing that prosecutors across North Carolina dismissed black jurors at double the rate of whites.

The same legislature that repealed North Carolina's Racial Justice Act in 2013 also enacted a voter suppression law that a federal court ruled unconstitutional. The federal court stated the law was designed to “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.”

As our state and the nation look on, North Carolina's justices must decide: Will they leave the legacy of lynching firmly in place? Or will they have the moral courage to enforce the constitution so that the sin of racism no longer infects the death penalty?

This decision has national implications.

As the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny."

North Carolina's decision affects us all.

The Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II is the president and senior lecturer of Repairers of the Breach, senior pastor of Greenleaf Christian Church in Goldsboro, North Carolina, former president of the NAACP of North Carolina, and one of the conveners of The National Poor People’s Campaign.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Returned to death row; forced to prove race discrimination second time