Democrats ditch historic U.S. Senate rule blamed for gridlock

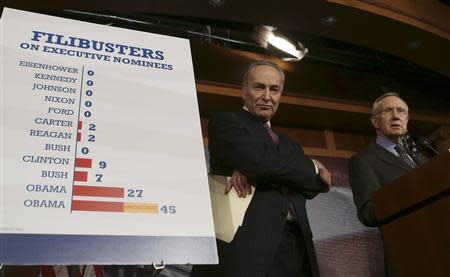

By Thomas Ferraro and Richard Cowan WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The Democratic-controlled U.S. Senate, in a historic and bitterly fought rule change, stripped Republicans on Thursday of their ability to block President Barack Obama's judicial and executive branch nominees. The action fundamentally altered the way Congress' upper chamber has worked since the mid-19th century by making it impossible for a minority party, on its own, to block presidential appointments, except those to the U.S. Supreme Court. The change in the so-called "filibuster" rule does not apply to legislation, which can still be held up by a handful of senators. The now-defunct rule, a symbol of Washington gridlock, has survived dozens of attacks over the years largely because both major political parties like to use it. The action will undoubtedly come back to haunt Democrats the next time they lose the Senate and the White House simultaneously. Getting rid of it was considered so momentous and divisive that it was dubbed the "nuclear option" in the Senate. On a nearly party-line vote of 52-48, the Senate reduced from 60 to 51 the number of votes needed to end procedural roadblocks. Obama, a former senator, praised the action, calling the filibuster "a reckless and relentless tool to grind all business to a halt." The change will speed up the confirmation of Obama appointments to the courts as well as to cabinet and regulatory agencies. One beneficiary is likely to be Representative Mel Watt, whose nomination to take over the agency that regulates mortgage finance giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was being blocked by Republicans. But the immediate spark was Democratic frustration at Republican use of the filibuster to block Obama's appointments to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, considered the nation's second most important court after the U.S. Supreme Court. The Washington-based appeals court handles crucial disputes over the powers of the presidency and Congress, along with regulatory matters involving air and water pollution, banks, securities trading, telecommunications and labor relations. It has also been a feeder to the Supreme Court, with four of the current justices being former D.C. Circuit judges. NEW RULE USED QUICKLY Democrats quickly used the new rule by ending a Republican filibuster against one of those court nominees, Patricia Millett, on a vote of 55-43. A vote to confirm her nomination will be held later. Millett is a Harvard-trained lawyer who worked in the administration of both Democratic President Bill Clinton and Republican President George W. Bush. The American Bar Association gave her its top rating for the D.C. Circuit post. As is often the case with stalled nominations, Republicans did not contend that Millet lacked qualifications. They simply do not want to give Obama more appointments to the important court, which they argue is underworked anyway. For nearly two years, Republicans held up confirmation of Richard Cordray as director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau because they objected to the bureau's powers, not to Cordray, who has since been confirmed. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, a Nevada Democrat, led the charge on the rules change, accusing Republicans of record obstructionism and saying the American public is right to believe that "Congress is broken." Reid said that of the 168 filibusters against presidential nominees in U.S. history, half were held against Obama's picks. "It's time to change," Reid said. Republican Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa fired back, "This is a naked power grab." Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell insisted that there was no reason for a rule change, saying Republicans had confirmed the vast majority of Obama's judicial nominees. McConnell also accused Democrats of taking the action merely to divert attention from the botched launch of Obama's healthcare law, known as Obamacare. But with Congress's approval rating in single digits and no indication Republicans will compromise with Obama on much of anything, Reid decided to pull the trigger. Reid assumes that voters, who polls show are disgusted with a largely "do-nothing" Congress, won't be upset by a rule change to confirm stalled nominees, Democratic aides said. Reid also figured that if he did not change the rules, that increasingly anti-compromise Republicans would change them when they win control of the Senate, which could happen in next year's election, the aides said. Stephen Hess, a congressional analyst at The Brookings Institution, said, "There's a good reason why it's called 'the nuclear option.' This does change the system." "And whether it's good or bad depends on from whence you view it and at what moment," Hess said. "It is good for Democrats on the 21st of November, 2013. And it may not be good (for Democrats) if the landscape changes in the mid-term election" next year and Republicans take control of the Senate. Asked whether the Democrats' move could worsen relations with Republicans and make it more difficult to pass legislation, Hess said "I don't know that relations this bad can get an awful lot worse." (Reporting by Thomas Ferraro, Richard Cowan and David Lawder; Editing by Vicki Allen, Fred Barbash and Tim Dobbyn)