Refugee numbers at a 'record high' — here's how to fix that

The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) released its Global Trends report on the global refugee crisis on Tuesday, concluding that the world's forcibly displaced population was at a "record high."

According to the report, a total of 68.5 million people were displaced by the end of 2017, increased by 2.9 million since 2016. During 2017 alone, 16.2 million people fled — which comes out to 44,500 people becoming refugees every day of last year. This is the largest increase of refugees UNHCR has seen in a single year.

SEE ALSO: 7 activist groups supporting families at the border that need your help right now

To put it into perspective, it means one out of every 110 people has been forced to flee their homes, and someone is forced to leave every 2 seconds.

In a press briefing, UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi noted that 85 percent of the 68.5 million displaced people fled to "poor or middle income countries." He dispelled the myth that the refugee crisis is a "crisis of the rich world."

"It is not," Grandi said. "It continues to be a crisis mostly of the poor world."

Image: united nations refugee agency

Where the forcibly displaced are coming from

Global Trends puts forcibly displaced people into three main categories: refugees, internally displaced people (IDP), and asylum-seekers. These people fled their homes "as a result of persecution, conflict, or generalized violence."

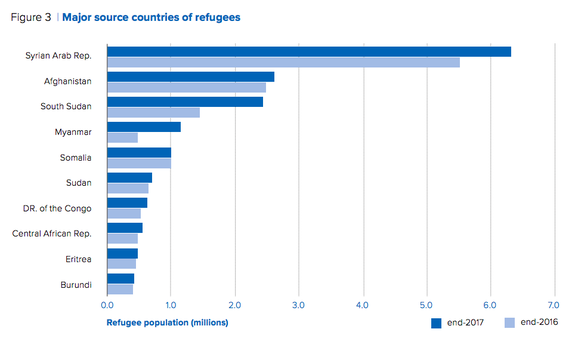

Refugees

Refugees are defined as someone who "has been forced to flee" because of "persecution, war, or violence." There were 25.4 million refugees as of 2017. Sixty eight percent of the total refugees fled from five countries: Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, and Somalia.

Image: united nations refugee agency

Global Trends highlights the conflict Rohingya Muslims face. They have fled Myanmar for years, but a new wave of displacement was triggered by an outbreak of violence in August 2017. Approximately 1 million Rohingya have lived in Myanmar's Rakhine State for generations, but have been barred from citizenship because Myanmar's laws grant citizenship based on ethnicity. Because they are stateless, the Rohingya have been subjected to discrimination and denied basic human rights.

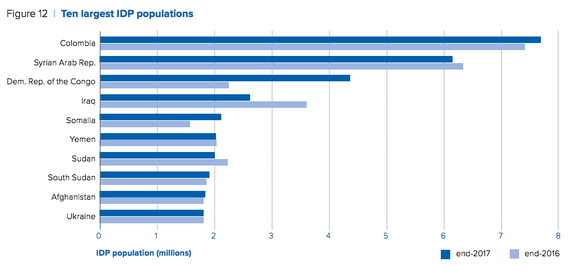

Internally displaced people (IDPs)

By the end of 2017, an estimated 40 million people fled to different parts of their own countries because of armed conflict, generalized violence, or human rights violations. Columbia had the largest population of IDP, with Syria second, and the Democratic Republic of Congo third.

Image: united nations refugee agency

Global Trends spotlighted the Democratic Republic of Congo's IDP population, noting that the number of IDPs doubled from 2.2 million to 4.4 million in just one year. In addition to facing conflict within its own country, the DRC also hosted more than 500,000 refugees from other countries.

Asylum-seekers

UNHCR defines asylum-seekers as someone "whose request for sanctuary has yet to be processed."

The United States took in the highest number of asylum-seekers since 2012, with 331,700 people accepted. Forty three percent of applicants were from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Germany, on the other hand, saw a sharp 73 percent decline in total applications. A majority of claims were from Syrians. Italy accepted the third largest number of claims, a majority of which were from Nigerians.

Why the numbers are going up

Grandi attributed the increase to lack of "significant progress in peace building," particularly in each country's leadership.

He emphasized the conflict in South Sudan, where the political process seems to be at a standstill: "I don't think the leadership of South Sudan and the opposition are taking seriously the desperate situation of their own people, in spite of the pressures."

Grandi also stressed the fragility and lack of stability in the home countries of many refugees. In Yemen, for example, the closure of ports has led to a strain on humanitarian efforts and trade. And in Syria, which Grandi says is politically "stuck," ISIS is still a threat.

What we can do

The report outlines three options for the crisis: returns, resettlement, and local integration.

Returning to their home country is usually the preferred solution for many refugees. But returning in "voluntary, safe, and dignified" conditions is difficult — in Nigeria, for example, 150,000 refugees returned from Cameroon but UNHCR expressed concerns over whether the people returning had done so of their own free will.

The second option UNHCR offers is resettlement. According to the report, resettlement is a "tangible way to achieve enhanced solidarity and responsibility-sharing." Although an increased number of countries showed interest in establishing or maintaining resettlement programs, there was a significant decline in global resettlement opportunities in 2017. As a result, UNHCR submitted 54 percent less refugees for resettlement — from 163,200 in 2016 to 75,200 in 2017.

Global Trends calls quantifying local integration "challenging" because there are so many factors involved. Under local integration, a refugee would find a permanent home in their asylum country, pursue careers, and over time, potentially apply for citizenship. But it's a deeply complex process given the legal roadblocks many refugees face.

Ultimately, as Grandi said, the solutions UNHCR offers are impossible without the cooperation of local governments.

"In the end it's political action that has to occur for the root causes to be addressed," he said.