Referendum games: The people have spoken, but the legislators have the final say

By a margin of roughly 53-47, or about 58,000 votes, the citizens of Utah approved a ballot measure last month to legalize medical marijuana, allowing doctors to prescribe, and dispensaries to distribute, the drug for specified conditions.

Anyway, they thought that’s what they were doing. But within 27 days of passing, Proposition 2 was overturned in a special session of the state Legislature and replaced by the Utah Medical Cannabis Act, which does the same thing but under much more restrictive terms. Among other changes, the law requires that marijuana be dispensed by a licensed pharmacist and narrows the list of conditions for which it is authorized.

The referendum is, in theory, the purest expression of democracy: Voters get a direct say on the law, bypassing the cumbersome legislative process. But in Utah and many of the other 26 states and the District of Columbia whose constitutions allow for ballot initiatives, it comes with a hitch: Legislators can preempt, change or even overturn ballot initiatives approved at the polls.

Legalizing marijuana, even for medical uses, was always going to be a hard sell in Utah, whose politics are heavily influenced by its large Mormon population. In August, when the church — whose tenets ban the consumption of alcohol and even caffeine — announced its opposition, it seemed as if Proposition 2 was probably doomed. Instead, though, proponents and opponents in the legislature hammered out the compromise measure that became the Medical Cannabis Act, and pledged they would support it whether the ballot initiative passed or failed.

That’s legal under the Utah Constitution, but it raises a question: Why bother holding a referendum on the measure at all, if the legislature could decide the issue on its own?

Matthew Schweich, the deputy director of the Marijuana Policy Project, worked on the Proposition 2 campaign and told Yahoo News the deal was unique in his experience of working on ballot initiatives but a step forward for the cause. A pair of advocacy groups sued last week to stifle the new law and reinstitute the language of Proposition 2, stating that the Mormon church violated state law by attempting to influence the election. Schweich said that other organizers have shared frustration with the pared-down law but that the compromise was the best deal supporters could get at this time.

“I respect where they’re coming from and I understand why they think this deal was wrong, but when I look at all the facts, including the internal polling, I was certain that this was the right thing to do,” said Schweich. “It’s not about winning ballot initiatives and getting a notch on your belt, it’s about delivering a public policy outcome for the people that need it. In this case, those people were Utah medical marijuana patients. If we had rolled the dice and we had not made the deal and we had lost Prop 2, medical marijuana patients would have been left with absolutely nothing, and that was an outcome we would not tolerate.”

Michigan is another state where the Legislature can override the results of a referendum, although it requires a three-quarters supermajority to do it. There’s a catch, though: If an initiative petition gathers enough signatures to go on the ballot, legislators can preempt the public vote and pass the measure directly — in which case it is treated like an ordinary bill, which can be rescinded or amended by a simple majority. And lo and behold, in September, with urging from the business community, the Republican-controlled Michigan Legislature passed minimum- and tipped-wage hikes in addition to paid sick leave before they could go to the ballot. The initiatives would likely have passed, in a year in which Michigan voters elected a Democratic governor and passed progressive initiatives to legalize marijuana, eliminate gerrymandering and expand voters’ rights. Minimum-wage-hike ballot initiatives also won in Missouri and Arkansas, states considered far more conservative than Michigan.

If the measures had been approved by the voters in a referendum, the three-quarters threshold to change them in the Legislature would have been in effect. Instead, a few weeks after the midterm elections, the Michigan Legislature did exactly what supporters had feared and gutted the labor-friendly bills at the behest of local business groups. Those in favor of the minimum-wage hikes and paid-sick-leave campaigns vowed to sue and stated that the Legislature had subverted the will of voters by not allowing the initiatives to reach the ballot.

“Most of the [senators] that are hearing these [bills] have been voted out or are term-limited,” said Danielle Atkinson, one of the organizers of the MI Time to Care ballot committee, which backed the sick-leave initiative, in an interview with Bridge magazine. “They’re not going to have to live with the consequences of their constituents telling them that this is bad.”

“It’s a broken system,” Atkinson added, “and we really need to have a process that lets people put their input in. And we also need representatives and senators that respect the ballot initiative process enough not to gut a bill that they passed a few months ago.”

Outgoing Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican, has yet to sign the bills. If he doesn’t sign them, they would need to be voted on again next year under new Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

But it’s not just Republican-led legislatures overturning ballot initiatives. In June, residents of Washington, D.C., voted to eliminate the tipped minimum wage, gradually phasing it out through 2025. Initiative 77 passed with 55 percent of the vote, but after lobbying from the city’s restaurant industry, the predominantly Democratic City Council voted in October to overturn the measure by a vote of 8-5, calling it a “bad law” that would hurt the city’s dining scene.

It’s the fifth time the D.C. Council has overturned a voter initiative, most recently in 2001 when it eliminated term limits on local politicians. Congress also has the ability to overturn laws in the district, which does not have voting representation in the body. Supporters of Initiative 77 are attempting to gain enough signatures to trigger a special referendum to repeal the Council’s repeal.

In Maine, it was the governor who stopped the implementation of Medicaid expansion via ballot referendum. The measure passed in November 2017 with 58 percent of the vote, but Republican Gov. Paul LePage denied 70,000 low-income adults access to health care, stating that it wasn’t funded.

“I will go to jail before I put the state in red ink,” said LePage in a July radio interview. “And if the court tells me I have to do it, then we’re going to be going to jail.”

The matter went to courts but will be resolved in January when Gov.-elect Janet Mills, a Democrat, takes office. Mills, the state’s attorney general, campaigned on seeing through the expansion, and it’s expected to be one of her first acts as chief executive.

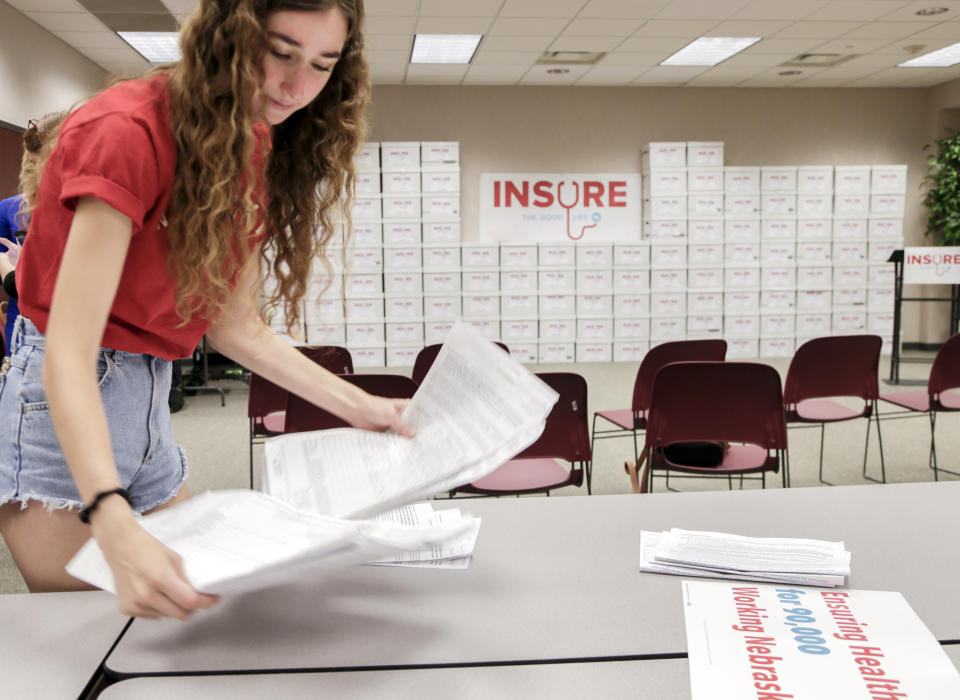

Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, a Republican, said he would not raise taxes in order to pay for the Medicaid expansion passed last month by voters there. Ricketts told the Associated Press that the money could come from funding for education or roads.

The courts are also involved with health care expansion in Idaho, where 60 percent of voters said yes on a proposal that would give Medicaid access to tens of thousands of residents. The Idaho Freedom Foundation filed a lawsuit attempting to stop the implementation, stating that it violated the state’s constitution by tying Idaho to potential changes in federal law. The IFF, a libertarian think tank, is being opposed in its suit by the Idaho Medical Association, which represents 3,000 of the state’s doctors, and two moms.

“The whole purpose of our structure of our government is to make sure laws passed by the legislative branch or by the people themselves can be challenged on a constitutional basis in the court system,” said Fred Birnbaum, vice president of the IFF. “There are plenty of examples of laws that have been passed and deem unconstitutional, so this isn’t exactly new ground.”

The Idaho Supreme Court is set to hear the case on Jan. 29.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Cohen is a 'serial liar,' says former Trump aide Lewandowski

Take a number: Migrants, blocked at the border, wait their turn to apply for asylum

An American killing: Why did the U.S. Park Police fatally shoot Bijan Ghaisar?

I called George Bush a ‘wimp’ on the cover of Newsweek. Why I was wrong.

Photos: Manhunt for Strasbourg, France, Christmas market attack suspect