Recovered, but testing positive: Cases aboard Navy carrier raise questions about coronavirus immunity

WASHINGTON — More than a dozen sailors from the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt have tested positive for COVID-19 after they were believed to have recovered, which medical experts say shows how much remains unknown about the virus that causes the disease.

The episode aboard the carrier, which is now back at sea after being sidelined in Guam since late March by a COVID-19 outbreak that infected more than 1,100 members of its roughly 4,900-strong crew, occurred against a backdrop of reports from Germany and South Korea that also found positive test outcomes in previously infected people. The significance of that finding is unclear, according to experts: It most likely reflects the presence of harmless, noninfectious viral particles, but researchers can’t yet rule out the possibility that the patients became reinfected, which would cast doubt on prospects for widespread immunity.

On balance, experts said, the uptick of positive cases on the carrier more likely exposes the limits of testing than it signifies episodes of reinfection. But even that raises a tough question for societies: what to do with people who test positive but probably are not infectious.

A total of 14 Theodore Roosevelt sailors who had appeared to have recovered from the disease have tested positive again, Adm. Michael Gilday, chief of naval operations, told reporters May 21, according to the Washington Post. As with all other sailors who had initially tested positive after the carrier arrived in Guam near the end of March, the crew members had been placed in isolation for 14 days, Cmdr. J. Myers Vasquez, a spokesperson for the U.S. Pacific Fleet, told Yahoo News.

After exhibiting no symptoms for three straight days, each sailor was tested again. If he or she tested negative, then they had to wait another three or four days to be retested. Only if that final test was also negative were they “considered recovered” and allowed out of isolation and back onto the ship, Vasquez said. In practice, this meant sailors who tested positive were in isolation “for almost three weeks,” he added.

Most of the Theodore Roosevelt’s sailors began returning to the carrier on April 29, according to Vasquez. On May 12, a few sailors began to complain of mild body aches and headaches. “They didn’t have the classic respiratory issues or fever” that are more typically associated with COVID-19, Vasquez said.

Officials on the carrier asked the crew whether anyone else was experiencing the same symptoms. “Several others came forward and said, ‘I am,’ and they were tested,” Vasquez said. The sailors who have retested positive are back in isolation on the naval base at Guam, while sailors who were in close contact with them have also been removed from the ship and placed in quarantine, he said.

The Theodore Roosevelt left Guam and entered the Philippine Sea on May 21 to conduct carrier qualification flights for its embarked carrier air wing, according to a Navy announcement. The ship is operating under a new set of measures designed to mitigate the risk of another outbreak, including minimizing in-person meetings, wearing masks and expanding meal hours to enable social distancing.

The phenomenon of patients who appeared to have recovered from COVID-19 testing positive again had also occurred in South Korea, Germany and Singapore, among other countries, according to Dr. Kavita Patel, a former senior health official in the administration of President Barack Obama. But that may be an artifact of the testing.

One of the most common types of test for the coronavirus is a so-called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, which detects the presence of viral RNA, or antigens, in nasal secretions. But in the cases of people who test positive using a PCR test after seeming to recover from the virus, the test may be detecting remnants of the virus that are not infectious, rather than active virus.

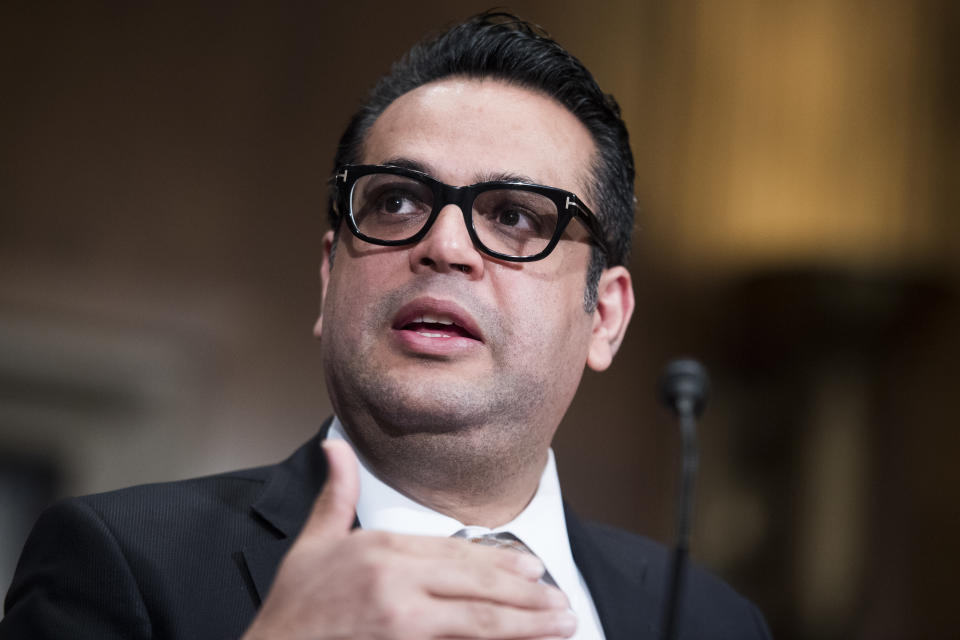

The test “detects the presence of antigens, but it doesn’t necessarily tell you whether it’s live virus or dead virus,” Matthew Donovan, undersecretary of defense for personnel and readiness, told reporters on May 21. “The ones that are retesting positive may actually have those antigens in their blood, but it may be dead virus.” The Defense Health Agency is working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to develop a test “to definitively tell us that the positive is still positive; in other words, they’re still shedding live virus, where they’re infectious,” he said.

In South Korea, “when they went to do a viral culture, to see if those … particles were actually replicating what we would call viral load inside the bloodstream, they did not see that,” Patel said. This is a limitation rather than a failure of the PCR test, which is designed to detect antigens, according to Patel.

A positive PCR test means “they’re shedding virus; they’ve got actual viral particles, but those viral particles might be dormant and not necessarily infectious,” she said. “You would have to culture them to see if they replicate at a certain rate over time and if they could actually pose a threat to the body.”

Another complication is that even though individuals who test positive after recovering may not be infectious, they may still suffer mild symptoms such as those reported by the Theodore Roosevelt crew members, according to Saad Omer, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health.

For patients who do not display the classic COVID-19 symptoms, which usually involve a combination of respiratory problems and a fever, the common nasal swab test is also problematic, according to Patel. “As the virus migrates … into other parts of your body, you might not have a nasal swab that’s always positive, which is why it’s not a perfect test itself,” she said.

The worst-case scenario, both for the Theodore Roosevelt and for society at large, would be if the individuals who tested positive after recovering from COVID-19 had actually been reinfected, because that would not only mean they are capable of infecting others, but it would also imply that recovery from the disease confers little to no immunity against reinfection. In the case of the sailors on the carrier, that possibility is “less likely” because of how soon after testing negative the crew members reported symptoms, Omer said. “The time period is fairly short for it to be the more plausible scenario.”

Patel also sounded an optimistic note about the other reports of COVID-19 survivors who have retested positive. “I haven’t seen global evidence of reinfection,” she said. It might be a plausible explanation in some cases, she added, “but given how infectious this virus is, I would expect there to be more.”

But even if the phenomenon of people testing positive after seeming to recover from COVID-19 can be explained by testing that is either faulty or merely accurately detecting dead virus particles, that in itself can be “controversial,” Patel said, because it raises a tricky question: “What do you do with those people?” In other words, should they be treated the same as any other person testing positive?

Without a deeper understanding of the virus, the Navy’s decision to remove the sailors who had retested positive from the Theodore Roosevelt and place them in isolation again was “the right thing to do,” Patel said. “You don’t want to take the chance.”

But the entire episode “does underscore how much we really have to learn about this virus,” said Samir Deshpande, a spokesperson for the lead Army effort to develop a vaccine for the coronavirus. Patel concurred. “These were tests that were approved within the last 30 to 60 days,” she said. “I don’t think that the same rule of thumb that we’re using for testing today is going to be the paradigm for a year from now, because we’ll just know more about the virus.”

_____

Click here for the latest coronavirus news and updates. According to experts, people over 60 and those who are immunocompromised continue to be the most at risk. If you have questions, please refer to the CDC’s and WHO’s resource guides.

Read more:

Obama says in private call that 'rule of law is at risk' in Michael Flynn case

Yahoo News/YouGov coronavirus poll: Almost 1 in 5 say they won't get vaccinated

Army scientists working on vaccine had long feared emergence of new coronaviruses

Flight attendants see a very different future for airplane travel in the age of coronavirus